Monday Poem

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Mike Bendzela

As you slide toward retirement age, it becomes clear that you have not accomplished what you had hoped by this point in life and that the meaning of it all is still as unfathomable as it was when you were thirty. You have resigned yourself to the fact that you do not know half the things you thought you knew, but you do know for certain that what you do not know advances by orders of magnitude every day and will continue to do so long after you are dead. The boundaries of human extravagance leap forward light-years by the minute without waiting for you and there is no point in trying to keep up. Might as well spend your remaining time on the planet thumping your fingernail against a string.

*

Hundreds, perhaps even thousands of years ago somewhere in Africa, a village wag became bored with banging an animal hide-covered hollow gourd with his mere hands. So, he attached a stick to the gourd (it could very well have been she; perhaps she wanted to stir men out of their torpor), ran two or three strings of plant fiber from the top of the stick to the base of the gourd, and thumped the strings against the animal hide top, a sound that immediately seized hearts. The villagers couldn’t help dancing. It’s inspiring to know our predecessors were as bored with monotony as we are today and made stuff up as they went along. Even this short history is half fable.

*

This innovation made its way to the New World via the slave trade. Like any entity in a Darwinian universe that gains a foothold in a new geographical location, the immediate response was adaptive radiation. The entity spread widely and became fixed in the population. Mutations ensued: Gourds and fibers were substituted with wood and steel; bridges, strings and frets were added or subtracted; styles multiplied and diverged, fruitfully. One struck the strings with one’s fingernail and thumb, or with finger picks, or with plectrums. These respective cults of the banjo retreated to separate corners of the continent, appearing at square dances, in minstrel shows, on steamboat decks, finally in jazz bands and even concert halls. They would all come to rub elbows again at latter-day banjo camps. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

In the shapeless but often suggestive scatter of stars across a dark night sky, humans have picked out patterns and woven countless tales around them, giving the brighter stars names for their place in these stories. The star names we use today can be fascinating but also baffling—which is not surprising, considering that they’ve evolved over centuries in various languages.

Most of the traditional star names known to Western science have Arabic, Greek, or Latin roots. Some of these names have fairly straightforward meanings, although the connections are not always obvious. Orange-red Antares, for example, is named for its resemblance to Mars (the name can be translated as rival of Mars). Regulus means little king; the star has long been associated with royalty, and it’s in the constellation Leo, the lion (king of the beasts). Spica is the brightest star in the constellation Virgo (the maiden); its name is derived from a Latin term for an ear of wheat, because of the constellation’s identification with a Greco-Roman goddess of agriculture. It has been identified with many other female deities over time.

There’s also a star in Virgo named Vindemiatrix, which translates from the Latin as grape gatherer, because in classical times, when it was named, the Sun was in Virgo during the grape harvest. A star in Lyra (the lyre) is named Sulaphat, which is derived from an Arabic word for tortoise. It puzzled me to learn this; the reason is that lyres were often made from tortoise shells. The name of Arcturus, in the constellation Boötes (the herdsman), is derived from a Greek term meaning guardian of the bear, for several possible reasons involving myths about bears. Read more »

