by Gus Mitchell

(Read Pt. 1)

If there has been a decline in many parts of our culture in the last several years, and if we are increasingly bored by the infinitude of content offered us in exchange, then the blurring of art and content has a lot to do with it.

Increasingly, both societally and culturally, we can process only information, or as Mark Zuckerberg put it, via “information flow.” In the world of culture, this translates to awards, lists and listings, rankings, ratings, returns, engagement, traffic, clicks, likes, shares, subscriptions, metrics, algorithms, data, numbers. Mass culture is now nothing other than the content we feed into this nexus of informational processing.

But only imagination can transfigure information, reify it, make us feel it, make it mean or do something.

To return to that etymological ramble from last time, content in adjectival form is a feeling of a “fullness”, that feeling which Shakespeare associated with the “heart’s content.” But content, in this sense, and capitalism, are incompatible. In Capitalism and Desire, Todd McGowan writes that “those who are not continually seeking new objects of desire”, or those who “content themselves with outmoded objects and recognize the satisfaction embodied in the object’s failure to realize their desire…are not good consumers or producers” of the commodities that capitalism produces to fill the sense of emptiness it inculcates. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me.

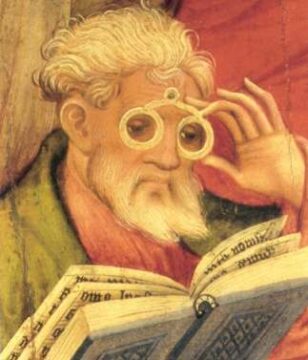

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me. I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is.

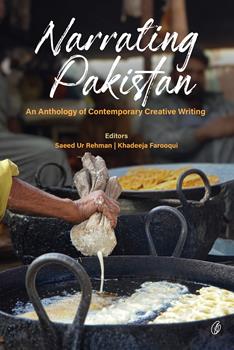

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is. Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.

Andrew Torba, Christian Nationalist founder of the rightwing social media site Gab, recently argued on his podcast that the fact that many of the most beloved Christmas songs were written by Jewish composers was part of a conspiracy to take Christ out of Christmas: to secularize one of the holiest Christian holidays and allow Jews to subtly infiltrate Christian-American culture with their own agenda. He might just be right.

Andrew Torba, Christian Nationalist founder of the rightwing social media site Gab, recently argued on his podcast that the fact that many of the most beloved Christmas songs were written by Jewish composers was part of a conspiracy to take Christ out of Christmas: to secularize one of the holiest Christian holidays and allow Jews to subtly infiltrate Christian-American culture with their own agenda. He might just be right.