by Dwight Furrow

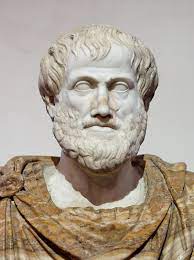

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Is there an insight here to be salvaged? Can this implausible argument about the glorious lives of metaphysicians be separated from the rest of Aristotle’s argument that philosophy is not only a way of life but the quintessentially superior way of life?

Aristotle argued that the activity of all beings is governed by their characteristic function which drives developmental processes. Reason is the characteristic function of human beings, and it’s the perfection of our capacity to reason so that we come to know the truth about a subject matter that constitutes flourishing. All human activity is directed toward this goal of flourishing although most human beings haven’t grasped its true nature or lack the necessary habits and self-control to achieve it. Thus, our pursuit of it is confused.

The study of metaphysics is the perfection of reason, on Aristotle’s view, because the object of the inquiry is permanent and the ultimate source of all order. The master of theoretical reason has a full and correct understanding of the objects that are highest by nature—divine and eternal agents of the inherent harmony of the universe and the first principles that determine that harmony. God is the ultimate source of order and thus the contemplation of God’s activity of creating and preserving order is the highest form of reason. (Aristotle thinks of God as the prime mover, the origin of all motion and development.)

Knowledge of human affairs is of secondary importance because the order exhibited by human-centered values is derived from more fundamental principles embedded in the structure of reality. It should be noted that the metaphysician who ignores ethical theory or lacks practical wisdom is not supremely happy. A thorough knowledge of practical wisdom and its embodiment in the practice of moral virtue is a necessary condition for a well-lived life. But Aristotle thought only the metaphysician would grasp the theoretical foundation of a well-lived life in the basic structure of reality. We can give ultimate reasons for the nature of human happiness only when we have understood how human lives are embedded in the system of final causes and foundational principles that govern the universe—hence the importance of metaphysics.

That’s the basic argument. Where does it go wrong?

Aristotle seems to have thought that the perfection and finality of the object of thought confers perfection on the thinker of such thoughts, an illicit inference that has little support. However, the more fundamental problem with Aristotle’s metaphysics is that the foundational principles appear to be false. Although the idea of a teleological end is useful in explaining some human and animal behaviors, the idea of a system of ultimate, final causes—the goals toward which the universe strives—plays no role in evolutionary theory and certainly no role in contemporary physics or cosmology. Furthermore, while arguments for moral realism have some currency, it isn’t clear how to make sense of the idea that nature consists of a fixed hierarchy of values or that values are a candidate for what counts as “permanent things.”

In fact, the study of metaphysics today yields no settled, secure account of the basic structure of the universe that would count as uncontroversially true. We may know lots of truths, and we now have a sophisticated science to help us think about the nature of reality, but any account of how those truths hang together in a comprehensive account of reality is little more than well-informed speculation.

But this complicates Aristotle’s approach to philosophy as a way of life. If it is the possession of truth that makes philosophy the primary instance of a life well-lived, then philosophy would fail to satisfy that standard. Philosophy is a landscape of competing, incompatible theories underdetermined by ambiguous evidence. As much as we may value the pursuit of truth, we seldom find it. At best, we may, over the centuries, make incremental progress toward the truth. Thus, if philosophy contributes to a well-lived life, it is the pursuit of truth, not having it, that is of value.

Given the uncertainties regarding metaphysical truths, does metaphysics then have any practical value? Or should we join the end-of-metaphysics chorus that has dominated much recent philosophy?

Post-Darwinian biology, social science, and far-from-equilibrium physics suggest a universe of continuous, unpredictable change. The laws of physics may be relatively stable, although many doubt this, but it does not follow that the entities we encounter and the conceptual categories we use to understand them are stable.

Whether one is a partisan of Derrida, Wittgenstein, the pragmatists, Deleuze, Whitehead, or the various iterations of historicism, they all share the notion that conceptual categories are conditioned not by apriori structures of thought but by actual empirical relations that exist only contingently. A change in those relations shifts the boundaries of the worlds we occupy and the conceptual categories needed to grasp them, boundaries that are always escaping our capacity for representation because relations are unstable—a contingent matter of what happens next that is not only unpredictable but often cannot be grasped without fundamental conceptual change. If elements are a function of relations and different relations entail different elements, then the identities of what we encounter in life need to be continuously re-constituted given the underlying changes in relations.

Apples have relatively stable features and differ from oranges. But if apples are used differently, grown differently, or genetically modified they might come to resemble oranges.

Many have argued that this signals the end of metaphysics because the attempt to represent the whole via a system of fixed categories is futile. But I think a different conclusion is warranted. My suggestion is that ontology is not the study of what exists but of what emerges, and what emerges is a product of how we live. We are all (unthinking) ontologists because of the choices we make. Look around you at the objects and processes that populate our lives. Think in detail about what it means to be an active, engaged person in the 21st century. Most of it wasn’t imaginable 100 years ago let alone 2500 years ago. What it means to be human today is only contingently related to what it meant for Aristotle—a collection of similarities and differences with highly contested, multiple, through-lines.

Ontology is a valuable inquiry because it tracks the emergence of entities that force conceptual revision. No ontology could be complete because we don’t know ahead of time what beings are capable of since their capacities are dependent on those shifting, unpredictable relations as well. This includes science. We can think of atoms and molecules as basic, stable elements, but we don’t know what they can do without what John Dewey called “experiments in living.” Laws of nature may be relatively stable. But our understanding is always provisional because those laws function differently in various contexts many of which haven’t yet been discovered.

Thus, the concepts recently developed in the critique of metaphysics—Wittgenstein’s language games, Derrida’s Différance, Heidegger’s Ereignis, Deleuze’s assemblages—are not timeless concepts positioned outside of history but attempts to capture something new emerging in humanity’s self-understanding.

What is valuable about tracking emergence? Does this influence the argument for the glorious life of a metaphysician that Aristotle advanced? Modern metaphysics suggests that we live in a world of constant change with uncertainty a palpable presence. False closure and a sense of certainty puts us out of tune with the worlds we inhabit. Unfortunately, to be aware of the flux of reality doesn’t lead to feelings of happiness. Too often, it’s the false certainties that provide comfort.

But to be left behind when your world changes is among the greatest threats to well-being. If the music never stops, there is much to be said for learning how to dance.

For more on philosophy as a way of life visit Philosophy: A Way of Life