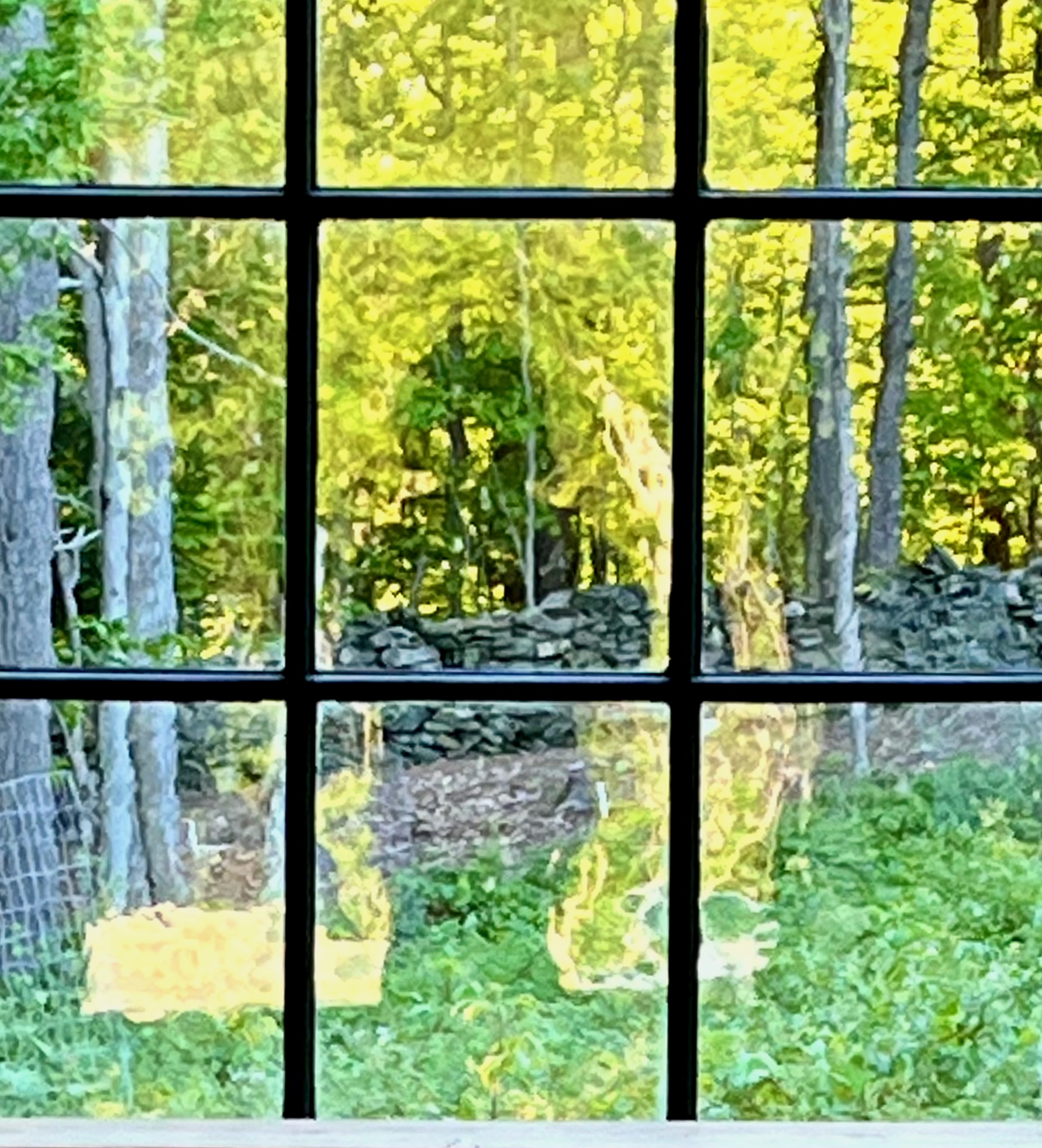

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Early Summer, May 2024.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Early Summer, May 2024.

Digital photograph.

by David J. Lobina

So, then, is the American politician Ron DeSantis a fascist? Is former (and maybe next) US President Donald Trump a fascist? What about the Republican Party these two politicians belong to, is it a fascist party? Are some strands within the modern British Conservative party, to move to this side of the world, a case of fascism too? And is fascism also present, to now move out of the English-speaking world, in the current governments of Italy, Hungary, and Russia or the various opposition parties in France and Spain?

These are some of the questions I have alluded to here and there since my post on the use and abuse of the term fascism in current political commentary, the first of a series of on Nationalism and Fascism. It might be a bit Procrustean to claim that all these currents (and undercurrents) encompass fascism, but this is exactly what one finds in the media, especially in the English-speaking world. In fact, there have been further cases of this sort of talk since my opening salvo, including from the very people I had singled out at the time, whilst the reaction the post received, both publicly and privately, was quite interesting in itself – trebles all around for doubling down!

So, to recap post number 1. The word “fascism” comes from the Italian fascismo, and the political phenomenon is also Italian in origin, properly starting in the 1920s. Both the word and the politics were soon adopted in other parts of Europe, and eventually elsewhere in the world, under different conditions and often becoming, naturally enough, slightly different phenomena. Thus, whilst it is customary, and correct, to consider Mussolini’s and Hitler’s regimes as fascist under a certain reading, Fascism and Nazism (in capital letters) were different in rather important respects, and plenty of scholars treat them as distinct ideological and political movements. Renzo De Felice, for instance, an early and quite influential expert in fascism, did not regard Nazism as a species of Fascism at all, and he argued this was even more the case for Franco’s regime in Spain or Salazar’s in Portugal.[i] Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

