by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Like other parents, we were delighted when our daughter started walking a few months ago. But just like other parents, it’s not possible to remember when she went from scooting to crawling to speed-walking for a few steps before becoming unsteady again to steady walking. It’s not possible because no such sudden moment exists in time. Like most other developmental milestones, walking lies on a continuum, and although the rate at which walking in a baby develops is uneven, it still happens along a continuous trajectory, going from being just one component of a locomotion toolkit to being the dominant one.

As paleoanthropologist and anatomist Jeremy DeSilva describes in his book “First Steps“, this gradual transition mirrors our species’s evolution toward becoming the upright ape. Just like most other human faculties, it was on a continuum. DeSilva’s book is a meditation on the how, the when and the why of that signature human quality of bipedalism, which along with cooking, big brains, hairlessness and language has to be considered one of the great evolutionary innovations in our long history. Describing the myriad ins and outs of various hominid fossils and their bony structures, DeSilva tells us how occasional walking in trees was an adaptation that developed as early as 15 million years ago, long before humans and chimps split off about 6 million years ago. In fact one striking theory that DeSilva describes blunts the familiar, popular picture of the transition from knuckle-walking ape to confident upright human (sometimes followed by hunched form over computer) that lines the walls of classrooms and museums; according to this theory, rather than knuckle-walking transitioning to bipedalism, knuckle-walking in fact came after a primitive form of bipedalism on trees developed millions of years earlier.

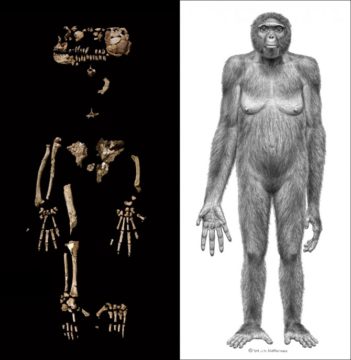

Bipedalism as we modern humans know it it first seems to have developed in the hominid lineage Ardipithecus about 4 to 5 million years ago, but this form of bipedalism was clumsy, slow and outright dangerous for walking around the grasslands that were then forming even as the forests were receding. “Ardi” whose toes were still curved and grasping rather than flat and mobile thus spent most of her time “walking” in trees, only descending and foraging for nuts or fallen fruit occasionally, ambling along in jerky spurts, keeping a watchful eye out for the apex predators that ruled over the landscape. As our human ancestry then progressed by manifesting itself in familiar names that have dotted the annals of both academic and popular paleoanthropological literature – Australopithecus afarensis, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis and finally Homo sapiens – every new discovery of new hominid forms newly challenged our view of when and how exactly humans started walking.

Paleontology and anthropology are both sciences powered to an unusual degree by blood, sweat and tears. A particularly enjoyable part of DeSilva’s book is the way in which it sheds light on the grueling workmanship needed to make bold extrapolations in these sciences, often predicated on crawling on all fours on hot afternoons in the sun-baked landscapes of Namibia, Ethiopia and South Africa as well as occasionally in the stone-cold caves and frost-ridden landscapes of Germany and Scandinavia. The discovery of any hominid fossil is messy, uncertain and subject to the ravages of space and time that introduces complications in dating the fossils using the age of the rock layers around them and even distinguishing them from the myriad surrounding fossils of non-hominid animals; in many ways it’s the very definition of trying to find a needle in a haystack of similar-looking needles. DeSilva’s excitement as he makes his way around fossil sites and bone vaults is palpable. Another book, Kermit Pattison’s marvelous “Fossil Men”, details the actual physical danger inherent in some of these expeditions even as their instigators make their way around politically unstable countries; preserving the invaluable artifacts in museums in some of these countries should be an international priority. A crucial debt American and European researchers – who have put together most of the grants and explorations describing new hominid discoveries in the last few decades – owe is to local African men, women and children whose astute eye for finding small, easily hidden bone fragments, tracks and footprints makes the discoveries possible. Some of these native Africans are now gratifyingly in charge of safeguarding their country’s paleontological heritage.

