A painting at the Löwenhof Hotel in Vahrn, South Tyrol.

When Time Stands Still

by Raji Jayaraman

Vijay was the smartest kid in class. It was a small class, and we weren’t especially bright, but I don’t mean that he was smart in a big-fish-small-pond sense. I mean it in absolute terms. He was a math genius. Short and slight of build there was nothing remarkable about his appearance, at least not neck-down. Neck-up, it was a different story. He had a massive head and we’re talking Boss Baby proportions. On anyone else, that head would have been fair game for mockery. But perched on Vijay’s shoulders, with a brain that size, it seemed like the only feasible design choice.

The boarding school we attended wasn’t especially prestigious. It wasn’t Mayo or Doon, where blue-blooded Indians waitlisted unborn children who, by accident of birth, were predestined to rule. No, the currency for admission wasn’t pedigree. It was money. There were three groups of students who could afford to attend our school. The first was rich kids, whose parents paid out of pocket. Some belonged to the petty nobility who, despite the half-century old abolition of titles, had managed to retain some ancestral wealth. Theirs was old money. It was solid, with no need for external trappings. Indeed, their lack of pretension was so flagrant it bordered on deceit. In middle school, for instance, we had to cancel our third and final run of “You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown” because one of the lead actors’ fathers, L.’s dad, died. As the eldest son, L. had to go home to perform his father’s final rites. Snoopy never returned to school because he was now the Raja of P.

The new money was different. They had generous monthly allowances and wore designer clothes with fancy French names I couldn’t pronounce: Es-spirit, Die-ore, Gukki. Many of these kids belonged to families who, by hook or crook, had secured state monopolies in key industries of India’s post-independence “licence-Raj”. Others were expatriates whose parents worked in Indian joint ventures, or belonged to well heeled families from neighbouring countries. Read more »

Monday, January 1, 2024

A World Unsettled: The Supreme Court And The Risks Of Activism

by Michael Liss

January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well.

January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well.

The New Year is often about taking stock, and if I’m counting correctly, this is my 101st essay for 3 Quarks Daily. The majority have been about American history, American politics, and what is ostensibly American law but looks a lot like politics.

Last August, as the 49th anniversary of Richard Nixon’s resignation drew near, I started a series about the chaos of the late 1960s/early 1970s and how Presidents can lose their hold on the White House. That led me back to two men, one famous, the second memorable, who, to this day, in different ways, have had an impact on the way I think.

I will come to Henry Kissinger shortly, but I first want to spend a little time celebrating Walter Kaufmann. This is not the prolific philosopher Walter A. Kaufmann who was a pre-World-War-II expat from Germany, got his PhD at Harvard, and spent most of his career at Princeton. My Walter Kaufmann is Walter H. Kaufmann, who was also a German expat, got his PhD at the New School for Social Research, and, in 1953, published Monarchism in the Weimar Republic. My Dr. Kaufmann liked a cigar, a good story, and a better glass of wine. He also taught at my high school—German to those less linguistically challenged than I was, AP European History to voluble (in English) types like me. Dr. Kaufmann had a certain cool about him, in no small part for having gone to grade school with Werner Klemperer, son of the conductor Otto Klemperer, and, to Dr. K’s enduring dismay, the future Colonel Klink.

Like all good little suburban students, we took AP classes to take AP exams to score high enough to get college credits. Dr. K was a realist, but wanted to teach this subject on his terms. The word went out that no one got higher than a 93, his logic being that no one could know anywhere near 100% of the subject matter. So, if you were in the running for Valedictorian or Salutatorian and/or cared very much about your final class rank, to learn at the feet of Dr. K came with some obvious risks. Read more »

The Posthumous Trials of Robert A. Millikan

by David Kordahl

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when the picture was taken. But public memory is fickle, and today only the man on the right is still recognizable to most people.

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when the picture was taken. But public memory is fickle, and today only the man on the right is still recognizable to most people.

