by Marie Snyder

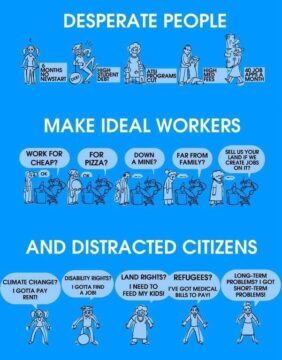

In the West, it feels like we have never lived outside of a system of pseudo-feudalism, a time without peasantry, slavery, or the working poor labouring for the benefit of Kings, land barons, or factory owners. For thousands of years, the exploitation of people appeared necessary to some of the best minds, which shifted as we developed machinery and technology. But now we’re in the realm of drones, 3-D printers, and AI. Once we have the technology that can mine for lithium and coltan at the push of a button, then exploitation of human resources should all but be obliterated, leaving humans to paint and write poetry, right?? Unless, of course, the tactic of keeping people at bare subsistence levels is also a means to control the masses.

In the West, it feels like we have never lived outside of a system of pseudo-feudalism, a time without peasantry, slavery, or the working poor labouring for the benefit of Kings, land barons, or factory owners. For thousands of years, the exploitation of people appeared necessary to some of the best minds, which shifted as we developed machinery and technology. But now we’re in the realm of drones, 3-D printers, and AI. Once we have the technology that can mine for lithium and coltan at the push of a button, then exploitation of human resources should all but be obliterated, leaving humans to paint and write poetry, right?? Unless, of course, the tactic of keeping people at bare subsistence levels is also a means to control the masses.

One perspective of the past thousand years or so might look something like this: Peasants lived on the King’s land, first for free, then later in exchange for a portion of the food they grew or products they crafted. A tax on land started when the Lords realized they could profit more from keeping sheep than people, and peasants had to commodify their labour for the privilege of continuing to live where they had been born. Then we had some revolutions to usher in a whole new way of living, to be able to have individual property rights and to choose our leaders. The wealthy expanded their land into plantations and dragged over people from the colonies to work them in exchange for some food and shelter. It was different in intention than the King/peasant dynamic but not in result: lords allowing food and shelter on their land to people who already lived there in exchange for their labour carries different weight from landowners providing food and shelter to people they kidnapped in exchange for their labour. That type of enforced labour was never abolished, of course; it was merely outsourced to poorer countries and American prisons. More acknowledged today, we have the working poor who make just enough to barely pay for rent and food. Leaving a horrible job at Amazon isn’t a realistic choice without any possibility of saving money. They’re free in title but not in practice. They might very well still live on land belonging to their overlord!

So, when did we have a democracy in which each person’s unmanipulated and unfettered vote counts as much as any other, or human rights in which we all have the right to food and shelter and certain freedoms. Did I blink and miss it? Read more »

