A Conversation between Andrea Scrima and Anike Joyce Sadiq

The following conversation took place from November 2021 to February 2022 via e-mail in reaction to a general meeting of the Villa Romana Association that took place on October 28, 2021 in Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin. The authors participated in this meeting in their function as members, having been actively involved for two years in a group of artists that had formed in response to a new funding situation. When there was no longer any way to prevent a simultaneous changeover in directors, the group sought to at least preserve the Villa Romana as a place created by artists for artists and to ensure that the general direction of the program established under Angelika Stepken be continued.

The Villa Romana was founded in 1905 as a German art association in Florence. In addition to an exhibition program and numerous collaborations with artists as well as with art and cultural institutions both local and international, the Villa Romana Prize is awarded each year to four artists or collectives from Germany in the form of a ten-month residency and grant.

This conversation attempts, from the authors’ perspective, to reconstruct, contextualize, and archive the discussions that occurred between artist members and the board and the course these took over time. It poses questions about membership and the extent of agency it allows, and inquires into the role artists play in shaping institutional structures. Financial and political dependencies, the seeming openness of a diversity-based policy toward art and culture, and the (re)distribution of the real and symbolic capital that becomes legitimized by a non-profit status are subjects of investigation.

Anike Joyce Sadiq:

I became a member of the Villa Romana Association in 2018, just as Deutsche Bank was planning to terminate or significantly reduce their support of the Villa Romana in Florence, which they’d been funding since 1920. And the director, Angelika Stepken, was concerned that Deutsche Bank representatives would continue to hold onto their positions on the board even after they’d withdrawn their financial support. If I’ve understood its organizational form as a non-profit association correctly, the members are supposed to shape the Villa Romana as an institution. According to Angelika Stepken, there were only about 23 members in 2018, the majority of them Deutsche Bank employees; in 2018/19, around 40 artists joined. Were you one of them? When and why did you become a member?

Andrea Scrima:

I joined a little later. I submitted my request in late 2019; I didn’t get a response until mid-May of 2020, in other words, a full six months later. Little did I know that this reluctance to accept new members into the association would become a major point of contention. I did, however, know early on that Deutsche Bank was planning to withdraw their funding, and had spoken to Angelika Stepken about it. Her main concern at the time was to ensure the program’s continued independence; she had already begun looking for sources of funding in the private sector. I wanted to help in some way, and so I wrote an article about the Villa for an internal family publication, hoping to attract patrons among the more affluent branches. The amazing thing was that I got an answer pretty quickly from my partner’s cousin, whom he hadn’t seen since childhood. She had spent a lot of time in the Villa as a child, because her father was the Deutsche Bank representative responsible for the Villa Romana. It was one of those astonishing coincidences. She wrote me an emotional email, which marked the beginning of our correspondence. Her plan was to find ten private sponsors to secure a reliable annual sum for the Villa. This would have been in addition to a possible endowment Angelika Stepken was in the process of negotiating. The moment Corona hit, however, everything fell apart. But we wanted to at least convince her to run for the board, and we assumed that other financial collaborations would become possible again once the pandemic situation, which was still completely new at the time, stabilized somewhat. But she never received a response to her request to join the association, which she’d sent in November 2020—even after we brought up the matter with the Villa Romana’s board of directors several times. After five months, she finally wrote an email to tell them she was withdrawing her request.

AJS:

I find the idea of retaining independence through corporate sector funding extremely interesting. Intuitively, I’d always assumed that government funding meant greater programmatic and artistic freedom. But we have to distinguish here between funding through the State Ministry for Culture (German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, which goes by the German acronym BKM), whose task is, among other things, “to promote cultural institutions and projects of national importance,”[1] or through the Foreign Office (the Goethe Institute and the Institute for Foreign Relations). The ifa and the Goethe Institute, which is “the largest institution of foreign cultural policy”[2] in Germany, are, by definition, an extension of German foreign policy. To my mind, this becomes particularly evident as we observe the focus in their promotion of cooperative projects between particular countries and continents shifting to where a political or economic interest is at stake. Deutsche Bank always seemed to hold back in terms of thematic content, whereas Angelika Stepken, after including the Anti-Humboldt Box[3] in the 2015 “Unmapping the Renaissance” exhibition,[4] received an email from the State Ministry for Culture (BKM) objecting in no uncertain terms to her showing the work, which criticized one of the country’s largest national cultural projects—they were of the opinion that she should have informed the BKM about it in advance. I found that quite remarkable, very close to a form of censorship. It felt like a warning: evidently, there are critical issues and political attitudes that are not welcome. Even if they refrained from expressing the potential consequences. The same thing happened again later, when the Anti-Humboldt Box was presented at the Goethe Institute in Johannesburg.