Albert Einstein, Time Magazine’s “Man of the Century,” the father of special and general relativity, has a place in science that remains secure, regardless of what one thinks of his life as a whole. Despite activist efforts at demystification, Einstein the scientist is unblemished by any misgivings about his personal life or political activities. Robert A. Millikan, the bow-tied man on the left, is far less secure. The posthumous charges against Millikan have been against his scientific integrity and his political sympathies, and his detractors have made headway.

In 2020, Pomona College changed the name of their Robert A. Millikan Laboratory, noting Millikan’s “history of eugenics promotion,” along with his purported sexism and racism. In 2021, the California Institute of Technology, the institution that Millikan spent decades building, followed suit, renaming Millikan Hall as Caltech Hall, and discontinuing the Millikan Medal, previously the Institute’s highest honor. Citing Caltech’s precedent, the American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) renamed its own Millikan Medal later that same year.

Since I spend most of my time teaching physics, and since I am myself a member of the AAPT, it was the last of these name changes that rankled me the most. These allegations bothered me because I suspected that they weren’t quite fair. Read more »

Theodicy. The Idiocy.

by Rafaël Newman

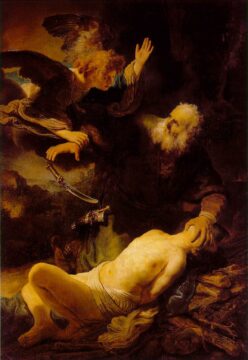

There was an old man who so loved his son,

His day was only properly begun

Once he had hugged his darling to his breast

And kissed his tender cheek. Nor could he rest

At night until the boy was put to bed;

And still he’d stand by him, and stroke his head.

Or let’s just say: he liked him well enough,

Could bear his cries, and was not over-rough

When scolding him, begrudged him not his meat,

And saw that he had leather on his feet.

No, it was worse: in truth, he hated him,

Became a father on a drunken whim

And now was bound by duty, not by joy,

To spend his dotage tending to the boy.

The point is—love, or loathe, or suffer him,

That man prepared to carve him limb from limb

In answer to the urging of a voice

Within his head, which offered him a choice:

Prove your compliance with a sacrifice,

Or be excluded from my paradise.

It didn’t come to that, of course. The child

Was spared—not by his father, who was wild

To do the will of his delirium,

But by the very same mysterium

That had decreed the awful liturgy,

Which very act proved it a deity:

Inscrutable, contrarian, perverse—

A fitting ruler of the universe. Read more »

Once More Around the Sun, then Home

by Akim Reinhardt

We’re circling the Sun at a rate of between 18.20–18.83 miles per second. It is not a fixed speed because Earth travels on an ellipsis, and moves a hair faster when it’s closer to the Sun than it does when further away. It averages out to about 67,000 miles per hour over the course of the year. At that speed, a full revolution is 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 46 seconds in the making. At least for now.

Each year, Earth’s voyage around the Sun takes just a little bit longer, to the tune of roughly 3 nanometers per second. It’s minuscule, but adds up over time. Since the solar system’s inception 4.571 billion years ago, Earth is moving 22 mph slower.

The main reason is that Earth is drifting ever so slightly away from the Sun, stretching out the orbital path, and lengthening the duration of a revolution.

We’re not fleeing the Sun so much as it’s pushing us away. As the Sun’s hydrogen core transmogrifies into helium through the process of nuclear fusion, the Sun loses somewhere in the neighborhood of 4 million tons of mass every second. Since that process began billions of years ago, the Sun has lost mass equivalent to 1 Saturn, or approximately 95 Earths if you prefer to think about it in homier terms. The Sun also suffers particle loss through Solar Wind, and that has resulted in its shrinking by another 30 Earths or so. Solar flares and coronal mass ejections also steal away mass. In all, the Sun is ~1027 kg lighter than it was at the birth of our Solar System. Here’s what 1027 looks like written out in digits:

1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

Since a ton equals two-thousand, feel free to add another three zeroes and flip that one to a two. Then again, a gram ain’t much, so maybe just leave it as is, stare at it a bit, and try to feel the full weight of it. Read more »

Wordkeys: Content (Scattered Crumbs Of A Unified Theory, Part 2)

by Gus Mitchell

(Read Pt. 1)

If there has been a decline in many parts of our culture in the last several years, and if we are increasingly bored by the infinitude of content offered us in exchange, then the blurring of art and content has a lot to do with it.

