by Ashutosh Jogalekar

I loved chemistry so deeply that I automatically now respond when people want to know how to interest people in science by saying, “Teach them elementary chemistry”. Compared to physics it starts right in the heart of things. —Robert Oppenheimer

How much science can you teach very young children? I have been exploring this question for the past one year or so as I experiment with teaching various kinds of scientific topics to my 3-year-old daughter. She has been generally quite receptive and curious about everything I tell her, and whatever I have failed to teach her is largely a reflection on either the intrinsic difficulties of explaining certain kinds of ideas or my own communication skills.

Chemistry has always been more accessible than physics to laymen, largely because of its colors and explosions and smells and relevance to everyday life; it “starts right in the heart of things”, as Oppenheimer put it. But even at an elemental level it seems easier because of the architectural nature of the subject – atoms which are the building blocks assemble into larger molecules. The basic idea to communicate was to think of atoms as balls that can attach to different numbers of other balls based on what element they represent – one for hydrogen, two for oxygen, three for nitrogen, four for carbon and so on. The combination of atoms into molecules then becomes a simple exercise — just count whether each atom attaches to its right number of neighbors. To make it friendlier, I asked my daughter to see if each atom has the right number of “friends” it holds hands with. Read more »

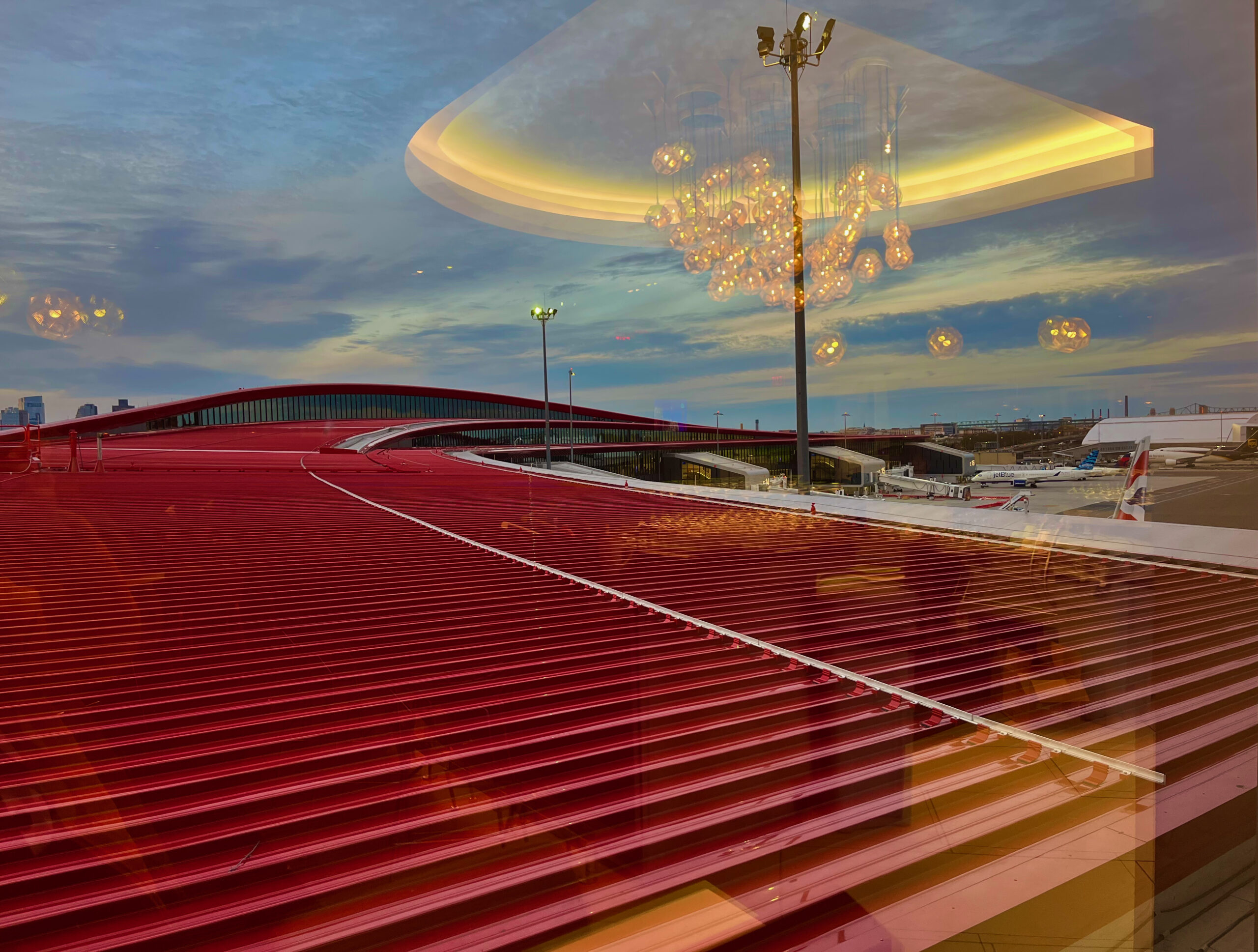

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III.

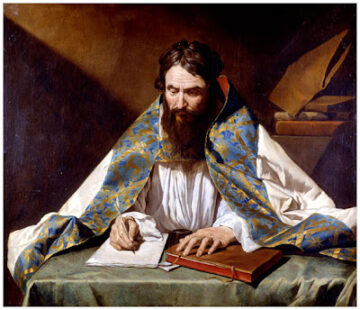

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III. As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

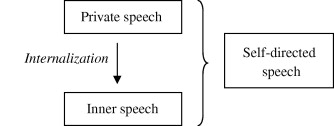

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

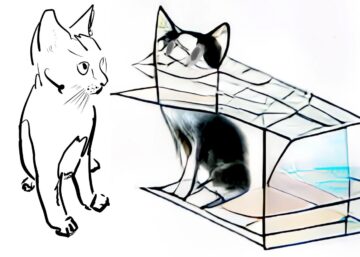

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.

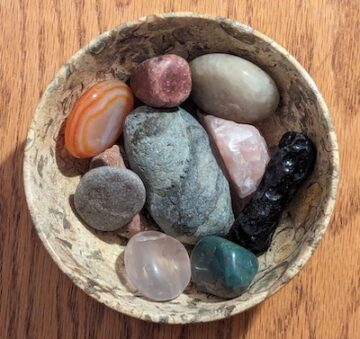

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made. I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones.

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones. Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.

Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.