But whoever is involved in finding the subtle clues involved in unraveling the twisted thread of human evolution, there is no doubt that it is a science fraught with ambiguity and complexity. Researchers are often forced to make bold, potentially pathbreaking extrapolations not just about human anatomy but about human behavior based only on the odd fragment of a skull or ankle bone. At the same time, the very fact that we can extrapolate this way based on our knowledge of anatomy is fascinating: for instance, finding a single big toe bone that’s curved instead of flat immediately tells us that Ardipithecus wasn’t yet fully adapted to walking on the ground. Similarly, the bicondylar angle between the femur and the pelvic bones is hugely informative – among other things it told us why apes walk bow-legged and why narrowing the gap between knees was crucial for humans to walk upright, which combined with rapidly growing brains had very significant consequences for childbirth since it narrowed the birth canal in women and needed babies to rotate through the canal in ways that were inconvenient and even fatal.

As an aside, DeSilva also debunks some myths about walking in women versus men, for instance the myth that women walk in a more energy-inefficient manner because of their wider hips. In fact, as any new father who has tried to hold a baby on his hips and walk can tell you – I tried doing this myself – doing this is hard for men, and walking holding a child in your arms is rapidly exhausting. It turns out that because wider hips in women enable them to park their babies at a stable location, women actually expend about 20 percent less energy while walking with children, a fact of no small consequence in the prehistoric age when hominids could easily walk six or eight miles every day. Far from making them inefficient, women’s wider hips made locomotion for entire families possible. This locomotion sometimes left poignant, eerie footprints in the volcanic mud. There are few trains of thought more profoundly haunting than imagining what these tracks left by some of our direct ancestors indicated – who lived, who died, who sang songs, who played pranks, what the children were doing. Perhaps more consequentially, the fossil records indicate that many lineages of Homo walked separately in many parts of the world, both in Africa and beyond, sometimes being startled by other lineages that preceded them, consequently greeting, fighting and mating with them, as happened with Neanderthals and modern man. How and why Homo sapiens won out against its dozens of competitors and became the sole survivor of the Homo lineage is still an open question, in equal parts troubling and fascinating.

Figuring out the “when” of bipedalism based on isolated bone fragments and tracks is hard enough, but divining the “why” takes speculation to a whole new level – Richard Feynman’s “imagination in a straitjacket” writ large. Just like other evolutionary innovations, walking clearly had multiple potential advantages along with certain manifest disadvantages. The most important disadvantage was a reduction in speed relative to the speed of large predators roaming around in the African savannah. Even the fastest person on the planet today, Olympic sprinter Usain Bolt, runs at a top speed of a measly 27 miles per hour or so compared to the 35 miles per hour speed of even an ungainly bear, let alone the 40 miles per hour or higher speed of a lithe cheetah. Clearly, walking must have conferred some very significant advantages that overcame these deadly disadvantages. A very tempting hypothesis put forth by anthropologist Raymond Dart was that it enabled us to wield weapons by freeing up our hands. But the fossil record does not support Dart’s hypothesis; for most of our evolutionary history, especially before we developed large brains to conquer prey and when bipedalism was already entrenched, we were the hunted rather than the hunter.

Other hypotheses for bipedalism proliferate, many of them just-so evolutionary stories ringing out louder in the halls of Twitter than in staid academic journals. Some of the more amusing ones that DeSilva lists: The “Red Light District” – walking developed so that males could walk up to females and trade food for sex. The “Stealthy Stalker” – walking developed so that humans could sneak up on predators and hit them with rocks. “The Scrambler” – walking evolved to help humans scramble up hills and trees. Most of these theories will likely be consigned to the graveyard of evolutionary theories, but they also illustrate the difficulty in separating the wheat of what actually happened from the chaff of what seems almost reasonable but is impossible to definitively disprove. Nobody yet knows what dominant evolutionary adaptation bipedalism enabled, but knowing the complexity of evolutionary history and the feedback cycles among different evolutionary innovations that likely existed, it was almost certainly a confluence of factors. DeSilva’s favorite hypothesis, and one favored by some other scientists, is that bipedalism took pressure off our vocal apparatus – when animals walk or run on all fours, their internal organs crowd together and bump up against their neck and throat, needing them to pant – and allowed our voice box to develop. This, combined with the concomitant growth in brains fueled by cooking and omnivory, enabled us to kickstart the seminal revolution in our development of language and communication. The social interactions that language then engendered could have been a primal force for adaptively selecting bipedalism. This hypothesis is probably as attractive and unproven as some of the other ones, but it is more interesting and even possible, simply for the sheer consequences and selection pressure of the ensuing linguistic adaptation. The acquisition of language is of course perhaps the single-most consequential development in human evolution, and while this is not the place to discuss that fruitful consequence, it’s worth pointing out my favorite hypothesis for the origin of language, Danny Hillis’s “Songs of Eden” hypothesis which says that language developed from selection pressures on pleasing sounds emitted by ’singing apes’.

