by Tim Sommers

How do we know that the external world exists in anything like the form we think it has? Assuming that we think, therefore we are, and that it’s hard to doubt the existence of our own immediate sensations and sense perceptions, can we prove that our senses give us reasonably reliable access to what the world is really like?

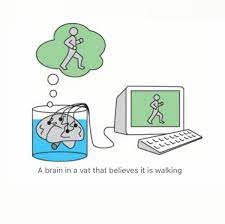

One thing that stands in our way is a variety of “skeptical scenarios” or “undefeated defeaters” (Knowledge is basically justified true belief without any undefeated defeaters.) Here are some well-known skeptical scenarios/defeaters: How do you know that you are not… (i) dreaming, (ii) being fooled by an evil demon; (iii) currently using a really good VR-rig; (iv) on a “holodeck” like the one in “Star Trek”, (v) currently in William Gibson’s immersive, plugged-in version of “cyberspace”, (vi) in “The Matrix” or, anyway, a matrix; (vii) in Nozick’s “experience machine”; (viii) a brain in a vat being electro-chemically stimulated to believe you are not just a brain and the world around you is going on as before; or (ix) part of a computer simulation? (You don’t need to recognize all of these to get the general idea, of course.)

David (“The Hard Problem (of Consciousness)”) Chalmers, in his new book “Reality+”, doesn’t want us to think of these as skeptical scenarios at all. Being a brain in a vat, he says, can be just as good as being a brain in a head. Most of what you believe that you know about, say, where you work, what time the bus comes, or how much is in your checking account is still true, relative to your envattedness, according to Chalmers.

It seems tenuous to me to claim that “most” of your beliefs could be true in such a scenario.

I don’t know how you individuate and count up beliefs, for one thing. (Donald Davidson, on the other hand, argued that it is always the case that, if you have any beliefs at all, by definition, most of them will be true.) But can’t we agree that if you are unknowingly a brain in a vat, there are some pretty significant things that you don’t understand about your situation, no matter how accurately you continue to be electro-stimulated to believe the the rest of the world hasn’t changed (and you still have money in your bank account). For example, you may be in danger of having your vat knocked over and dying as a result, whereas I don’t think that can happen to me.

But this isn’t the argument I want to have. I don’t want to examine these scenarios one at a time. I think the only scenario we need to look at to understand Chalmers’ central argument is the simulation one. In all of the other scenarios, notice, you still have all, or part, of your body left and involved. You are being gaslighted about the world around you and yourself, but you, and your body (which may be the same thing, in any case) are still in that world.

If you are entirely replaced by computer code, if you become part of a program, an abstract computational process, if you are part of a simulation, that’s very different than putting on a VR-rig or even being a brain in a vat. For one thing, if you exist only inside a program, I’m not sure what your metaphysical status outside of the program is – especially, whenever the program is not actively being run.

Technophiles tend to get ahead of themselves on this, I think. It’s not at all clear that anything even remotely like this is even possible. How do we even estimate how likely is it that one day you could be uploaded or programmed into a simulation or that there could be sentient programs or true artificial intelligence inside a computer simulation? (Is “inside” even the right word? “Part of”?)

The heart of Chalmers’ argument is that if there is any abstract computational process to simulate our actual physical space-time including us and everyone else, then that abstract computational process could turn out to be the real process that actually does underlie our world. Given that it could underlie the actual world, if the way that our world is actually implemented is irrelevant, then it doesn’t matter whether we live in a simulation, as simulations are just as real as non-simulations.

That’s a bit tricky. It’s a kind of a generalization of the idea of multiple-realizability: You can, maybe, feel the same pain as your neighbor or your dog or an alien or some super advanced android without having exactly the same underlying physical stuff going on. So, pain can be “realized” in different ways and the physical substrate in which it is realized doesn’t matter. Pain is pain, human or animal or silicon.

Chalmers is saying that the world itself is multiply-realizable. If there is any way that we could simulate the world completely computationally, then even if that simulation is not in fact how the world actually is, it’s just as real in the sense that it could be the way the world is and it wouldn’t make any difference – it would be just as real.

There’s less to that argument than there first appears to be. It’s circular, for one thing. If we could simulate you and world perfectly, then that simulated world would be just as real as the (as far as we know) unsimulated world in which we actually live. Right. If we could, we could. Why think we could?

In other words, without good reason to believe that we could make a perfect computational simulation of ourselves and the world and everyone else on top of that, this argument can’t get going. But, of course, if such a simulation were possible and could be perfect, then (by definition) it would be just as good as what it simulated.

I guess that part of the argument is fine as far as it goes – but it doesn’t go far. Here I just want to emphasize that this simulation stuff doesn’t reflect back on the other skeptical scenarios in the way Chalmers implies it does. Being in one computer simulation may be more or less as good, or as real as, being in another. But I think it’s clear that whether your brain is in your head or in a vat matters. Whether you are shooting people or just in a VR-rig pretending to, whether you are on the holodeck or facing Moriarty for real, if you don’t know which, then you don’t know what’s real and what isn’t. And that’s the point.

How do we unpack the claim that one situation is as “good”, or “real”, as another? “Real” avoids the question. The question is, ‘What’s true?’ Are you dreaming, a brain in a vat, in an experience machine or a computer simulation? That’s the question. If you can’t tell whether you are or not, then you can’t answer that question, and that’s a defeater to knowledge and a defeater for Chalmers’ claim that the virtual is just as good as the real.