From David Winner’s first column about his poignant relationship with buildings and their ornamentation, to Angela Starita’s discussion of the Bengali/Italian/Uzbek gardens of Kensington, Brooklyn as well her own growing up with her Italian-born father who became a farmer in middle-age, our column centers around place and what it signifies: architecturally, historically, emotionally. We will try to interrogate buildings: factories, apartments, houses, cities. Sometimes we will enter inside their doors to focus on what goes on inside.

by David Winner

When Angela and I visited Paris for the first time in the early nineties, we stayed in a large house near the Parc Monceau owned by a friend of my great-aunt’s, Henri Louis de la Grange, Mahler scholar and bona fide baron. When Alain, a former lover of Henri Louis, had us to dinner one night, he complained about a recent visit to Cincinnati. Echoing Gertrude Stein’s famous “no there there,” comment, he dismissed the city as “provincial.” When I repeated the comment to Henri Louis later over dinner with my great-aunt, he disdained Alain, from Normandy, as provincial himself.

That memory begs two questions. What constitutes provincial, and where and what is “there?”

Many students at the community college where I teach come from former colonies of the Spanish empire. Provincial backwaters to some: think poor Zama in Antonio de Benedetto’s eponymous novel, stuck in murky Asuncion, desperate to get transferred to Buenos Aires. My students often refer to the capital city of their country not by its name – Santo Domingo, Quito, San Salvador – but simply as “the capital.” After moving to Jersey City within spitting distance of Manhattan, those cities remain capitals for them, the antitheses of provincial.

*

I visited Riga, the capital of Latvia, which spent much of its recent history as a backwater of the Russian then Soviet empires, in the summer of 1997 when Angela was doing a program for journalists in Finland. I took the ferry across the Baltic Sea to Estonia, then a bus to Riga. The Soviet Union had only recently fallen, and it felt like a distant, exotic destination. Except it wasn’t. The well-preserved Old Town with its late seventeenth century German architecture bustled with tourist life. Read more »

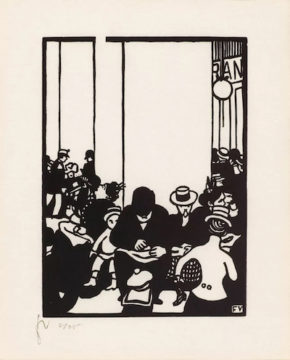

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything.

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything. Sughra Raza. At Totem Farm, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. At Totem Farm, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Shredder Self-portrait, NYC, August 2023.

Sughra Raza. Shredder Self-portrait, NYC, August 2023.