Bipedalism clearly falls into two distinct categories – walking and running. These are physiologically distinct enough motions, involving heel-first strikes for the former and toe-first strikes for the latter. The advantage of long-distance running in wearing down fast-moving prey in the savannah through sweating is not just considered conventional wisdom but is a strategy in contemporary hunter-gatherer societies. The !Kung bushmen of the Kalahari run down antelopes through day-long chases so well that they can gingerly approach the weakened animal and strangle it to death. In case this sounds cruel, it’s worth keeping in mind that this strategy likely made the difference between life and death for our African predecessors. As running down large prey started to become more prevalent, the value of social interaction networks that allowed us to kill, capture, skin, cook and eat as a social activity became paramount. In that sense, one of the undeniable secondary effects of bipedalism was our ability to survive in groups, communities and tribes, which through language led to the complicated structures of kin cohesion, mate selection and conflict with strangers that massively shaped human societies.

The last part of the book deals with modern incarnations of walking. Study after study seems to detail, seemingly in homage to this most primitive activity, the benefits of walking not just for warding off the modern maladies of cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes that were largely unknown to prehistoric man but even in strengthening neural connections and especially hippocampal volume, the latter directly responsible for improved memory in aging individuals. As little as 30 minutes of walking every day has been shown to have a pronounced impact on health. Not just that but walking can spur creative activity; DeSilva describes a range of thinkers, from Darwin to Thoreau who had some of their best thoughts while walking. Niels Bohr’s favorite habit was to have a sparring partner who could stimulate his thinking on long walks and hikes. Especially during the pandemic when people have been cooped up in their homes, the importance of walking for physical and mental health cannot be underemphasized.

Every human being has an intensely personal relationship with their walk. After the first atomic bomb test in the desert of New Mexico, the physicist Isidor Rabi described a chill going down his spine as he saw his friend Robert Oppenheimer who had successfully led the Manhattan Project walking erect and confident, “like High Noon”. Individuals are so distinctly mapped to their unique gait that this mapping is becoming not just a tool for early diagnosis of dementia and other related disorders but – more questionably – has started to be considered by law enforcement agencies as a complementary tool to facial recognition for identifying miscreants. But the personal manifestations of walking are much more mundane. Many years ago when I was laid off from my job, I felt inspired to start both walking and running by reading Haruki Murakami’s “What I think about when I think about running.” It nourished and challenged me and often sparked new thoughts, culminating in two half-marathons.

These days I walk an hour every day to clear my head and break the monotony of sitting at my desk. I do stop to smell the flowers and examine the insects, and I often use walks to dictate memos to myself and sometimes argue aloud while I work out some of the intellectual challenges I might be facing in my thinking. Passersby probably think I am a bit crazy, but this is the San Francisco Bay Area after all, and a man who talks when he walks is fairly low on the totem pole of the crazy index. When I feel self-conscious, I only think of the English physicist Paul Dirac who, when he moved from Cambridge, UK to Tallahassee, FL, raised eyebrows with his day-long recreational walks on Sundays. But perhaps what I should really do is think of the 4.4 million-year-old tradition and unbroken thread which I am a part of, walking in the steps of those families and tribes who left footprints in the African mud as they walked to escape predators, tend to their old, hold and talk to their babies, sing songs and find fresh sources of food, at all times being human. And that is what I am when I am taking a walk, human. That mundane realization is what sends a chill down my spine and puts a spring in my step.