by Derek Neal

An essay about Stoicism appeared on this website about a month ago. The essay was critical, seeing Stoicism and its contemporary manifestation as a sort of individualistic therapy that excluded the possibility of political and collective action. Instead of attempting to improve society or grapple with its problems, the turn to Stoicism, the article seemed to be saying, allowed one to ignore political and social ills in favor of a personalized approach focusing on one’s wellbeing. This is probably true, at least with regard to the way Stoicism is portrayed on social media and the internet, but it is also an argument could that be made about almost any mental health approach, whether it’s ancient philosophy repackaged for the 21st century or a contemporary self-help routine.

An essay about Stoicism appeared on this website about a month ago. The essay was critical, seeing Stoicism and its contemporary manifestation as a sort of individualistic therapy that excluded the possibility of political and collective action. Instead of attempting to improve society or grapple with its problems, the turn to Stoicism, the article seemed to be saying, allowed one to ignore political and social ills in favor of a personalized approach focusing on one’s wellbeing. This is probably true, at least with regard to the way Stoicism is portrayed on social media and the internet, but it is also an argument could that be made about almost any mental health approach, whether it’s ancient philosophy repackaged for the 21st century or a contemporary self-help routine.

This may simply be a result of living at the end of history. When other possible constructions of society become unimaginable, there is no reason to diagnose society’s ills because one cannot hope to change them. Thus, one turns inward, or, on the other hand, embraces their fate by turning themselves into a self-optimizing marketable product. What other choices are there? My father and I were discussing this the other day when planning the movies we would watch at our family cottage. At the moment, our favorite genre is European thrillers about political corruption from the 70’s. So far, we’ve watched French Conspiracy (1972), Illustrious Corpses (1976), and next on our list is Z (1969) by Costa-Gavras. In these films, everyone is guilty; everyone is corrupt. The people who try to do the right thing end up sacrificing their ideals, or if not, dead. There is no escape. My father argued that this genre doesn’t exist anymore because it was one that expected the audience to be outraged by political scandal. Now, we are desensitized. Scandals come and go with such regularity that we turn off the news and go do yoga instead. I, being a millennial, argued that this was, on the whole, a sensible choice. My father was disconcerted by this but found it difficult to disagree.

The article on Stoicism drew gentle rebukes from a few commenters, mainly because some readers understood the author to be talking about ancient Stoicism, when he was really focused on the stoic self-help peddled on YouTube and TikTok. People were quick to point out that Stoicism can be political, and that we can’t criticize Stoicism simply based on the way it’s represented on social media. These are valid points, but I also understand the author’s point of view; perhaps it is simply difficult to fully distinguish these two strands of Stoicism since they are, after all, connected. In any case, I even made a comment myself. In mine, I outlined my own discovery of Stoicism, and the idea came to me about writing a sort of contemporary history that traced the increasing popularity of Stoicism. If you are not interested in Stoicism, or have not come across it on the internet, you may be surprised by my claim that Stoicism is popular. Stoicism, really? But if you share my demographic characteristics—millennial (or Gen X), post-secondary education, liberal arts major, male—there is a good chance you will have at least a passing familiarity with Stoicism.

I eventually forgot about the idea for my article, as frequently happens with article ideas, but then I came across another mention of Stoicism, this time in the issue of Harper’s that arrived in my mailbox yesterday. In it, a Professor of Philosophy and Classics at Yale had written a letter praising an essay on Stoicism in the previous issue. The professor, Brad Inwood, wrote, “I share Tom Bissell’s dismay at what many popular writers have done to Stoicism as they strive to make it accessible to modern readers.” Hey, I thought, I’ve gotta go read this—this was exactly the point of my comment! But then, another thought: my Stoicism essay—had someone beaten me to the punch? I pulled out my desk drawer and began to rummage through the back issues stuffed in there until I found the correct one—the Gwyneth Paltrow cruise ship cover (yes, really). I started to read the essay, and the writer, Tom Bissel, began to highlight examples of contemporary Stoicism: Stoic TikTok, a Stoicism subreddit with half a million followers, Ryan Holiday’s books and YouTube channel. Damn! I’d been scooped.