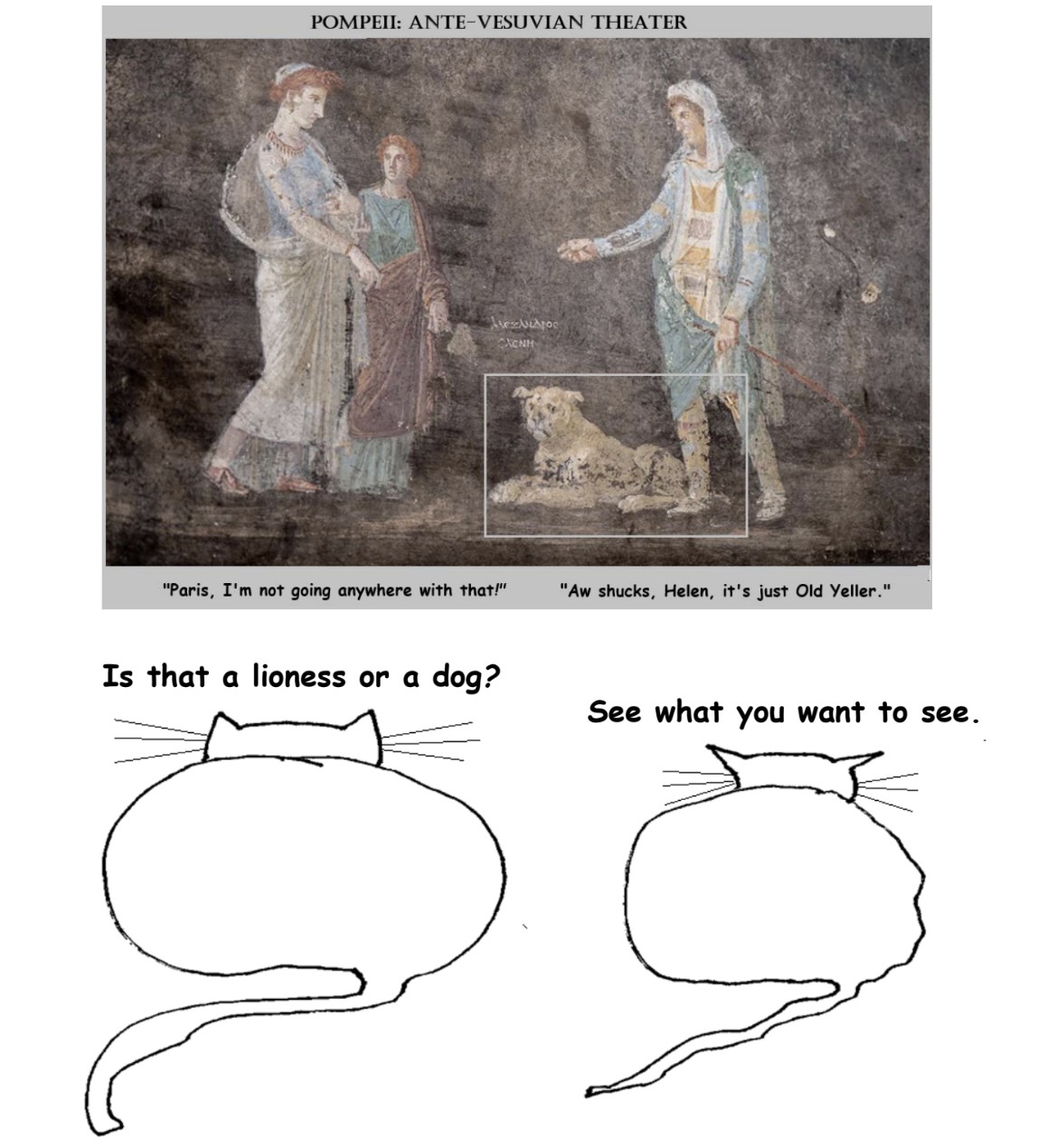

If 1840 outside of Richmond, say, had really been like that what would it have looked like? Warm, smiley, friendly no violence or anger or retribution. Freedom, wealth, and privilege burdens that black people were lucky to avoid. The only possibility of such a universe, I would imagine, might have involved some sort of depraved mass lobotomization or heavy doses of obliterating narcotics. This vision of the old South was as impossible as it was untrue.

If 1840 outside of Richmond, say, had really been like that what would it have looked like? Warm, smiley, friendly no violence or anger or retribution. Freedom, wealth, and privilege burdens that black people were lucky to avoid. The only possibility of such a universe, I would imagine, might have involved some sort of depraved mass lobotomization or heavy doses of obliterating narcotics. This vision of the old South was as impossible as it was untrue. Flash forward to mid-fifties New York, Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley in the new Andrew Scott Netflix version is approached by a black man at a bar who says he has a job for him. There is no reference to their races as if black people approaching white people and offering them work was a regular occurrence at that time. In the Highsmith original, no such character exists. Deeply racist, Highsmith cast almost all non-white characters in her work as foolish and/or despicable.

Flash forward to mid-fifties New York, Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley in the new Andrew Scott Netflix version is approached by a black man at a bar who says he has a job for him. There is no reference to their races as if black people approaching white people and offering them work was a regular occurrence at that time. In the Highsmith original, no such character exists. Deeply racist, Highsmith cast almost all non-white characters in her work as foolish and/or despicable.  Joseph H. Shieber, April 7, 2024 of Wallingford, PA. Beloved husband of Lesa Shieber; proud father of Samuel and Noa; loving son of Benjamin and Eileen Shieber; devoted brother of William (Rebecca) Shieber and Jonathan (Kathleen) Shieber.

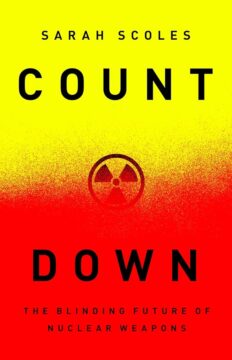

Joseph H. Shieber, April 7, 2024 of Wallingford, PA. Beloved husband of Lesa Shieber; proud father of Samuel and Noa; loving son of Benjamin and Eileen Shieber; devoted brother of William (Rebecca) Shieber and Jonathan (Kathleen) Shieber. As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it.

As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it.

A new study has revealed a troubling development in the state of Maryland: while murder rates fluctuated between 2005 and 2017—first trending downward, then increasing for a few years—the homicides recorded during that period have grown steadily more violent the entire time.

A new study has revealed a troubling development in the state of Maryland: while murder rates fluctuated between 2005 and 2017—first trending downward, then increasing for a few years—the homicides recorded during that period have grown steadily more violent the entire time.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory. All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

Is there such a thing as tasting expertise that, if mastered, would help us enjoy a dish or a meal? It isn’t obvious such expertise has been identified.

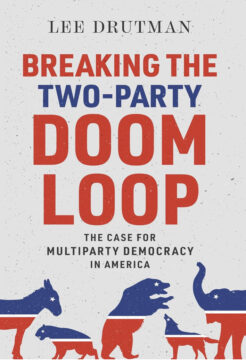

Is there such a thing as tasting expertise that, if mastered, would help us enjoy a dish or a meal? It isn’t obvious such expertise has been identified. It’s a book about how our political system fell into this downward spiral—a doom loop of toxic politics. It’s a story that requires thinking big—about the nature of political conflict, about broad changes in American society over many decades, and, most of all, about the failures of our political institutions. (2)

It’s a book about how our political system fell into this downward spiral—a doom loop of toxic politics. It’s a story that requires thinking big—about the nature of political conflict, about broad changes in American society over many decades, and, most of all, about the failures of our political institutions. (2) I’m writing this 37,000 feet above Vestmannaeyjar, a chain of islands off Iceland’s south coast. Or so the screen tells me – I can’t see the view because I’m wedged into 38E, a middle seat at the back near the loos.

I’m writing this 37,000 feet above Vestmannaeyjar, a chain of islands off Iceland’s south coast. Or so the screen tells me – I can’t see the view because I’m wedged into 38E, a middle seat at the back near the loos.

Kathleen Ryan. Bad Lemon (Creep), 2019.

Kathleen Ryan. Bad Lemon (Creep), 2019.