by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Derek Neal

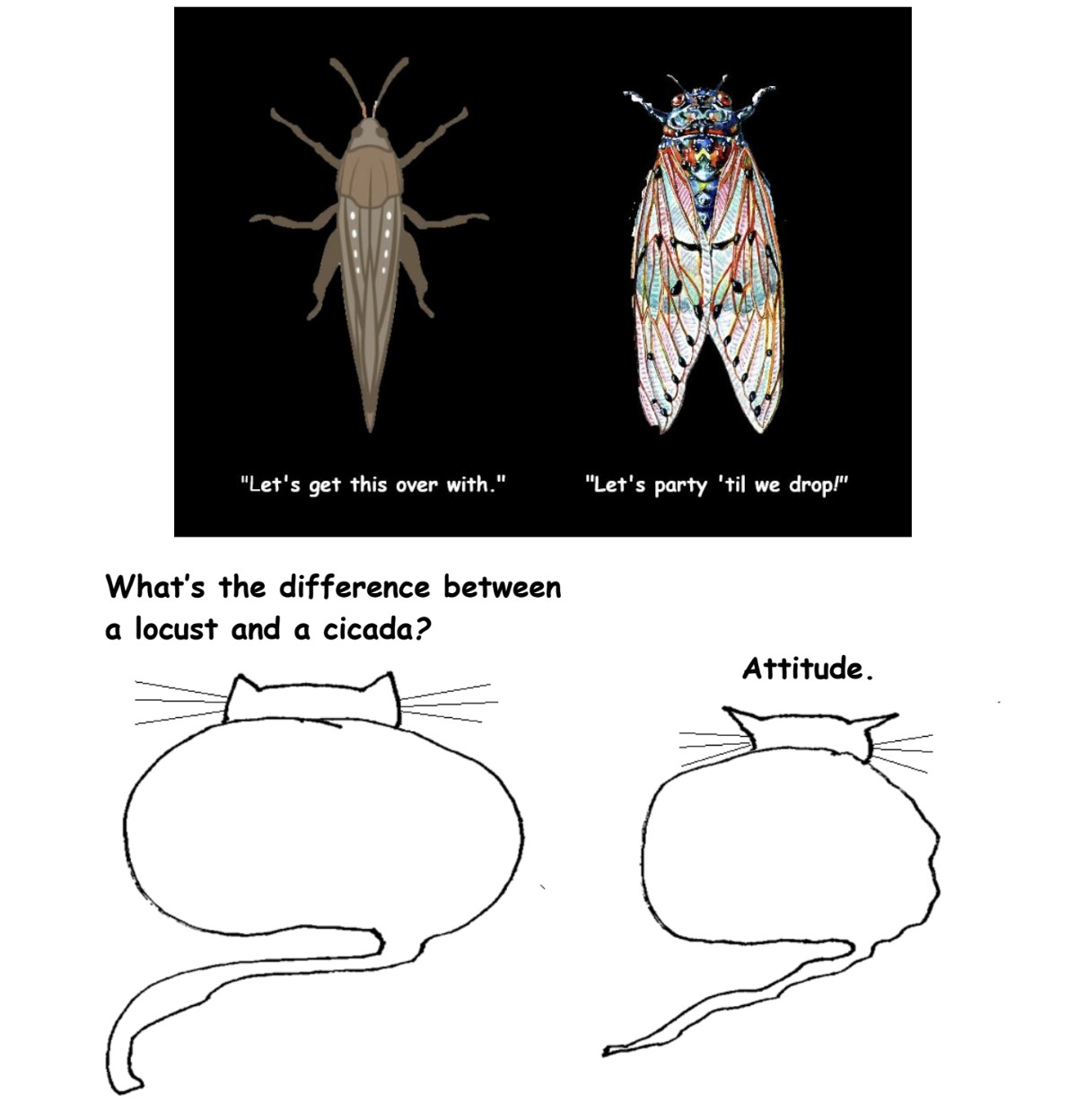

An excerpt of Rachel Cusk’s forthcoming novel, Parade, appeared in the Financial Times last week. The story features two narratives, one about a female painter simply referred to as “G,” told in third person, and another about a group of people visiting a farm in the countryside, told in first person plural. It is unclear how these two stories intersect in terms of plot—is G the narrator of the second story? Is she the woman living on the farm?—but these are not questions worth asking. Thematically, the two stories fit together as they both tell of women constrained and controlled by male figures of authority: in this case, their husbands.