I wonder how this might have played into the tensions between Angelika Stepken as the person responsible for the Villa Romana program, the artist members, and the board/BKM? Do you remember how it came about that the State Ministry for Culture (BKM) took over the major part of financing the Villa Romana?

AS:

As far as I understood it, the BKM offered early on to take over the Deutsche Bank contribution in addition to what they were already funding. Angelika Stepken wanted to avoid depending on a single source, however, and was leaning toward a public-private financing model. Particularly in that the BKM, which still had a seat on the board at the time, made it clear that the Mediterranean theme should not appear on the homepage because the Villa was funded by the BKM and not the Foreign Office. In addition to this, in 2021, the first year they took over the bulk of the funding, the BKM asked why the majority of art prize winners were of non-German origin—and stipulated that from now on, all winning artists would have to prove that they had been living in Germany for at least five years prior to their nomination. And when the crisis in Afghanistan escalated, Angelika Stepken tried—quickly and unbureaucratically—to grant seven professors from the Herat Art Academy who feared for their lives refuge at the Villa Romana; her appeal to the BKM, which they only got around to answering a week later—they had been, as they explained, “on vacation”—was rejected due to “a lack of management prototype” and the required coordination with the Foreign Office.

One can debate at length which option calls for the greater willingness to compromise: corporate sponsorship or public funding, with all the bureaucracy the latter entails. Like you, I would have thought that government funding was the path to greater independence. At the moment, it’s the only way to ensure the Villa’s survival. But it’s obvious that any type of funding comes with a set of expectations and conditions, often in the form of unwritten laws. In both cases, the art functions as a ‘good will umbrella,’ a kind of advertisement. And whether they want to admit it or not, the artists are trapped in a process in which they culturally legitimize the funding agency, regardless of whether it’s the bank or the state. It would be far more consistent to exit this system altogether, but almost nobody does this. I can still remember the days when corporate sponsorship was completely new and artists didn’t want to be associated with a company logo—it was considered embarrassing—but this system has become so normalized by now that hardly anyone remembers it. ‘Dropping out’ is looked upon as unprofessional.

The function of art qua art is to reveal, shed light on, and address grievances and contradictions, including hypocrisy. Art is a critical instrument and not a PR tool. A country like Germany should have the stature to allow its artists to work with the devastating facts of its history, to expose the skeletons in its closet. In other words, you have to really want art and be able to take it.

AJS:

And at the same time there’s always the danger that the institution is merely adorning itself with its alleged openness to criticism. Ultimately, this strategy drained a lot of the power out of institutional critique. The criticism was absorbed, and in the process, it was neutralized. Suddenly, artists were being invited to criticize the institution. As Jonas Staal explained in his book Post-Propaganda,[5] this is how institutions try to demonstrate how open they are—even though not much has changed in structural terms. Marion von Osten once referred to this as “cosmetics” and asked: “Where does rage take place? Dissens? Wut?[6] [. . .] if the institution becomes so soft and takes everything?”[7] This is where she makes a plea for art’s “uselessness,” which I understand as a demand for poetry, as a strategy of withdrawal—not out of an entanglement, but out of being utilized as a ‘cosmetic.’ But then where do criticism and anger find their political place? Could it be precisely through membership in an association? In artists becoming active and exerting a concrete influence on the structures of the institutions?

I can barely remember the first general meeting I attended. It must have been three years ago; it took place in the Deutsche Bank building. I remember going there on my rickety bicycle and wondering if I should chain it up out front. The building looked like a maximum-security unit, with locked channels and controls, like an airport. You were led straight into the room where the general meeting was to take place, and were not allowed to wander around the building on your own. I don’t remember much of the meeting itself. We were supposed to vote people onto the executive board to replace the Deutsche Bank representatives. Everything seemed to have been worked out in advance, and Olaf Nicolai and Markus Müller were elected. There was very little discussion and not much friction concerning the items on the agenda, but even back then I sensed there was some surprise at our presence. After the general meeting, we, the artist members, sat together for the first time at a long table in a nearby café. I think almost everyone who was there remained a part of the core group of committed members. I wasn’t in Germany when the next general meeting took place. When was the first time you attended one?

