by Barbara Fischkin

In 1919, after a brutal anti-Semitic pogrom in a small Eastern European shtetl, my grandfather knew that his wife and three young children would be better off as refugees. He prepared them to trek by foot and in horse-drawn carts from Ukraine to the English Channel and eventually to a Scottish port. Finally they sailed in steerage class to the United States. My grandfather was a simple watchmaker—and one of the visionaries of his time. Europe, he told his tearful wife, was not finished with murdering Jews, adding that things were likely to get much worse. And so, my grandmother became a hero, too. She said farewell to her mother and sister, knowing she would never see them again. In Scotland, she descended to the lower level of a ship with her children—my mother, the eldest, was seven years old. My grandmother traveled alone with her children. My grandfather was refused entry to the ship. He had lice in his hair. He arrived in the United States weeks, or possibly months, later.

My grandfather, Ayzie Zygal of Felshtin, Ukraine became Isaac Siegel of Brooklyn, New York, where he lived for the rest of his life. In his later years he spent summers in the Catskill Mountains, always asking to be let out of the family car a mile before reaching Hilltop House, a bungalow colony. My grandfather wanted to walk that last mile along the local creek. It reminded him of the River Felshtin. He never regretted coming to America.

My grandparents died, in Brooklyn in their early sixties. My grandfather had been poisoned by the radium he used on the paint brushes in his shop to make the hours glow. He licked them, with panache, to make them sharper. My grandmother had a heart condition, exacerbated by diabetes. They were both gone before I turned three.

They had lived much longer than they had expected they would in 1919.

I was told my grandfather left Europe to save his family’s life. And because my mother narrowly escaped death. I was told he did not believe there would be any more miracles. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023. The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

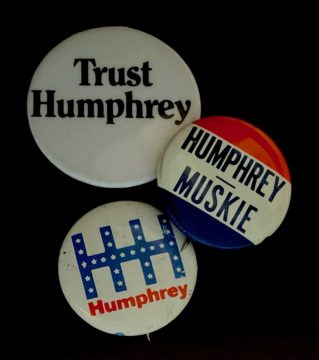

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons. I teach at a large, public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. For about a decade now, the upper administration has had a habit of sending “comforting” emails whenever there’s a major school shooting. Of course there are far too many school shootings in America to send a note for each one, so I suppose the administration tries to keep it “relevant,” for lack of a better word. These heartfelt missives arrive in my Inbox once or twice a year, typically after some lunatic shoots up a college campus. So far as I can tell, they go to everyone. To every faculty member, staff member, and student on campus. To 25,000 people or more.

I teach at a large, public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. For about a decade now, the upper administration has had a habit of sending “comforting” emails whenever there’s a major school shooting. Of course there are far too many school shootings in America to send a note for each one, so I suppose the administration tries to keep it “relevant,” for lack of a better word. These heartfelt missives arrive in my Inbox once or twice a year, typically after some lunatic shoots up a college campus. So far as I can tell, they go to everyone. To every faculty member, staff member, and student on campus. To 25,000 people or more.