Increasingly, both societally and culturally, we can process only information, or as Mark Zuckerberg put it, via “information flow.” In the world of culture, this translates to awards, lists and listings, rankings, ratings, returns, engagement, traffic, clicks, likes, shares, subscriptions, metrics, algorithms, data, numbers. Mass culture is now nothing other than the content we feed into this nexus of informational processing.

But only imagination can transfigure information, reify it, make us feel it, make it mean or do something.

To return to that etymological ramble from last time, content in adjectival form is a feeling of a “fullness”, that feeling which Shakespeare associated with the “heart’s content.” But content, in this sense, and capitalism, are incompatible. In Capitalism and Desire, Todd McGowan writes that “those who are not continually seeking new objects of desire”, or those who “content themselves with outmoded objects and recognize the satisfaction embodied in the object’s failure to realize their desire…are not good consumers or producers” of the commodities that capitalism produces to fill the sense of emptiness it inculcates. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Digital photograph February 2022.

A Fruitful Exploration of the Core

by Marie Snyder

Maybe there are seeds of potential deep within ourselves, but maybe there’s nothing there but a collection of signals. Regardless the outcome, we need to dig in to see what we can find.

In several classes I took last term, the idea of a core self that’s fluid came through discussions of the postmodernist view of the self. But I’m not convinced we’re still living the pomo life, and I’m not sure we want to be.

Taking liberally from Charles Taylor, and others, it appears that we once had some communal ideals, then flipped from seeking answers from God to proving them with science, then realized some pretty major problems with glorifying any kind of authority and renounced all of them, but now, drawing on the types of films being made and the stories told, it feels like we’re readjusting back to a place with more solid values and truths. I hope so, anyway.

In the pre-modern time, when God was truth and miracles could happen, there was no need for individual identities. We were all divine through our very creation. Modernism reacted against random beliefs with a scientific method that began to be embraced to find the real truths out there. Suddenly individual identity became interesting. What even are we? In 1641 Descartes deduced we have proof that we exist whenever we consider our own existence because something must be there to be thinking about what we are, and we call that something “I”. That was a big deal. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Un Americano in Arabia

by David Winner

“Forget skyscrapers, ice water, drinks, stockmakers, New York, half chewed cigars, and statues of liberty. Think of camel bells, cyclamen and the last lions,” wrote Bill Barker, the commander of the northern province of mandate Palestine to his lover, my great Aunt Dorle in 1934, trying to encourage her to move from New York to the Middle East. Dorle was entrenched in the New York music world by that point, working with the New York Philharmonic, but she had grown up a poor little rich girl from New York inspired by the tales of Scheherazade. The Middle East was an enchanted place and Islam its enchanted religion.

But when I think of her travels in the Arab world in the twenties and thirties, it is nineteenth century composer and part time Orientalist Gioachino Rossini who comes to mind: his operas about traveling from the east to the west and visa-versa: Un Italiano in Algeria, Un Turco in Italia. What would he have called Dorle, Una Fanciulla (young girl) Hebraica in Arabia?

Certainly, Dorle’s vision of The Orient had not progressed far beyond Rossini’s. Georges Asfar, another lover in her prolific thirties (a Syrian Christian) encouraged her to think of him as her Muslim master. Like Barker, he littered his letters with Arabic, the magical language of magical places.

I’ve carried something of that flame myself the few times I’ve traveled in the Arab world, but worse than my muted Orientalism, I’ve sometimes fallen prey to an even more dangerous trope, represented by Claire Danes as Carrie from Homeland, her blond hair disguised by a hijab, walking purposefully through devious Muslim spaces.

