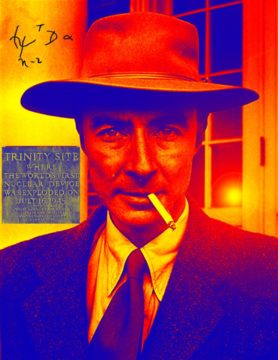

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

This is the eighth in a series of essays on the life and times of J. Robert Oppenheimer. All the others can be found here.

After his shameful security hearing, many of Oppenheimer’s colleagues thought he was a broken man, “like a wounded animal” as one colleague said. But Freeman Dyson, a young physicist who was as perceptive of human nature as anyone, saw it differently: “As far as we were concerned, he was a better director after the hearing than he was before.”

Director of what? Of the “one, true, platonic heaven”, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, a place where the world’s leading thinkers could think and toil in unfettered surroundings. It was here that Oppenheimer entered the fourth and final act of his life, one that was to thrust him on the national and international stages. There is no doubt that the hearing deeply affected him, but instead of dooming him to a life of obscurity and seclusion, it invested him with a new persona, a new role as a public intellectual in which he performed magnificently. Far from being the end of his life, the hearing signaled a new beginning.

It had been an unpromising start. “Princeton is a madhouse”, Oppenheimer had written to his brother Frank in a 1935 letter, “its solipsistic luminaries shining in separate and helpless desolation.” The institute had been set up by funds from a wealthy brother and sister, Louis and Caroline Bamberger who, just before the depression hit, had fortuitously sold their department store to R. H. Macy’s for $11 million. The philanthropic Bambergers wanted to give back to the community and sought the advice of a leading educator, Abraham Flexner, as to how they should put the money to good use. Flexner dissuaded them from starting a medical school in Newark. Instead he had a novel idea. As an educator he knew the importance of pure, curiosity-driven research that may or may not yield practical dividends. Later in 1939 he wrote an influential article for Harper’s Magazine titled “The Usefulness of Useless Research” in which he laid out his vision. Read more »

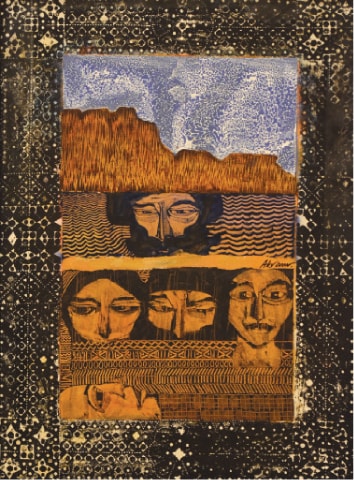

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”.

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”. The Lede

The Lede 1.

1.

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.”

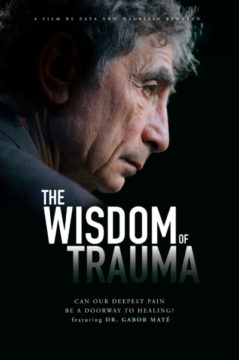

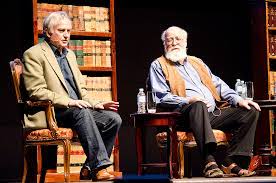

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.” He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual.

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual. Akram Dost Baloch. From the exhibition “Identities”, 2020.

Akram Dost Baloch. From the exhibition “Identities”, 2020.