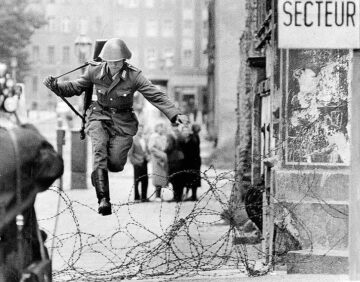

The Cold War ended somewhere between 1989 and 1991 or if you take the disintegration of Yugoslavia into account, maybe into the 2000s. It is now seen as the end of an era, a closed loop in history. It started with the Communist revolution in 1917 and ended with the end of one-party communist rule in Eastern Europe. The dissolution of the Soviet Union especially signaled the end of the debate about the two supposedly opposing economic systems. The argument goes that communism as practiced in the second world proved unable to keep up with the productive capacity and flexibility of the western capitalist systems, which (many believed) were underpinned by truly democratic norms.

But what if it’s not the struggle between capitalism and communism that was really at the heart of the twentieth century, but was really a more expansive struggle within the world system that developed since the sixteenth century? What if we’re still in the midst of it? I argue that there was a deeper conflict rooted in the debate over who gets to decide how our societies function. This struggle reaches back to the past and shapes our present. We can see this deeper struggle within the communist-capitalist conflict, as that narrative allowed the US and the Soviet Union to double-down on various bad-faith actions with regards to either their own populations or their actions abroad. The fight is between democracy and authoritarianism, the people and the powerful. Democracy clashed with the authoritarian reactionary forces since before the age of revolutions, making the Cold War merely a part of a larger dialectical discourse of the modern world. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Steve Szilagyi

After eight years writing publicity for a cable television network, I was let go. Just in time. I was hankering to get out of Manhattan, go back to my hometown, and marry a girl I knew in high school. Once I’d gotten all that out of the way, I found myself in need of a job. The rust belt city of my birth offered nothing as glamorous as the position I’d left. So I took a job at the local hospital – which happened to be a top-ranked academic medical center. They needed someone to write their employee newspaper. I thought I’d do that humble task for a few years, then retire and lead the literary life. You see, I’d written a novel, and I was pretty sure it was going to be a hit. And it was.

Somehow, the tumblers of fate fell into place and unlocked the doors to an agent, publisher, good reviews, and, finally, interest from Hollywood. In between writing for the hospital, I was doing interviews, book signings, TV, and radio. On my lunch hour, I stuffed coins into a hospital pay phone, calling Los Angeles and London, while producers bid for the right to film my book.

The movie starred an Academy Award-winning Best Actor, and I got a standing ovation at the North American premiere. The money was good, but it didn’t last forever. And I never missed a day at the hospital if I could help it. Week after week, I plugged away at the employee newspaper. My second novel didn’t come so easily, living as I was in a small house with a child.

That was okay. I was being drawn into the world of medicine. An essentially silly man, myself, I was in awe of these serious people. They didn’t know or didn’t care about the book or the movie. I worked hard to prove myself, and eventually became a kind of writer-at-large for the physician leadership. One year I was writing promo copy for Rodney Dangerfield; the next year, I was writing speeches for brain surgeons. Read more »

by Daniel Shotkin

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau prophetically declared that “we badly need someone to teach us the art of learning with difficulty.” Two hundred and fifty years later, Rousseau’s words seem clairvoyant in their relevancy to schooling in the United States. Education has come to the forefront of the array of issues emerging in the post-Covid era. The abandonment of the alphabet soup of standardized tests, student reliance on Chat GPT, and rampant grade inflation all point to a wider problem. And though some politicians see the Ten Commandments as the solution to classroom troubles, universal progress toward a real solution seems far away. Not that some don’t try.

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau prophetically declared that “we badly need someone to teach us the art of learning with difficulty.” Two hundred and fifty years later, Rousseau’s words seem clairvoyant in their relevancy to schooling in the United States. Education has come to the forefront of the array of issues emerging in the post-Covid era. The abandonment of the alphabet soup of standardized tests, student reliance on Chat GPT, and rampant grade inflation all point to a wider problem. And though some politicians see the Ten Commandments as the solution to classroom troubles, universal progress toward a real solution seems far away. Not that some don’t try.