However sophisticated and well-traveled I see myself, I’ve fallen into sinkholes of fear and prejudice while traveling in what Dorle would have called the Orient. Read more »

Monday Photo

Some Scattered Thoughts about Maestro, Music, and the Meaning of It All

I’ve now seen Maestro twice, spread out over four, maybe five, sittings. I suppose the fact that I haven’t watched it straight through in a single sitting might be taken as an indication that I didn’t find it…Didn’t find it what? Good, compelling, interesting, satisfying? If one or some combination of those is true, then why did I watch it twice? Maybe I found it disturbing and wanted to figure out what was bugging me? If it was disturbing, the disturbance was unconscious.

[That I didn’t watch the whole film in a single sitting is certainly an indication of the fact that I watched the film at home, in front of a small screen, instead of in a theater and with a large audience.]

Was I bugged? Yes, I was bugged, about the damned prosthetic nose. I kept reading that Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic offended some people. Bernstein’s kids defended it. There I am, watching the film. There’s the second scene where Bernstein is seated, gray hair, red shirt, smoking a cigarette, and talking about his (dead) wife. He had an intense almost vibrant tan, a color looking like it didn’t quite make the cut for Rudolph’s nose. Did he hang out in a tanning booth? That bugged me, a little.

I don’t know whether or not I’d have been bugged about the nose if I hadn’t heard so much about it. I never saw Bernstein live, but I certainly saw him on TV and saw lots of photos. As far as I recall I never gave two thoughts to his nose.

Now my father, he had a nose. We called it a Danish nose because his parents were from Denmark. Which was bigger, my father’s Danish nose, Bernstein’s (Jewish) nose, or Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic version of Bernstein’s (Jewish) nose? This is silly.

I wonder if all this fuss about a schnoz is part of the shadow cast by the awful events of October 7th? Or the resurgence of antisemitism in the country? Did I know that Bernstein was Jewish the first time I became aware of him, perhaps from one of those Young People’s Concerts on TV or perhaps it was a more straightforwardly didactic program? I’m pretty sure I knew Louis Armstrong was black the first time I became aware of him. Couldn’t miss it. The color of his skin was as plain as the four-letter-word on your face. Read more »

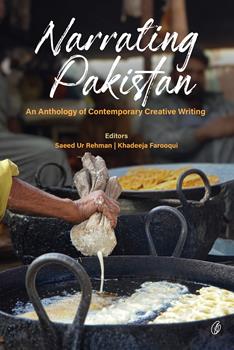

In Defense of the MFA: A Review of “Narrating Pakistan”

by Sauleha Kamal

Narrating Pakistan: An Anthology of Contemporary Creative Writing sets a lofty aim for itself: “to explore the idea of Pakistan through contemporary stories—the term, the country, the nation, the identity…”. There have been a few attempts to anthologize Pakistan in the past few decades. Oxford University Press anthologies like I’ll Find My Way (2014), Muneeza Shamsie’s two collections (which the preface to this book mentions), Granta 112: Pakistan (2011) and, as far as academic explorations of Pakistan go, The Routledge Companion to Pakistani Anglophone Writing come to mind. Ultimately, this anthology sets itself apart by telling, not the story of Pakistan but the story of young Pakistan. The characters in these stories are often young people—children, teenagers and young adults—dealing with the trauma of confronting what is, what could have been and what will be. This anthology brings together various writers who write about everything from dreaming of casting off economic shackles—in small villages, giant metropolises and foreign cities that glitter with promise and danger—to confronting isolation—following the Coronavirus pandemic, immigration or a depressive episode. There are stories that explore humanity through the loneliness of the female experience in a patriarchal milieu and the difficulties of conceptualizing Muslim masculinity in post-9/11 America.