Nestled within this narrative is a fascinating articulation of a theory of art, which is what I will focus on in this essay. Cusk does not pause the story to explain this theory, as some purveyors of “autofiction” might do, but embeds it within the story by explaining G’s different artistic periods and the way her art relates to her personal life. The story is stronger because of this.

In the beginning of G’s career, she is seemingly self-taught, lacking formal and technical skill but compensating for it with inspiration and honesty. Her painting is described as existing “autonomously, living in her like some organism that had happened to make its home there.” In this characterization, G is simply the vessel giving shape to an artistic drive she scarcely understands, rather than the source of its creation. Read more »

by Mike O’Brien

This is going to be a broad-strokes, fast-and-loose affair. Or at least loose. In April I wrote a piece about recent work in the field of animal normativity, a quickly developing area of research that is of interest to me for two key reasons: first, it promises to deepen our knowledge of animal cognition and behaviour, allowing us to better attend to their welfare; second, it promises to fill in the genealogical history of our own normative senses, allowing us to better understand the human experience of morality.

Mostly following the cohort of researchers around Kristin Andrews, who are working on de-anthropocentrized taxonomies and conceptual frameworks for studying animal normativity, I noted that one question of particular interest remains outstanding, viz. “do animals have norms about norms?”. Put another way, do animals think about the (innate, and learned) norms governing life in their communities, and do they (consciously or unconsciously) follow higher-order “meta-normative” rules to resolve conflicts between two or more conflicting norms? The answer still seems to be that they do not, at least not among the higher primates who are the principal focus of study for these questions.

One possible explanation for this apparent absence of recursive or reflexive normativity among non-human animals is a lack of language. It is supposed by some that in order to make norms the object of thought, capable of being analyzed, evaluated, compared and synthesized, some system of external representation is needed, and such a system would fit most definitions of a language. If other species possessed such a powerful cognitive tool, we might suppose that they would use it for all kinds of things, not just resolving normative quandaries. And yet we don’t see much evidence for that kind of abstract, propositional communication among other species. Some tantalizing exceptions come to mind, like enculturated apes using sign language and cetacean communication exhibiting structure and complexity that we have yet to fully understand. But as yet there are no examples of bonobo judges or dolphin sages sorting out the immanent logic of their societies’ rules. Read more »