Joe Feldman is not an activist; in fact, until recently, he was simply an attentive principal. Working for over twenty years in education, Feldman compiled stacks of hard data trying to answer one question: why was grading so inconsistent among his colleagues?

Two students enrolled in the same course put in a dramatically different amount of work yet shockingly got the same grade. In two classes of the same course, one got 70% A’s, while another received a much smaller 40%. Their grade essentially depended on the leniency (and frighteningly biases) of their teacher, and not on the contents of their course. This discovery correlates with the wider issue of grade inflation; from 2010 to 2022, the percentage of B and C students in all subjects declined, while the number of A students increased. Feldman relates this data to one idea—that student-teacher relationships have to be based on equity.

This idea is laid out in his latest book—Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms. Feldman believes that for many teachers, equity can be a concept that is far too easily brushed off because “teachers use grading practices that are traditional and end up perpetuating achievement and opportunity gaps.” Read more »

by Barry Goldman

Laws do not interpret themselves. No matter how carefully drafted, the language of a law can never be exhaustive and exclusive. Its boundaries will be imprecise, there will be vagueness and ambiguity, and there will always be a tension between the letter and the spirit. Statutory interpretation inevitably requires reasoned judgment.

Not everyone is happy with this state of affairs. For centuries there has been an effort to squeeze the judgment out of the legal process and reduce it to a rote exercise. In the 17th century John Selden wrote:

Equity is a roguish thing. For Law we have a measure, know what to trust to; Equity is according to the conscience of him that is Chancellor, and as that is larger or narrower, so is Equity. ‘T is all one as if they should make the standard for the measure we call a “foot” a Chancellor’s foot; what an uncertain measure would this be! One Chancellor has a long foot, another a short foot, a third an indifferent foot. ‘T is the same thing in the Chancellor’s conscience.

Selden has a point. We want the law to be clear, and we want it to be uniformly applied. We don’t want judges (or labor arbitrators) to make rulings simply according to their personal preferences. Legislation is the province of the legislature, not the judiciary. All that is true. But when interpretation is required, what should be the judge’s guide? Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

Humans, Plato famously held, are featherless bipeds: uniquely singled out from other animals by walking permanently on two legs, which delineates us against fish, mammals, and reptiles, while not sporting the sort of plumage associated with birds. Of course, he knew little of the mighty T. Rex (although its featherlessness is subject to recent academic dispute), and Diogenes the Cynic quickly came up with a deflationary argument: he crashed Plato’s school, brandishing a plucked chicken.

Plato was engaged in a project that goes on to this very day: the definition of what, exactly, is it that makes humans human—how we are distinguished from all else that creeps and crawls on the face of the Earth (and presumably, beyond). However, as performatively illustrated by Diogenes, such an endeavor is intrinsically fraught: defining the human is not just a matter of practicality, but what—or who—counts as human impinges on questions of moral standing, of whether to extend certain rights and protections. A standard human, if such a thing existed, would be a norm against which all are compared, and either permitted to enter ‘club human’ or not.

Even this is a simplification, however. The line, here, is not as clear as ‘human’ and ‘not human’—frequently, in the history of humanity, we encounter various categories of ‘human, but’: people that count as human, but not as the special sort of human, the ‘standard human’ that forms the measure of what it means to be truly worthy of all the rights and protections that society affords its most highly valued members.

This too is exemplified in the story of Plato’s featherless biped: what he was trying to define was man, not human. While we might count this as a quirk of a bygone time, or of the ancient Greek language, this attitude is pervasive throughout history, and finds its echo both in overt ostracism of ‘nonstandard humans’ and in subtle slanting of the playing field against those that don’t quite measure up. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has reminded everyone of how dangerous a world we live in. As rich countries scramble to rebuild militaries dismantled by post-Cold war complacency, one of the other problems of national success has become apparent: young people have better things to do than play soldier.

My solution: conscript the old instead

Armies have a recruitment problem: they can’t get enough healthy young men to join. Young men have traditionally been the best recruits for fighting wars. They can carry lots of equipment over long distances without getting too tired to fight afterwards. They generally lack a visceral awareness of their own mortality, so they can be ordered to do insanely dangerous things. Indeed, many of them rather enjoy the excitement, intense camaraderie, and sense of shared purpose that accompanies war-fighting, and the survivors look back on it fondly when they have grown old and boring. As only partially formed adults, young men conveniently also lack the self-confidence and resources to question orders and hierarchies.