AS:

Before I answer your questions, let me just add that when curators invite artists to take part in exhibitions on themes that might make sponsors uncomfortable, one can of course wonder whether they shouldn’t assume a part of the responsibility, whether they shouldn’t already, in the conception phase, be thinking about how to counter the ‘cosmetics’ effect with a different strategy. But independence is expensive; large-scale exhibitions are contingent on money, space, and infrastructure, and can hardly be pulled off without the requisite funding. This very clearly demonstrates the split situation we find ourselves in.

For some of us, in the aftermath of our recent experiences, your question as to where criticism finds its political place becomes even more personal. As members of the Villa Romana Association, we not only wanted to contribute our view of everyday life at the artists’ residency house, but also of the program itself. We wanted to clarify how a representative artists’ institution can and should act at this time, situated as it is in a dense web of cultural and political debate—where the responsibility lies and where there’s a need for clarification. It now seems that we were naïve to assume that our contribution was desired and needed. And yet we’re the experts—the ones with the education, years of practice, and professional exhibition experience. Many of us are professors and are currently educating the next generation of artists. The majority became members out of a sense of love for the place, of gratitude. I didn’t see anyone driven by defiance or anything similar—the anger came as a result of the experiences we had with the board.

I didn’t attend the first general meeting at Deutsche Bank. At the subsequent general meeting, in October 2020 at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, I was surprised by the body language of some of the board members. Angelika Stepken spoke at length about the many events that took place in the Villa Romana’s garden in spite of the pandemic and lockdown. It seemed to me at the time that the chairwoman of the board kept turning away and avoiding eye contact with Angelika Stepken, wasn’t following the projected images of the various seminars and workshops that took place in the framework of the “scuola populare.”[8] My impression was of a public display of distance and disinterest, and it struck me as disrespectful.

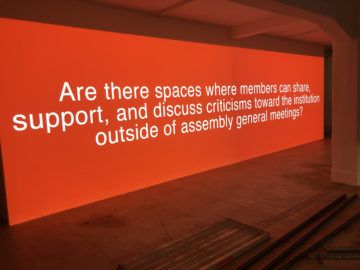

Among other things, the agenda included voting on an amendment to the statutes to enable the formation of a new curatorium (advisory board). We also elected a new member to the board of directors, Lanna Idriss. Later, in response to a question the artists posed asking to clarify the terms of candidacy—it was already the second general meeting at which members expressed the clear wish to elect one or more artist members to the board of directors—the chairwoman answered consolingly that the board was only there to implement ‘our’ wishes, that it didn’t decide anything on its own, but saw itself as a mere representative body, etc. One of the artist members stood up and presented herself ad hoc as a candidate, delivering a brief biography and explaining the reasons behind her desire to run for the board. Despite her friendly demeanor, the non-artist members were evidently outraged by this spontaneous act. In the end, we all decided she should run at a later date in order to comply with democratic procedure, because it was clear that all members should be informed in advance about potential candidacies and thus have the option of either voting or giving a power of attorney to a proxy. This was all fine and good; at least the subject had been brought up and voiced unequivocally. At some point I raised my hand and asked if the board could explain to us why Angelika Stepken’s contract had only been extended for another year “due to corona.” The chairwoman seemed to grow angry; she refused to discuss it any further. Apparently, she interpreted my question as an attack; in any case, the incident stuck in my mind as a textbook example of gaslighting: the simultaneous assertion that everything was being done solely in “our name,” while refusing to utter another word on the matter. It was an assertion of power and was pronounced as the final word. Later, when we discovered that none of this had been recorded in the meeting’s minutes, I wondered whether we should insist on its inclusion, because anything that isn’t recorded in the protocol didn’t happen, so to speak. It wasn’t the first time the board would virtually erase the reality of our experiences with them.

AJS:

As members, we not only have the right but, as I understand it, the duty to demand transparency. Because one of our tasks is to relieve the board at the end of each year.

I found the mail from December 5, 2019, in which the board of directors expresses their pleasure over the influx of artist members—they describe it as a “strong basis for leading [the association] into the future.” And in reference to members’ involvement, they cite the original profile of the Villa Romana as an artists’ house originally founded by artists.

This, of course, is something we’ve often argued ourselves. I see it as part of the strategic exercise of power you’ve already mentioned and which causes the act of speaking to degenerate into empty cliché. Because in the general meeting you’ve just talked about, there already seemed to be a strong resistance to the members’ questions. Later, I noticed how much the chairwoman appealed to the members’ “loyalty.” She employed this term several times—as if articulating criticism or posing questions would not only disrupt or delay the procedure, but already signalized a break in our common interests. This unspoken accusation precludes any possibility of dissent while ignoring the fact that the concept of membership is that it also serves as a control body for the board’s work, and that this not only creates transparency, but requires it. Sarah Ahmed describes the complaint as “diversity work.”[9] Diversification, in this context, is to be understood as working toward opening up institutions to let in social groups that have been largely excluded from them previously. This work is apparently not welcome here.