Narrating Pakistan: An Anthology of Contemporary Creative Writing sets a lofty aim for itself: “to explore the idea of Pakistan through contemporary stories—the term, the country, the nation, the identity…”. There have been a few attempts to anthologize Pakistan in the past few decades. Oxford University Press anthologies like I’ll Find My Way (2014), Muneeza Shamsie’s two collections (which the preface to this book mentions), Granta 112: Pakistan (2011) and, as far as academic explorations of Pakistan go, The Routledge Companion to Pakistani Anglophone Writing come to mind. Ultimately, this anthology sets itself apart by telling, not the story of Pakistan but the story of young Pakistan. The characters in these stories are often young people—children, teenagers and young adults—dealing with the trauma of confronting what is, what could have been and what will be. This anthology brings together various writers who write about everything from dreaming of casting off economic shackles—in small villages, giant metropolises and foreign cities that glitter with promise and danger—to confronting isolation—following the Coronavirus pandemic, immigration or a depressive episode. There are stories that explore humanity through the loneliness of the female experience in a patriarchal milieu and the difficulties of conceptualizing Muslim masculinity in post-9/11 America.

A story about young Pakistan today cannot be told without telling the story of leaving Pakistan, as more and more young Pakistanis do every year. Many of the stories in this anthology are about the consequences of leaving and the challenges of diasporic existence. Many of these stories deal with the alienation of being a person of color in places that are not too kind to people with the wrong skin color, to paraphrase the wording of multiple stories. The idea of the wrongness of an “epidermis” crops up in both Syed Kazim Ali Kazmi’s “Trans/Gress” and Saeed Ur Rehman’s “The Sharpness of Grass Blades”. The narrator in Aatif Rashid’s “Brown Mirror” yearns to peel off his brown skin. Read more »

Monday, December 25, 2023

A Mysterious Encounter: The Owl on the Bench

by David Greer Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me.

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me.

Not in the flesh, of course. Instead, I received a visit from a creature whose behavior was so unexpected, so unnerving, so uplifting, that it seemed to defy rational explanation, and I felt the presence of my wife as strongly as if she were beside me.

The visitor was a barred owl. I’m familiar with barred owls, though not with barred owls as familiars. At night, I’ve often heard from the forest the signature barred owl query, “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?” Less often, I’ve been jolted awake by a bloodcurdling scream–is someone’s throat being cut?—and my heart pounds until reason clears the fog from my brain: it’s only an owl. I’ve also on occasion gone into the forest to investigate strange querulous whistles that become less strange when I spot a trio of juvenile barred owls begging a parent for food—a freshly killed fieldmouse or flycatcher—and counting on persistent whistling to do the trick.

But the owl that visited me after my wife’s death was silent. She sat outside the door, perched on the back of the garden bench on which my wife had loved to sit after walking unaided became too difficult for her. (I say ‘she’ because female barred owls are up to a third larger than males, and this was a very large owl.) There was no missing her. Barred owls are not unobtrusive. They’re smaller than a great horned owl but considerably larger than the northern spotted owl, whose habitat they have been taking over since first being observed in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s. Their gradual spread west from their native habitat in eastern North America may have been enabled by the reforestation of parts of the prairie after the age-old indigenous practice of burning grasslands was prohibited. Read more »

Ed Simon’s Twelve Months of Reading – 2023

by Ed Simon

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

“A strong and bitter book-sickness floods one’s soul,” writes Nicholas Basbanes in A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books. “How ignominious to be strapped to this ponderous mass of paper, print, and dead men’s sentiments!” My books sit two levels deep on the de rigueur millennial’s sagging white IKEA BILLY shelves, the planks having lost their dowls while buckling underneath the weight, titles creatively pushed into any absence that they can credibly fill. There are cairns of books on my office floor, megaliths of books along my windowsill, ziggurats of books in the mudroom, the basement, the attic. A whole shelf of Penguin Classics, their zebra-colored spines announcing themselves – Castiglione’s The Book of Courtier, Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil. Sprinkled throughout the rest are an assortment of Oxford World Classics, Library of America editions, Nortons. There are other classics – The Aeneid, Moby-Dick, et el. There are contemporary works – Portnoy’s Complaint, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Categories for reference and poetry, academic and journalistic. Then there is the disposable that I’ve held onto (too polite to name names). Naturally, the question posed to me by any visitor who isn’t a bibliophile (though predictably I know few of that sort) is if I’ve read all of these books. My reply, as close to a joke as I can muster about the affliction, is that I’ve at least opened all of them. I think. Read more »

Monday Poem

https://genius.com/Christmas-songs-the-twelve-days-of…

________________________________________

Twelve Days of Christmas and Other Mysteries

—what must I have missed?