Most crucially, until very recently young men have been cheap, plentiful and easily replaced. The death of an 18 year old man was no great loss to a pre-industrial society, since it didn’t represent any great stock of human capital. (It did represent a stock of muscle power, but subsistence economies were generally constrained by the available land rather than the labour supply to work it.) Fertility rates were high so lost men could easily be replaced as long as plenty of fertile women remained. Altogether then, the cost of using up vast numbers of young men’s lives in warfare was quite affordable and hence commonplace. (Archaeological estimates for male mortality rates by violence in the hunter-gatherer societies that my students like to romanticise range from a terrifying 5% to a scarcely imaginable 35%, and sometimes even higher – see e.g. the research summarised by Azar Gat.)

Young men are still the ideal recruits for war-fighting. But their lives are far more valuable than they used to be, thanks to demographic and economic changes over the last 200 years (the drivers and consequences of the rise of capitalism). Read more »

by Derek Neal

Have you ever read a book that you thought you were going to write? A book that captures something you’ve experienced and wanted to put into words, only to realize that someone else has already done it? The Apartment by Greg Baxter is that book for me.

Have you ever read a book that you thought you were going to write? A book that captures something you’ve experienced and wanted to put into words, only to realize that someone else has already done it? The Apartment by Greg Baxter is that book for me.

The Apartment was published in 2012 as Baxter’s debut novel and follows an unnamed American as he looks for an apartment over one day in a cold and snowy European city. Interspersed in his search are flashbacks to his home in America, his deployment in Iraq, and various encounters he’s had while living in Europe. He’s accompanied by Saskia, a local woman intent on helping him, as well as a few other characters they meet throughout the day. This is the extent of the plot.

I’ve thought about writing a story or a novel for years about an American in Europe. I wrote a short story based on an experience in Italy, submitted it to a competition, and promptly forgot about it. I’ve started multiple other stories based in Turin and Nice, France—both places I’ve lived—which are scattered throughout notebooks and Microsoft Word files. Sometimes these stories have plots; sometimes they don’t. What I’m more interested in is atmosphere and style. Baxter seems to have a similar approach. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Rebecca Baumgartner

The transformation of bringing a child into one’s family is conceptualized differently by different folks. It is rare, however, to encounter a parent who questions whether parenthood is any kind of transformation at all. This is the provocative stance taken by Anastasia Berg in her piece “What If Motherhood Isn’t Transformative at All?”

Berg is a philosophy professor at UC Irvine. She is also a mother who is very invested in not being changed by the experience of motherhood – or at least, in having us think that she is very invested in not being changed by the experience of motherhood.

The article purports to be about “the pitfalls of treating motherhood as a transformative identity,” but it’s not actually about those pitfalls at all. What it’s actually about is Berg’s reluctance to be a certain type of mother, and her insecurity about whether this necessarily makes her a bad mother. She doesn’t say this explicitly, mind you; this is a piece that presents the facade of vulnerability, while building an elaborate bastion against vulnerability with every sentence. Despite coming from an ostensibly feminist starting point, Berg puts forth a viewpoint that I find just as disingenuous, confining, and unsatisfying as the blanket dictum that parenthood should consume one’s life. Read more »

Voices Choir concert in Bozen, South Tyrol.

by Barbara Fischkin

I remember the day I realized that my cousin Bernard Moskowitz—my father’s nephew—was nothing like my other relatives.

The realization came in a flash as I spotted a newly arrived letter on the dining room table at our home at 4722 Avenue I in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. Two pages. Typewritten. It remains in my mind’s eye. I recognized the scratchy signature: It was my “Cousin Bernie.” I went back to the first page because that seemed like it was from somebody else It was embossed with these words:

Moorhead, Minnesota.

Professor B.B. Morris.

My mother, her eagle eyes in play, gazed through the opening from the kitchen and walked up behind me.

“Is this…,” I said

“Yes,” she replied, smiling. “Cousin Bernie got a good job. Daddy is so proud.” She paused. A worried look took over her face. “He changed his name. Maybe they don’t like Jews there.” Another pause. More worry. “It must be very cold.”

I imagined my mother sending Cousin Bernie a sweater. Or two. Or ten.

What else? A Star of David tie clip? A Hebrew prayer book? The possibilities were endless. Read more »