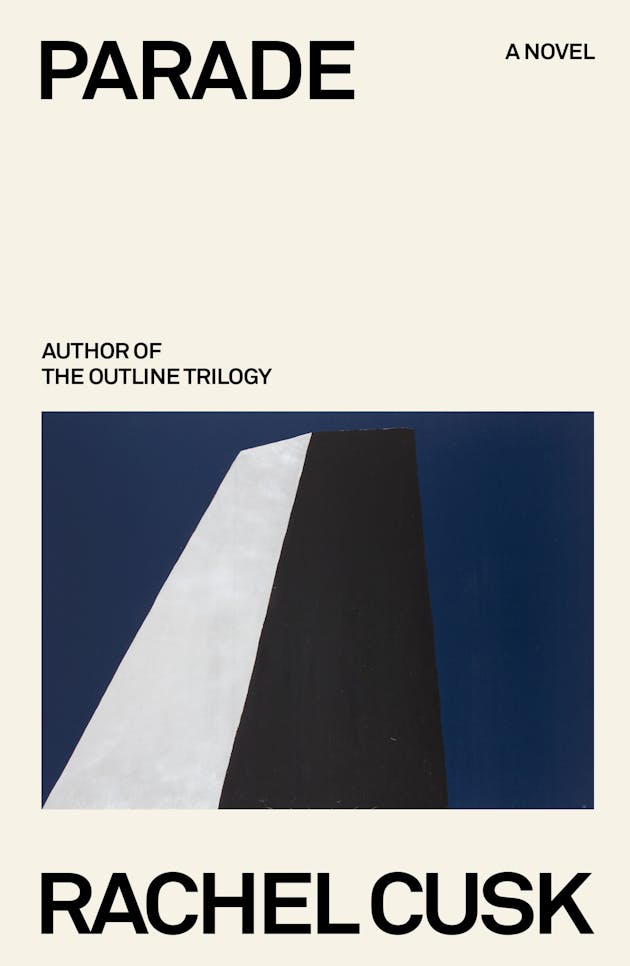

by Michael Liss

The optimistic yet somewhat dyspeptic-looking gentleman to your right (quite appropriately to your right) is Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft, a/k/a “Mr. Republican.” Senator Taft was the son of former President and Chief Justice William Howard Taft, a devoted former member of Herbert Hoover’s staff, and an Isolationist who hinted that FDR had encouraged the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor as a way of inducing America to enter the war against Germany. He was also a fervent proponent of small government and big business, opposed expansion of the New Deal, and in 1947, helped override a Truman veto of the thoroughly anti-Labor Taft-Hartley Act.

In short, Mr. Republican was the real deal. In a 2020 essay for the Heritage Foundation, the conservative historian Lee Edwards wrote:

Before there was Ronald Reagan, there was Barry Goldwater, and before there was Barry Goldwater, there was Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio. From 1938 until his unexpected death in 1953, Taft led the conservative Republican resistance to liberal Democrats and their big-government philosophy.

The man could have been President. He certainly tried—running for the GOP nomination in 1940, 1948, and 1952—and, although he fell short, he inspired a generation of limited-government conservatives and left his name “Taft Republicans” to posterity. Taft, and Taft Republicans, are a starting point for what is called “Movement Conservatism.”

Beginning in the early 1950s, their ideas were adopted, co-opted, and expanded upon, perhaps most notably by the young William F. Buckley, Jr. and his National Review. Buckley and other Movement Conservatives went beyond issues like small government and anti-Communism. They explicitly rejected Abraham Lincoln’s vision that America was “dedicated to the principle that all men are created equal” and instead insisted that the Founders’ core value was the protection of private property. The role of government was to get out of the way—except when advancing the interests of the owners of private property. Read more »

by Jeroen Bouterse

In 2015, political scientist Larry Diamond warned against defeatism in the face of what he called the democratic recession. “It is vital that democrats in the established democracies not lose faith. […] If the current modest recession of democracy spirals into a depression, it will be because those of us in the established democracies were our own worst enemies.” A few years later, as the world’s most powerful democracy had decided to play out that darker option, Diamond wrote with more urgency about how to protect liberal democracy worldwide. In Ill winds, he emphasized the need to provide not only a rejection of alternatives, but a positive vision. “Democracy must demonstrate that it is a just and fair political system that advances humane values and the common good.”

In 2015, political scientist Larry Diamond warned against defeatism in the face of what he called the democratic recession. “It is vital that democrats in the established democracies not lose faith. […] If the current modest recession of democracy spirals into a depression, it will be because those of us in the established democracies were our own worst enemies.” A few years later, as the world’s most powerful democracy had decided to play out that darker option, Diamond wrote with more urgency about how to protect liberal democracy worldwide. In Ill winds, he emphasized the need to provide not only a rejection of alternatives, but a positive vision. “Democracy must demonstrate that it is a just and fair political system that advances humane values and the common good.”

Daniel Chandler places his book Free and Equal (2023) in this same context: for fifteen years in a row, more countries have experienced democratic backsliding than improvement, and the threatened state of democracy worldwide makes it “tempting to go on the defensive”. However, just playing defense is not enough; an ambitious vision for improvement is necessary. “In a moment that calls for creativity and boldness, all too often we find timidity or, worse, scepticism and cynicism”. Chandler believes he has found a recipe for combining the values of liberalism with the spirit of progress and reform.