—

sunlight blushed with red —hiding? Could be.

today will surely know where a partridge lives,

not to mention how a partridge loves or beds.

—

—at least this is what the lyric tells.

—

Terrible AI Arguments (and, No, AIs Will Not be Recursively Self-Improving on Computer-Like Time Scales)

by Tim Sommers

(The butter robot realizing the sole purpose of its existence is to pass the butter.)

In the halcyon days of “self-driving cars are six months away,” you probably encountered this argument. “If self-driving cars work, they will be safer than cars driven by humans.” Sure. If, by “they work,” you mean that, among other things, they are safer than cars driven by humans, then, it follows, that they will be safer than cars driven by humans, if they work. That’s called begging the question. Unfortunately, the tech world has more than it’s share of such sophistries. AI, especially.

Exhibit #1

In a recent issue of The New Yorker, in an article linked to on 3 Quarks Daily, Geoffrey Hinton, the “Godfather of AI,” tells Joshua Rothman:

“‘People say, [of Large Language Models like ChatGPT that] It’s just glorified autocomplete…Now, let’s analyze that…Suppose you want to be really good at predicting the next word. If you want to be really good, you have to understand what’s being said. That’s the only way. So, by training something to be really good at predicting the next word, you’re actually forcing it to understand. Yes, it’s ‘autocomplete’—but you didn’t think through what it means to have a really good autocomplete.’ Hinton thinks that ‘large language models,’ such as GPT, which powers OpenAI’s chatbots, can comprehend the meanings of words and ideas.”

This is a morass of terrible reasoning. But before we even get into it, I have to say that thinking that an algorithm that works by calculating the odds of what the next word in a sentence will be “can comprehend the meanings of words and ideas” is a reductio ad absurdum of the rest. (In fairness, Rothman attributes that view to Hinton, but doesn’t quote him as saying that, so maybe that’s not really Rothman’s position. But it seems to be.)

Hinton says “training something to be really good at predicting the next word, you’re actually forcing it to understand.” There’s no support for the claim that the only way to be good at predicting the next word in a sentence is to understand what is being said. LMMs prove that, they don’t undermine it. Further, if anything, prior experience suggests the opposite. Calculators are not better at math than most people because they “understand” numbers. Read more »

Aristotle and the Pleasures of the Table

by Dwight Furrow

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is.

It might strike you as odd, if not thoroughly antiquarian, to reach back to Aristotle to understand gastronomic pleasure. Haven’t we made progress on the nature of pleasure over the past 2500 years? Well, yes and no. The philosophical debate about the nature of pleasure, with its characteristic ambiguities and uncertainties, persists often along lines developed by the ancients. But we now have robust neurophysiological data about pleasure, which thus far has increased the number of hypotheses without settling the question of what exactly pleasure is.

Part of the problem is that we have this word “pleasure” that seems to apply to any positive affective state, and we therefore think there must be something common to all the diverse experiences designated by the word. But that unity may be an illusion. There is a vast experiential difference between the pleasures of basking in the sun and the pleasure one experiences from having run a marathon. I doubt that Aristotle’s theory can explain the former; the latter seems more amenable to his focus on activities which would include the pleasures of the table. And so I will set aside attempts to define pleasure in general and focus on the pleasure we take in our activities, specifically the activity of eating. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Praise of Shadows. Shalimar Bagh, Lahore, December 10, 2023.

Digital photograph.