I’m being a little facetious, of course. Bissell’s essay is also part memoir, detailing the way Stoicism helped him deal with his father’s death, and I don’t believe any subject can ever be truly exhausted: each writer brings their own personality and style to the topic. What Bissell’s essay made me realize, along with my own encounters with Stoicism and the essay on this website, is that the topic of why Stoicism is popular and who it appeals to is just as interesting, if not more so, as the fact that Stoicism is popular at all.

Let me trace my own interest in Stoicism and how it came about, as I believe my story may be similar to those of others who have recently discovered Stoicism. In high school, back around 2010, I used to watch Tim Ferris’ videos. Tim Ferris is what might be called a “lifestyle guru.” He blogged and wrote books (now he has a podcast) about ways to “improve performance” and “increase efficiency” in the realms of diet, fitness, work, and relationships. He is one of those people—usually male, bald, 30-50 years old—who believes himself to be hyper rational and logical. These people, I find, are usually delusional. They think they can “hack” the human experience, but their hubris prevents them from ever achieving self-awareness. Nevertheless, Ferris introduced me to many interesting ideas, and I cannot exclude myself completely from the group I’ve put him in with, although I still have my hair. Writing this essay even led me to see what he’s up to now, and in one of his new videos of “The Random Show” (my favorite episodes from the past), I found him to be a likeable host, able to laugh at himself and no longer with the desire to come off as the smartest person in the room.

I believe Ferris mentioned the book A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy by William B. Irvine in one of his old videos, or if he did not mention it directly, his frequent talk of Stoicism, Marcus Aurelius, and Seneca led me to discover the book. In this book, Irvine, a Professor of Philosophy, gives a history of Stoicism while also showing how it can be used in contemporary life. Published by Oxford University Press, it is written for the general public, but unlike other popular books on Stoicism, it still retains an academic quality.

Irvine is quick to point out common misconceptions about Stoicism, including his own. He writes that Stoics did not seek to eliminate emotion from their lives; instead, they sought to eliminate negative emotion. Stoics, he says, could be happy and joyful. In addition, Irvine notes that ancient Stoics were not “passive individuals,” but “were fully engaged in life and worked hard to make the world a better place.” Finally, he mentions that Stoics viewed fame and fortune as not worth pursuing—putting him at odds with other proponents of Stoicism (and other ancient philosophies) who seek to extract its practical use for the express purpose of fame and fortune.

The main section of the book is dedicated to what Irvine calls Stoic techniques. These strategies are tools that can be used to help one live a better life. Some examples are: “negative visualization” (imagining loss in order to appreciate what you have) and the “dichotomy of control” (understanding what you can and cannot control). Irvine encourages his readers to practice the techniques he outlines in order to lead a good life and also addresses criticisms he expects readers will have (How can we know what’s in our control? How can we avoid complacency when practicing Stoicism?).

Since I first read this book over 10 years ago, I’ve had to do some research to reacquaint myself with its ideas. In doing this, I’ve also unearthed various versions of the debate that played out on this website last month. It seems that some academics found Irvine’s book unfaithful to ancient Stoicism, and in attempting to make Stoic teachings practical for the modern reader, they say he’s distorted its true meaning. It would seem then that each book on Stoicism exists somewhere along a spectrum: on one end we have the writings of actual Stoics, such as Seneca, and on the other hand we have people who only care about the practical parts of Stoicism that can help them achieve their goals. In the middle we have Irvine’s book. The question then becomes, not why is Stoicism popular, but why is something that has been branded as Stoicism become popular?

The first reason is that it works for many people. The techniques Irvine mentions, if one tries them, are useful in increasing one’s tranquility and decreasing anxiety. When I discovered Irvine’s brand of Stoicism in high school, I used it to help when I played sports. I had always been a good athlete, but at times I would begin to think too much, which is the worst mistake one can make in athletic competition. If you want to field a ground ball, you can’t think about fielding a ground ball, you just have to do it, trusting your muscle memory and practice. Applying Irvine’s techniques, I was able to, in effect, turn off my brain, and let my body do what it knew to do. I suspect many other recent converts to Stoicism value it for its ability to slow down and quiet one’s mind.