This combination is crucial. One of the most dangerous narratives taking root in the collective subconscious is that liberalism has had its day; that history is moving on, that liberal democracy belonged to a geopolitical era that is coming to an end, something we tried and that we know the limits of; a system that has already given all it will ever be able to give. Well, not if Chandler has anything to say about it. “There are plenty of exciting and workable ideas about how we could do things differently”, he announces. As our guide to these ideas he has selected John Rawls, and this is quite plainly an excellent decision: Rawls is at the center of 20th-century liberal political thought, but also utopian and principled to an extent that he can hardly be accused of rationalizing an already-existing situation. It makes complete sense to use him as a rallying point for a forward-looking form of liberalism. Read more »

Every book just speaks,

and every light just shines,

and every touch just feels,

and every look just finds,

and everywhere just is,

and every road’s a line —

So, throw your bread on the water

and beat your feet to the chimes

and if you have a daughter

and count your change to the dime

and if you open up the borders, you’ll

let it all fall in behind—

When every deed is done

and you might be feeling so low,

as if a dream is over,

as if it didn’t grow,

you know the soil is still good

and with what we know—

Just throw your bread on the water,

and beat your feet to the chimes,

and if you have a daughter,

and count your change to the dime,

and if you open up the borders

it’ll all fall in behind

……………………………………. it’ll

………………… fall in behind—

Jim Culleny, 1970

excerpt from a song

From beginning to end, Unfrosted is constructed with the intricacy of Seinfeld’s stand-up bits. Taken as a sequence of five-minute segments it’s wonderful, and there are resonances among and mid- and long-range connections among those segments. But you can’t carry an hour and 20-minute film on watch-making intricacy alone. There’s got to be a compelling story, a plot. Oh, we’ve got lots of plotting: Kellogg’s vs. Post, Big Milk vs. Big Cereal, Cuban sugar vs. Puerto-Rican sugar, Russia vs. America, mascots vs. Kellogg’s, and all the while NASA’s shooting for the moon. What holds that together? Pop-Tarts

And that’s not enough. As I noted in my original review, “You can’t take a Godzilla toy, hook it up to an air-pump, and expect to inflate it into a world-destroying comedic monster.” Unfrosted in meticulously crafted, but unfocused and rambling.

It’s not enough. Pop-Tarts themselves exist at the right scale for a meticulously-crafted stand-up bit, which is where the movie started, as a stand-up bit. But in a feature-length film Pop-Tarts are reduced to being a MacGuffin. “MacGuffin” is a term of art that means – I’m quoting the dictionary on my computer – “an object or device in a movie or a book that serves merely as a trigger for the plot.” The statue in The Maltese Falcon is a classic example. It turns out to be junk, but it motivates the action.

Let’s take a closer look at Unfrosted. I’m going to start by looking at Seinfeld’s bit about Pop-Tarts, then look at the movie itself, and conclude with some speculative observations about Seinfeld’s aesthetic confusion. Read more »

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Author’s Note: A version of this essay was presented at the London Arts-Based Research Conference (Dec ‘23) on the topic: “The Emergence of Soul: Jung and the Islamic World through Lecture and Art”.

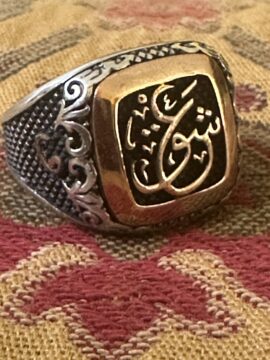

The Sufis aspire to the highest conception of love and understand it to be the vital force within, a metonym for Divine essence itself, obscured by the ego and waiting to be recovered and reclaimed. Sufi poetry, in narrative, or lyric form, involves an earthly lover whose reach for the earthly beloved is not merely a romance, rather, it transcends earthly desire and reveals, as it develops, signs of Divine love, a journey that begins in the heart and involves the physical body, but culminates in the spirit.

