by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Like other parents, we were delighted when our daughter started walking a few months ago. But just like other parents, it’s not possible to remember when she went from scooting to crawling to speed-walking for a few steps before becoming unsteady again to steady walking. It’s not possible because no such sudden moment exists in time. Like most other developmental milestones, walking lies on a continuum, and although the rate at which walking in a baby develops is uneven, it still happens along a continuous trajectory, going from being just one component of a locomotion toolkit to being the dominant one.

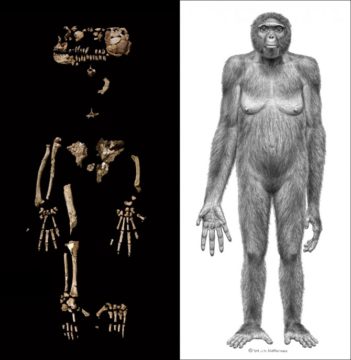

As paleoanthropologist and anatomist Jeremy DeSilva describes in his book “First Steps“, this gradual transition mirrors our species’s evolution toward becoming the upright ape. Just like most other human faculties, it was on a continuum. DeSilva’s book is a meditation on the how, the when and the why of that signature human quality of bipedalism, which along with cooking, big brains, hairlessness and language has to be considered one of the great evolutionary innovations in our long history. Describing the myriad ins and outs of various hominid fossils and their bony structures, DeSilva tells us how occasional walking in trees was an adaptation that developed as early as 15 million years ago, long before humans and chimps split off about 6 million years ago. In fact one striking theory that DeSilva describes blunts the familiar, popular picture of the transition from knuckle-walking ape to confident upright human (sometimes followed by hunched form over computer) that lines the walls of classrooms and museums; according to this theory, rather than knuckle-walking transitioning to bipedalism, knuckle-walking in fact came after a primitive form of bipedalism on trees developed millions of years earlier. Read more »