There are many strategies, however, that can achieve what I’ve highlighted above. What makes Stoicism stand out from its alternatives? I’ve repeatedly emphasized in this article that the people attracted to and promoting Stoicism often fit within a certain demographic. They are men. They are relatively young. They believe themselves to be logic and rational. They are frequently tech savvy. They may consider themselves to be “entrepreneurs.” They probably go to the gym. What Stoicism is for them, I think, is a form of therapy. Men don’t like to go to therapy. But what if, instead of going to therapy, you could become a Stoic? You could read snippets of ancient philosophy, follow the commands of a Roman Emperor, and not jeopardize your masculinity in any way?

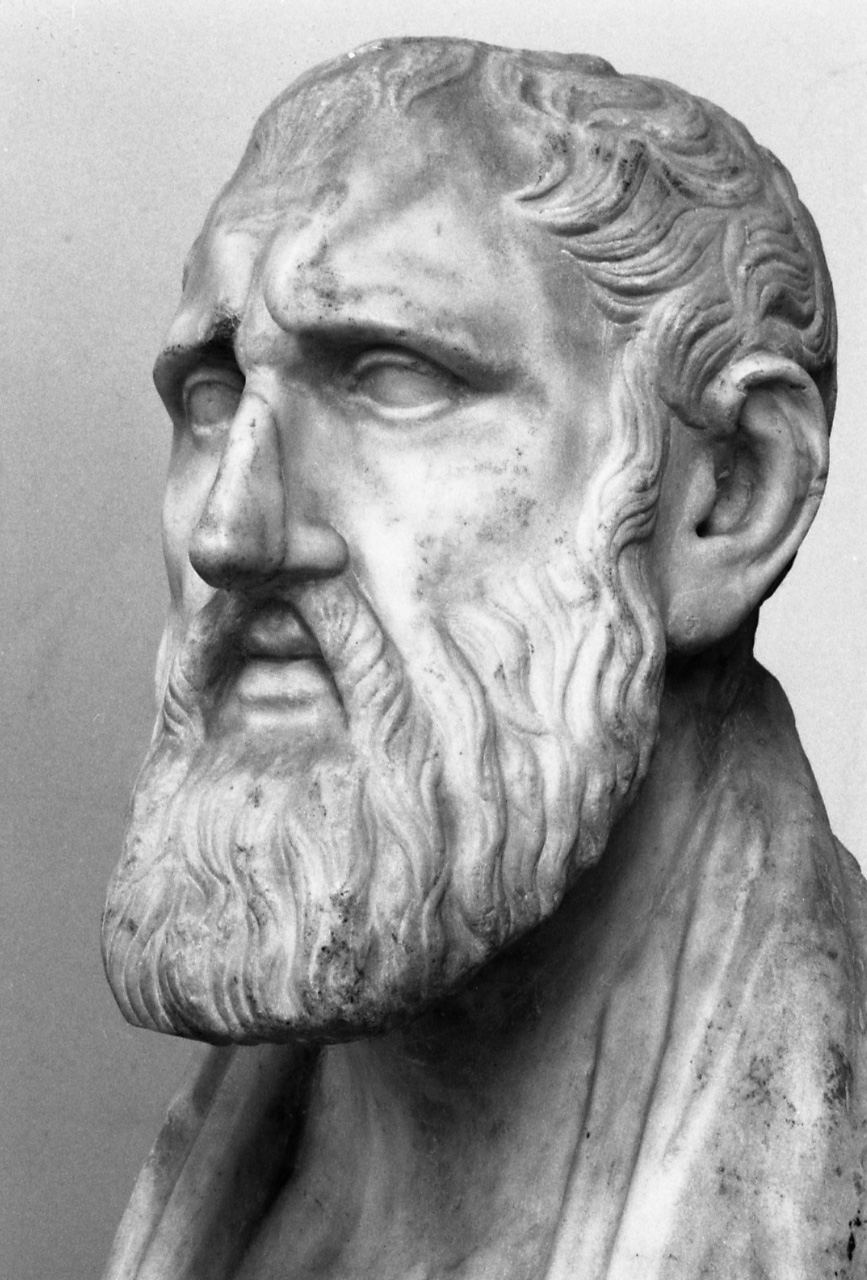

Bissell mentions in his Harper’s article how he focused on Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, a primary text of Stoicism, as well as contemporary accounts of Stoicism, but also came across “pop-inflected forms of neo-Stoicism.” This latter category is the one that I believe appeals to people on social media, while also being cast as representative of Stoicism by people who dismiss the philosophy in all of its current forms. Bissell notes how proponents of Stoicism on social media can “tilt into men’s right tantrums” and that in his search for Marcus Aurelius quotes on Twitter, “a good rule of thumb became clear: If an account had as its avatar Marcus’s renowned visage from the Musei Capitolini statue in Rome, and the account wasn’t that of an actual classicist or museum worker, I was almost certainly dealing with a user whose genteel gateway would soon lead me down a corridor of outright fascism.” Fascism might be a little hyperbolic, but I understand Bissell’s point. Somehow, Stoicism can end up “adjacent” to other things like anti-vaxxing or pick-up artists. Apparently, Andrew Tate is a proponent of Stoicism, and Jordan Peterson, while not claiming to be a Stoic, seems to be frequently connected to Stoicism by his followers. In a recent article called “The Revival of Stoicism” (this is the one that really scooped me, written all the way back in 2021!), the author, Shayla Love, mentions that some people refer to this strand of Stoicism as “Bro-icism,” and that a recent book by Mark Zuckerberg’s sister, of all people (she’s a classicist), documented the phenomenon of “far-right men who gravitate towards Stoicism to validate misogynistic and racist beliefs.”