The Sufis aspire to the highest conception of love and understand it to be the vital force within, a metonym for Divine essence itself, obscured by the ego and waiting to be recovered and reclaimed. Sufi poetry, in narrative, or lyric form, involves an earthly lover whose reach for the earthly beloved is not merely a romance, rather, it transcends earthly desire and reveals, as it develops, signs of Divine love, a journey that begins in the heart and involves the physical body, but culminates in the spirit.

My reading of Sufi love poetry, translated from different languages, shows that even though this tradition spans more than a millennium and includes disparate cultures, it follows the same mystic logic at its core. Whether folkloric or classical, penned or belonging strictly to the oral tradition, this genre has a discernible sensibility that likely stems from interpretations of the Quran itself.

As I explore the relationship between the earthly and Divine beloved in poetry by Persian, Arabic, Urdu or Punjabi poets, I am led to the love epics sourced from the Quran. These have been abundantly repeated, adapted, and studied, and of course yield a variety of interpretations. I approach them here in relation to the three features that I understand to be the dynamics of Sufi Poetics that integrate the earthly and Divine: An all-encompassing, merciful love as the force of deep awareness (Presence) that facilitates an appreciation of differences and contradictions (Paradox) and pours into harmonious coexistence (Pluralism)— forming a circuit that flows in and out of Divine love. Read more »

by Akim “Scare Quotes Can Indicate Facetiousness” Reinhardt

Two spaces after a period, not one. If a topic sentence leading to a paragraph can get a whole new line and an indentation, then other new sentences can get an extra space. Don’t smush sentences together like puppies in a cardboard box at a WalMart parking lot. Let them breathe. Show them some affection. Teach them to shit outside.

Two spaces after a period, not one. If a topic sentence leading to a paragraph can get a whole new line and an indentation, then other new sentences can get an extra space. Don’t smush sentences together like puppies in a cardboard box at a WalMart parking lot. Let them breathe. Show them some affection. Teach them to shit outside.

Never wear sneakers with a suit. Whenever I see this combo on a man, I silently ask myself, “What exactly is the point of your existence?” Not ours or mine, but yours, personally. Why do you exist and what are you trying to accomplish other than signaling to the world that you’re the snazzy version of a dumb jock on a halftime highlight show? You look like Forrest Gump.

Amid and among instead of amidst and amongst. Amidst and amongst don’t make you sound smart or sophisticated; they make you sound like a boring side character in an unfunny Shakespearean comedy. You’re a modern English speaker, stop trying to sound like you have an Elizabethan speech impediment: Amidst the thorny thistle there, and amongst stones stealthily stored. There’s no shame in talking plainly whilst thou speaketh thy truth.

While sneakers are out, you may wear brown dress shoes with a gray suit. Once upon a time, my dear friend Prachi excoriated me for that combination, insisting a gray suit calls for black shoes. A couple of years later, I noticed her wearing brown dress shoes with a business suit, and eagerly called her on it. She, perhaps not incorrectly, insisted that she looked good in the combo and I don’t. Very well. I will suffer so that the rest of you can be free. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

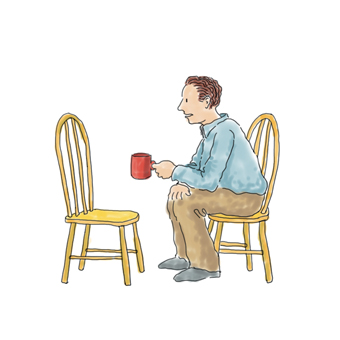

Over thirty years ago I was in an on-again-off-again relationship that I just couldn’t shake. After months of different types of therapies, I lucked into a therapist who walked me through a version of the Gestalt exercise of talking to a chair, which ended my longing for this guy on a dime.

Over thirty years ago I was in an on-again-off-again relationship that I just couldn’t shake. After months of different types of therapies, I lucked into a therapist who walked me through a version of the Gestalt exercise of talking to a chair, which ended my longing for this guy on a dime.

