by Chris Horner

Equality v Equity

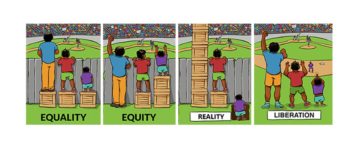

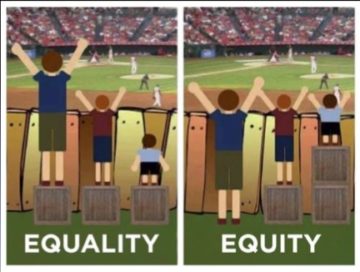

How should society go about the business of redistributing resources? Many people will be acquainted with the image featured at the top of this article. It is supposed to show the superiority of the notion of ‘equity’ – that is, giving people what they need to succeed, thus satisfying the demand for fairness that the equality approach is depicted as failing. Since people don’t start in the same place, due to gender, race, disability and so on, so the argument goes, an equal distribution is unfair: everyone goes up a bit, as in the image on the left, but since the differences haven’t been addressed, the result is unfair. So we need equity rather than equality. This is an example of an argument that looks persuasive at first glance, but which is deeply problematic when we consider it further. To see why, we need to go beyond the thought experiment approach to this issue, to see the social and political context in which it has become popular.

A first point to make is that no thoughtful advocate of greater equality has been blind to the importance of considering the needs of recipients. If equality is about justice, then it can’t just be mathematical equality. Giving the same amount of food to a malnourished person and a replete one would obviously be unfair. So if the current equity over equality argument is just saying this we could just see it just a difference in the terms one uses. But there is more going on with it than that.

DEI

The rising popularity of equity talk is associated with multicultural liberalism. There is the demand that there be a a more diverse representation of races, genders, etc in jobs, home owning etc. This is sometimes summarised as ‘diversity, equity and inclusion’ (DEI). There is an entire bureaucracy, a multi billion dollar business, devoted to training under this slogan. And greater diversity indeed looks fairer than the ‘pale, male and stale’ image of so many of our institutions in the public and private sectors. However, this push for DEI actually represents a political ideology that wants to avoid greater social equality in a very unequal society, and instead proposes that means testing should replace universal provision. It is the wrong approach to social justice, and is doomed to failure on its own terms.

Progressive Neoliberalism

DEI grows out of what Nancy Fraser calls ‘Progressive Neoliberalism’: the political project, associated with the centrist parties and their leaders (originally, Clinton, Blair, etc). This appropriated the campaigns and slogans of the new social movements of the 60s and 70s – for gay rights, feminism, civil rights, etc, while at the same time allowing the market greater and greater sway over the lives of citizens. An entire vocabulary goes with it, at the top of which are ‘empowerment’ and ‘choice’. So while got welcome legislation to outlaw hate speech, homophobia and so on, it largely replaced action by the state to promote or even defend social equality, much less transform it. The same discourse spread to corporations like Google and Facebook – committed to DEI while harvesting and selling data on their customers to the highest bidder. Capitalism was to be allowed to determine the fate of millions, now encouraged to see themselves as ‘entrepreneurs of the self’. Wages stayed frozen or fell, job insecurity grew, inequality skyrocketed. And ‘diversity, equity, inclusion’ began to have its day.

The Problem with DEI

The promotion of DEI tends to fragment people and groups into their particularities – into their identities as black, or gay, or female etc. The notion is that each group will get something appropriate to them that will help them on the road to success. This is both conceptually and practically mistaken. Conceptually, what it misses is the demand for universality. The left needs to stand with and for demands for the universal, not merely the particular and the identitarian. The demand for the universal arises when we see the injustice that denies the equal worth of all people. So the slogan ‘Black Lives Matter’, for instance, should be understood as pointing to the failure to treat all people as of equal worth. It isn’t really a demand for particularity, or for the advancement of an identity. And the complacent retort that ‘all lives matter’ misses because it cannot see that under the current system universality is denied: some people aren’t being treated as of equal worth and so their lives matter less.

Promoting Equity is a way of avoid any significant change to the system we have because it promotes particulars, identities, over universals. The best that might be achieved is that black, female, gay etc people will all get a fair chance of being exploited with a nicely representative group of people in the boardroom reaping the rewards. While there’s nothing wrong with a behemoth corporation having a diversity programme that puts more eg women in the boardroom, the real problem is the corporation itself, and an economy structured to let it suck value from all its workers, irrespective of their ‘identity’.

A Failed Project and a Better Alternative

And there is another reason to avoid the equity over equality approach: it is likely to fail. By promoting the particular under the watchword of equity, opposition grows, fuelled by resentment that special treatment is being meted out to certain favoured groups. This is gold for the reactionaries and conservatives who want nothing more than to pose in bad faith as the defenders of the rights of ‘ordinary’ working class people against ‘minorities’. The result is a damaging culture war that the right is likely to win. Identity politics is a right wing project, not a left wing one. It provides the ground on which conservatives and nationalists plant their flag.

Universal provision, funded by progressive taxation, can avoid this. Such provision, like the NHS in the UK, is perfectly able to vary its service according to different needs, due to inequalities and differences, which include those of race, gender etc. The same is true of any intelligently applied universal provision. Mere mathematical equality is not the automatic result of a universal programme. Universal provision, aimed at overcoming inequality, has the political advantage of creating ‘buy in’ on the part of the bulk of the population, as all can be seen to be benefitting and all are included. This makes it difficult for the bad faith culture warriors of the right to exploit differences between different groups.

That ought to be good reason to support universality over particularity, and equality over equity. I’d go further than that, though. The underlying problem is class. And class isn’t just another name for a particular group. It is the underlying structural feature of capitalism. As long as we have a class system we will not have a society in which all can flourish. Beyond equity and equality alike is the need for freedom from domination, from the constraints and alienation of capitalism. Instead of all this fiddle with boxes and fences we need to kick the damned fence down. But that is another story.