“Stoicism,” it seems, can be anything to anyone, and it can lend a veneer of credibility to whatever it is connected to. In my own case, I feel grateful that I discovered Stoicism in the way that I did. After a couple years of being seriously interested in it, I moved away from it and didn’t think of it for a long time. But it just won’t go away, and despite its more insidious manifestations, there are accounts of Stoicism that I believe to be worthwhile. Besides the two articles I’ve mentioned, I was reminded of Stoicism about 18 months ago when I decided to create a lesson focusing on Ancient Greek Philosophy, specifically Cynicism, Epicureanism, and Stoicism. As research for the lesson, I went back to Irvine’s book, and I discovered that Irvine had become interested in Stoicism based on its representation in Tom Wolfe’s A Man in Full (1998). In the novel, a character named Conrad Hensley is mistakenly sent a volume of Epictetus’ writings while in prison. He becomes enthralled with the Stoic ideas he’s reading, and upon escaping prison, he crosses paths with another character in the novel, a larger-than-life real estate developer who’s fallen on hard times. The developer, named Charlie Croker, takes a liking to Conrad’s Stoic ideas. At the end of the novel, Conrad returns to his family to live a quiet, tranquil life, while Croker becomes an evangelist, spreading Stoicism in the South until he secures a deal with Fox to host a show called The Stoic’s Hour. In these two representations of Stoicism, perhaps we have a representation of the way the philosophy has spread in the 25 years since the publication of Wolfe’s book.

Wolfe, I believe, has to be credited with the revival of Stoicism. While I’m unable to draw a straight line from him to the present, some internet digging has turned up a few interesting facts. A New York Times article from January 2, 1999, mentions how Wolfe’s book was helping revive interest in Stoicism. An article from the Baltimore Sun on May 3, 1999, tells of how a book on Epictetus’ teachings, The Art of Living: The Classic Manual on Virtue, Happiness and Effectiveness by Sharon Lebell sold more copies in the three months after Wolfe’s book was released than in the two years prior. Ryan Holiday, who is the face of Stoicism on social media and, I think, the person who introduced Tim Ferris to Stoicism, has a blog post from March 30, 2007, where he lists the books he’s been reading, which include Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, the Discourses of Epictetus, and Wolfe’s novel, A Man in Full. Elsewhere, Holiday has written he was recommended Meditations by Dr. Drew Pinsky (yes, the one from TV) around this time, which then led him to Stoicism. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to discover if Pinsky discovered Stoicism by reading A Man in Full, but Wolfe’s influence is clear, as is his prediction of the various turns Stoicism might take in the 21st century.