The exercise had me reimagine many ways he had enraged me, bringing all that to the surface. Then it raised any guilt I had around my own actions towards him, sadness around missing him, and finally ended with celebrating what I learned from him. It took just an hour, and I left feeling completely finished, excised of any clinging or craving, and able to effortlessly say “No thanks!” to his next late-night phone calls. Pairing words and actions with emotions in a contained and structured time and space, that gives some order to the chaos, might do next to nothing — but it might help to move through a difficult transition. I was so impressed with this power hour that I went to grad school to study ritual work. Gestalt psychotherapy is a far cry from cultural anthropology, but I perceived a connection to rites of passage that help neophytes transition from one state to another.

I recognize the cringe-factor in all of this, but it’s worked for thousands of years to take children into adulthood, and we’ve kept at it when marrying and burying, so there’s likely something useful in the process. And it feels like we need something transformative more than ever. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Angela Starita

A few months ago, I visited Freehold, NJ, an hour’s drive south of Manhattan. The town has serious Revolutionary War credentials as the site of the Battle of Monmouth, a tactical mixed bag from the American perspective but a definite win for local identity. I grew up in the town just south of Freehold, and the battle, from the annual re-enactment to the many historic plaques and business names in honor of Molly Pitcher, water girl to the Revolution, looms large. As county seat, Freehold is home to the Monmouth County Historical Society and a cache of papers related to a commune once sited in what is today a town called Colts Neck. Named the North American Phalanx (NAP)—mentioned a few months ago in this column—it’s generally viewed by historians as the most successful of a few dozen communes organized around the ideas of one Charles Fourier (1772–1837), a French socialist thinker trying to solve an essential puzzle: how do we pursue our own happiness while working towards communal goals of eradicating poverty, war, and famine? As far as Fourier was concerned, finding a way to get pleasure from work, from camaraderie, from sex, from love is key to ecological and even cosmic progress. Our commitments to capitalism not to mention monogamous family units had obstructed our development as human beings, which, in turn, stymied our physical environments. Most famously, Fourier believed that our oceans would taste of lemonade (what he called a boreal citric acid) once we had freed ourselves of jealousy and greed, and pursued higher forms of knowledge and sensation. But as things stood at the turn of the 19th century, Fourier saw us as mired in pointless, confused pursuits unworthy of our innate talents. As Dominic Pettman put it in a 2019 article for Public Domain Review, Fourier “also took it for granted that aliens on other planets were far more evolved than we are, and that we are the slow kids on the cosmic block, having been mired in incoherency for so long.”

To get us closer to enlightenment as he envisioned it, Fourier proposed a model community to be set up in multiple points around the world. These working, communally-run farms (he called them domestic agricultural associations) would demonstrate the folly of isolated pursuits of consumption, and eventually convert the masses to pursuing their passions in concert with a community. The result would be world-wide harmony, a key term in the Fourier lexicon. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

I was asked recently to speak at the University of Toronto about poetry in translation, a topic close to my heart for a number of reasons. I happened at the time to be working on a text concerned, not with translating poetry, but with lyric expression in its most practical form: that is, as a commodity with a material history, as an object that can be traded, one with an exchange value as well as a use value (however the latter might be defined, or experienced).

I was asked recently to speak at the University of Toronto about poetry in translation, a topic close to my heart for a number of reasons. I happened at the time to be working on a text concerned, not with translating poetry, but with lyric expression in its most practical form: that is, as a commodity with a material history, as an object that can be traded, one with an exchange value as well as a use value (however the latter might be defined, or experienced).

The reason for this pragmatic frame of poetic mind was as follows: I had for pecuniary purposes been learning about fintech (financial technology), about tokenized assets and distributed ledgers, and was thus briefly engaged by an ecosystem distant enough from my typical life experience that it had begun to present itself to me under the lurid aspect of science fiction, as a Peter Max and William S. Burroughs-inspired lucid dream of aliens and teleporting and iridescent currencies riding an ominous conveyor belt of ballot boxes. In other words, my day job was encroaching on my vocation!

