by Jerry Cayford

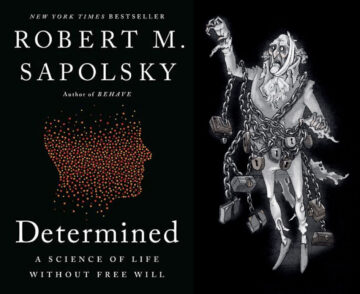

Robert Sapolsky claims there is no free will. Jacob Marley begs to differ. Let us consider their dispute. Sapolsky presents his case in Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will: everything has a cause, so all our actions are produced by the long causal chain of prior events—never freely willed—and no action warrants moral praise or blame. He supports this position with a great deal of science that was not available back when Marley was alive, though “alive” seems an awkward way to put it, since Marley is a fictional ghost, possibly even a dreamed fictional ghost (depending on your interpretation of A Christmas Carol), dreamed by fictional Ebenezer Scrooge. Marley’s standing to bring objections against Sapolsky seems pretty tenuous.

Nevertheless, Marley forthrightly rejects Sapolsky’s thesis: “‘I wear the chain I forged in life,’ replied the Ghost. ‘I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it.’” That there is a real dispute here is proven by Scrooge presenting a very Sapolskian argument against Marley’s right to bring a case at all: “You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato.” That is, only a chain of physico-chemical causes makes me, Scrooge, see you at all, let alone give any credence to your arguments about morality. If this rebuttal seems sophisticated for a fictional Victorian businessman, it at least reminds us that Sapolsky’s philosophical position is quite old and well known.

Unlike Scrooge, Sapolsky does not inhabit the same fictional realm as Marley’s ghost. He cannot argue that Marley’s sins were caused by prior conditions and events, because Marley’s sins and choices don’t really exist, not in the causal universe in which Sapolsky makes his argument. As he so emphatically puts it: “But—and this is the incredibly important point—put all the scientific results together, from all the relevant scientific disciplines, and there’s no room for free will.…Crucially, all these disciplines collectively negate free will because they are all interlinked, constituting the same ultimate body of knowledge” (8-9). Marley’s ghost, though, is not of that body—an “incredibly important point” indeed—and that’s precisely the reason to choose him as our spokes-“person.” Read more »

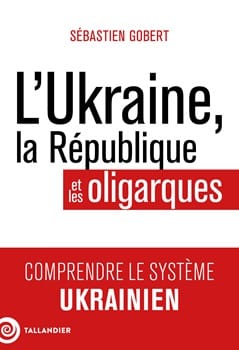

No matter where you go, Aristotle believes, the rich will be few and the poor many. Yet, to be an oligarch means more than to simply be part of the few, it means to govern as rich. Oligarchs claim political power precisely because of their wealth.

No matter where you go, Aristotle believes, the rich will be few and the poor many. Yet, to be an oligarch means more than to simply be part of the few, it means to govern as rich. Oligarchs claim political power precisely because of their wealth.

An abstract paradox discussed by Yale economist Martin Shubik has a logical skeleton that can, perhaps surprisingly, be shrouded in human flesh in various ways. First Shubik’s seductive theoretical game: We imagine an auctioneer with plans to auction off a dollar bill subject to a rule that bidders must adhere to. As would be the case in any standard auction, the dollar goes to the highest bidder, but in this case the second highest bidder must pay his or her last bid as well. That is, the auction is not a zero-sum game. Assuming the minimum bid is a nickel, the bidder who offers 5 cents can profit 95 cents if the no other bidder steps forward.

An abstract paradox discussed by Yale economist Martin Shubik has a logical skeleton that can, perhaps surprisingly, be shrouded in human flesh in various ways. First Shubik’s seductive theoretical game: We imagine an auctioneer with plans to auction off a dollar bill subject to a rule that bidders must adhere to. As would be the case in any standard auction, the dollar goes to the highest bidder, but in this case the second highest bidder must pay his or her last bid as well. That is, the auction is not a zero-sum game. Assuming the minimum bid is a nickel, the bidder who offers 5 cents can profit 95 cents if the no other bidder steps forward.

Vitamins and self-help are part of the same optimistic American psychology that makes some of us believe we can actually learn the guitar in a month and de-clutter homes that resemble 19th-century general stores. I’m not sure I’ve ever helped my poor old self with any of the books and recordings out there promising to turn me into a joyful multi-billionaire and miraculously develop the sex appeal to land a Margot Robbie. But I have read an embarrassing number of books in that category with embarrassingly little to show for it. And I’ve definitely wasted plenty of money on vitamins and supplements that promise the same thing: revolutionary improvement in health, outlook, and clarity of thought.

Vitamins and self-help are part of the same optimistic American psychology that makes some of us believe we can actually learn the guitar in a month and de-clutter homes that resemble 19th-century general stores. I’m not sure I’ve ever helped my poor old self with any of the books and recordings out there promising to turn me into a joyful multi-billionaire and miraculously develop the sex appeal to land a Margot Robbie. But I have read an embarrassing number of books in that category with embarrassingly little to show for it. And I’ve definitely wasted plenty of money on vitamins and supplements that promise the same thing: revolutionary improvement in health, outlook, and clarity of thought. Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-portrait on a Young Douglas Fir, May 3, 2024.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-portrait on a Young Douglas Fir, May 3, 2024.