by Michael Liss

Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

—Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, June 6, 1944

We had to storm the beaches at Normandy. There was no other way. None, at least, to loosen Hitler’s death-grip on Western Europe. One by one, proud peoples saw their countries’ armies overwhelmed by Blitzkrieg conducted with a speed and agility that astonished.

First Poland, with Germany’s partner of convenience, the Russians, which then rampaged through Eastern Europe, gobbling up prizes. Then, after a pause for the so-called “Phony War,” the Germans moved on to Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg. May 13, 1940, they pivoted, sent their troops over the River Meuse, blasted and danced past the supposedly impenetrable Maginot Line, and induced the mass evacuation at Dunkirk. The French Army, it could be said the French country, was in full physical and moral retreat. By June 22, it was over. The French were forced into a humiliating armistice in the very railcar in which Germany had accepted defeat in World War I. Hitler literally danced a jig.

Germany occupied roughly three-fifths of European French territory, including the entire coastline across from the English Channel and the Atlantic. Britain had survived the desperate Battle of Britain but stood alone. The Italians joined the Axis to grab some of the spoils for themselves, and, in early 1941, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania followed. In April of that year, the Germans crushed Greece and Yugoslavia.

“Fortress Europe,” essentially a massive buffer zone for the Germans, ending in a fortified Atlantic coastline, became a reality. The Nazis built the Atlantic Wall, a 2,400-mile line of obstacles, including 6.5 million mines, thousands of concrete bunkers and pillboxes bristling with artillery, and countless tank traps. Where there wasn’t a wall, there were cliffs looking over the beaches where Allied forces were expected to land, and, from those cliffs, German soldiers were prepared to rain down fire. Read more »

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude.

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude. Introduction

Introduction LaToya Ruby Frazier. Mom and Mr.Yerby’s hands, 2005.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. Mom and Mr.Yerby’s hands, 2005.

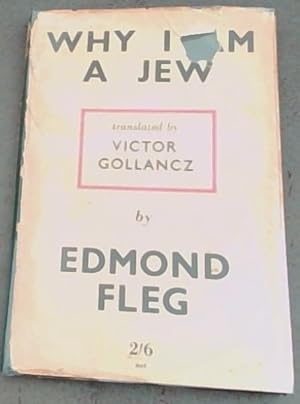

The turn of the 21st century saw a burst of atheistic declarations and critiques in the United States and Great Britain, led by a small group of celebrity atheists including Philosopher Daniel Dennett, Biologist Richard Dawkins, and journalist Christopher Hitchens. I have always found this New Atheism, as the movement is often called, to be a mixed bag. It was long overdue, and many good (if obvious) points were made. However, there was also a fair bit of navel-gazing and even stupidity. And among some of the celebrity leaders, I believe, there was also a profound misunderstanding of religion, how it functions, and even its basic purposes.

The turn of the 21st century saw a burst of atheistic declarations and critiques in the United States and Great Britain, led by a small group of celebrity atheists including Philosopher Daniel Dennett, Biologist Richard Dawkins, and journalist Christopher Hitchens. I have always found this New Atheism, as the movement is often called, to be a mixed bag. It was long overdue, and many good (if obvious) points were made. However, there was also a fair bit of navel-gazing and even stupidity. And among some of the celebrity leaders, I believe, there was also a profound misunderstanding of religion, how it functions, and even its basic purposes.

According to the anthropologist James Bielo

According to the anthropologist James Bielo This is the first in a series of three articles on literature consider as affective technology, affective because it can transform how we feel, technology because it is an art (tekhnē) and, as such, has a logos. In this first article I present the problem, followed by some informal examples, a poem by Coleridge, a passage from Tom Sawyer that echoes passages from my childhood, and some informal comments about underlying mechanism. In the second article I’ll take a close look at a famous Shakespeare sonnet (129) in terms of a model of the reticular activity system first advanced by Warren McCulloch. I’ll take up the problem of coherence of oneself in the third article.

This is the first in a series of three articles on literature consider as affective technology, affective because it can transform how we feel, technology because it is an art (tekhnē) and, as such, has a logos. In this first article I present the problem, followed by some informal examples, a poem by Coleridge, a passage from Tom Sawyer that echoes passages from my childhood, and some informal comments about underlying mechanism. In the second article I’ll take a close look at a famous Shakespeare sonnet (129) in terms of a model of the reticular activity system first advanced by Warren McCulloch. I’ll take up the problem of coherence of oneself in the third article.

Jaffer Kolb. Untitled, June, 2024.

Jaffer Kolb. Untitled, June, 2024.