The pushback I devised, a method for domesticating this unfamiliar terrain and rendering it at least temporarily welcome, after-hours in my psychological household, was to imagine a range of revered poets—Sappho, Emily Dickinson, John Donne, and Philip Larkin—anachronistically encountering the strange new gods of Bitcoin, Blockchain, and CBDC, and to ghostwrite the appropriate text for each of them. I was so pleased with these efforts that I went on to imagine a newfangled poetry journal featuring videos of poets reading their own work, minted as NFTs or non-fungible tokens—you may know these digital artifacts as the images of a Bored Ape or a Penurious Ex-President—and hosted on a blockchain. I wrote up the concept, and my “white paper” will appear later this year as a contribution to a new Swiss cultural studies journal devoted to the appealingly opaque concept of transindustriality.

And so it was that, when I agreed to give a lecture on translating poetry, I was of a mind to consider that typically immaterial artform as a physical object in circulation, in the process of being fundamentally transformed by the technology of its new medium; and thus it wasn’t a great leap for me to consider the ancient craft of literary translation—think Saint Jerome and his lion—in a thoroughly contemporary form, rather than sub specie aeternitatis. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Once again the world faces death and destruction, and once again it asks questions. The horrific assaults by Hamas on October 7 last year and the widespread bombing by the Israeli government in Gaza raise old questions of morality, law, history and national identity. We have been here before, and if history is any sad reminder, we will undoubtedly be here again. That is all the more reason to grapple with these questions.

Once again the world faces death and destruction, and once again it asks questions. The horrific assaults by Hamas on October 7 last year and the widespread bombing by the Israeli government in Gaza raise old questions of morality, law, history and national identity. We have been here before, and if history is any sad reminder, we will undoubtedly be here again. That is all the more reason to grapple with these questions.

For me, a particularly instructive guide to doing this is Errol Morris’s brilliant 2003 film, “The Fog of War”, that focuses on former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s “eleven lessons” drawn from failures of the United States in the Vietnam War. Probably my favorite documentary of all time, I find both the film and the man fascinating and the lessons timeless. McNamara at 85 is sharp as a tack and appears haunted with the weight of history and his central role in sending 58,000 American soldiers to their deaths in a small, impoverished country far away which was being bombed back into the stone age. Throughout the film he fixes the viewer with an unblinking stare, eyes often tearing up and conviction coming across. McNamara happens to be the only senior government official from any major U.S. war who has taken responsibility for his actions and – what is much more important than offering a simple mea culpa and moving on – gone into great details into the mistakes he and his colleagues made and what future generations can learn from them (in stark contrast, Morris’s similar film about Donald Rumsfeld is infuriating because unlike McNamara, Rumsfeld appears completely self-deluded and totally incapable of introspection).

For me McNamara’s lessons which are drawn from both World War 2 and Vietnam are uncannily applicable to the Israel-Palestine conflict, not so much for any answers they provide but for the soul-searching questions which must be asked. Here are the eleven lessons, and while all are important I will focus on a select few because I believe they are particularly relevant to the present war. Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

One of the great pleasures in life is learning about something today that you couldn’t have imagined yesterday. The infinite richness of mathematics means I get to have this experience regularly. However much I think I know, it is a drop in the ocean of things yet to be learned.

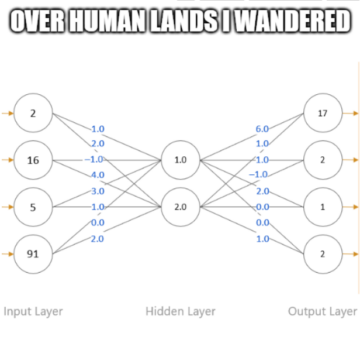

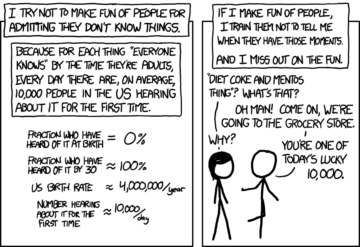

And even if lots of people already know something, it doesn’t matter when it’s new to you. As is often the case, xkcd made this point already. Even the most ordinary facts are amazing and new for the 10,000 or so people learning it today:

A few weeks ago I once again had the joy of learning about a previously hidden corner of the mathematical world: Gaussian Periods. Samantha Platt, a graduate student working with Ellen Eischen at the University of Oregon, gave a fantastic talk about Gaussian Periods in one of our seminars. Since a close second to learning something new is the fun of explaining it to someone else, I thought I’d take this opportunity to share Gaussian Periods with you. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

Here’s the gist of it. I think a recent declaration on animal consciousness, being signed by a growing number of philosophers and scientists, is largely correct about nonhuman animals possessing consciousness, but misleading. It insinuates that animal consciousness is a recent discovery – made in the last five to ten years – based on new experimental work. As exciting and revelatory as recent work on the minds of nonhuman animals is, animal consciousness is hardly a new discovery. In fact, I am not sure the declaration is really a scientific manifesto so much as a moral one. We ought to be treating nonhuman animals better because many seem to have some level of consciousness, but implying we should do so because of new “scientific evidence” may be a mistake.

NBC recently reported that “discoveries…in the last five years” show that a “surprising range of creatures” exhibit “evidence of conscious thought or experience, including insects, fish and some crustaceans.”

“That has prompted a group of top researchers on animal cognition to publish a new pronouncement that they hope will transform how scientists and society view — and care — for animals.”

“Nearly 40 researchers signed The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, which was first presented at a conference at New York University.” Many more have signed the Declaration since then, and many more are likely to sign it in the near future.

Here is The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness in its entirety.

“Which animals have the capacity for conscious experience? While much uncertainty remains, some points of wide agreement have emerged.

First, there is strong scientific support for attributions of conscious experience to other mammals and to birds.

Second, the empirical evidence indicates at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience in all vertebrates (including reptiles, amphibians, and fishes) and many invertebrates (including, at minimum, cephalopod mollusks, decapod crustaceans, and insects).

Third, when there is a realistic possibility of conscious experience in an animal, it is irresponsible to ignore that possibility in decisions affecting that animal. We should consider welfare risks and use the evidence to inform our responses to these risks.”

When I read this my first reaction was “I can’t believe it, they’ve solved the ‘other minds’ problem!” A leading problem in philosophy, after all, has been ‘How do we even know other humans have consciousness?’ – much less nonhuman animals. In fact, one of the signatories to the declaration, leading philosopher of mind David Chalmers, is well-known for arguing that there might be beings (“philosophical zombies”) that look and behave just as we do, but have no consciousness. In other words, recognizing there is a philosophical problem about how we can be justified in attributing consciousness to others. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Light Play in The Living Room, November 2023.

Sughra Raza. Light Play in The Living Room, November 2023.

Digital photograph.

by Brooks Riley

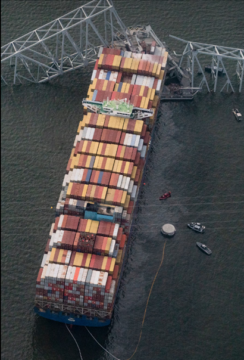

One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

At that hour, long before dawn, it was too dark for the resulting ripple effect to be seen. But it was most certainly a hefty version of the pebble drop, with waves fanning out all the way to the harbor berth from which the Dali had just departed. At daybreak, when images of the disaster began to appear everywhere, the ripples were no longer visible. But given the catastrophic consequences of this event, and the tragic loss of life, they were, and still are, fanning out across the globe.

Am I the only one who can’t stop looking at images of this disaster? Am I the only one who sees an awful beauty in them? Or is it a beautiful awfulness? The frenzy of angles, the implosive intensity of the damage, the jolly Lego-like containers in Bauhaus colors still neatly stacked atop the ship in defiance of the tangled metal of the bridge’s cold steel mesh structure lying over the ship’s forecastle where it fell. Add to that the murky, shifting colors of the water, lending the disaster a visual context like a fluid frame—a calming contrast to the frozen pandemonium it encircles. Read more »