The escalation seems to have begun the moment the artists sought to leave their position as ‘spectators’ and actually join the board. In this respect, the last general meeting in the screening room at Martin Gropius Bau was, to my mind, symbolic: while the members were sitting in the auditorium, the board of directors was up on the stage, well lit, seated in front of a screen. We watched as they ‘took place.’ The voices from the back row were barely audible, while the view of the stage remained unobstructed.

If it were true, as the chairwoman claims, that the executive board merely represents and implements the wishes of the members, then why did the candidacy from the ranks of the artist members come up against so much resistance? Who were these other members that felt so offended by it?

AS:

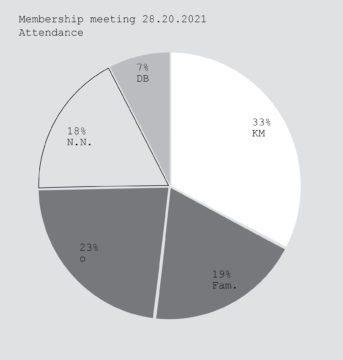

At the last general meeting, in October 2021, we were suddenly confronted with the fact that the board had, without our knowledge, recruited around 40 new members—presumably to ensure a majority in their favor. Who are these new members—are they from the chairwoman’s family, are they employees? It was fairly obvious that they had been clued in ahead of time, because the numbers you wrote down indicate that they pretty much all voted against our candidates. And that’s sad, because it indicates that the board doesn’t want to see that we’ve been completely forthright with them and have only acted in the interests of the Villa and of carrying on its tradition. But I’ll come back to that shortly.

I can well imagine that the chairwoman identifies closely with the Villa. She’s been on the board of directors since 1988 and has supported the institution financially for many years. It’s understandable that she wants to closely monitor the transition to a new form of financing. After all, she wants to secure the Villa’s future. But it’s hard not to get the feeling that she sees the Villa Romana as a form of private property.

In her position, she’s probably not all that accustomed to people disagreeing with her. And so it can seem that the proximity to her and her money has influenced her employees’ behavior. But we’re not employees, and this isn’t about loyalty or, let’s face it, obedience. We’re interested in communicating on equal footing, and unfortunately, she doesn’t seem to be up for that. Which makes things pretty difficult.

AJS:

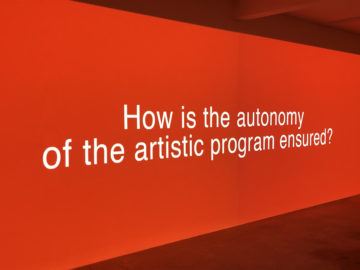

For the board of directors, an artist running for election must have meant danger: the potential infiltration of a circle otherwise accustomed to being among its own kind. Fundamentally, the association’s structure allows for a majority to form among organized members—regardless of the agenda they happen to represent. The statutes of the Villa Romana are vague in this respect, because there are no declared values. All that’s stipulated is the association’s function in the “promotion of art and culture.” Perhaps that’s why the dispute with the board is so complicated, because there is no ‘we’ that could gather around a shared vision of the future of the Villa Romana. While the artist members have tried to articulate what the Villa Romana means to them, the meaning of the Villa Romana to the board members remains entirely unclear. Just as unclear are the interests the BKM is pursuing, i.e., the purpose this German project in Italy is supposed to be serving in terms of German cultural policy today. And the relationship between the board and the BKM is anything but transparent.

The only concrete result of the negotiations between the board and the BKM can be found in the amendment to the constitution:[10] the establishment of a curatorium, in which two of five members are BKM representatives; the approval of the budget by the curatorium; payment of the director’s position in keeping with the public service payment tariff; and the right to veto that BKM representatives retain when appointing the new director. This means that the choice of director is largely in the hands of the BKM and, as such, is anchored in the statutes. It seems plausible that the refusal to extend Angelika Stepken’s contract is also related to the negotiations between the board and the BKM.

AS:

It seems plausible to me too. Why, though, couldn’t the board just communicate this clearly to the members? Because the result is that Angelika Stepken’s tenure ends in a way that’s unworthy. Whereas she should have been thanked for her visionary work and asked how much time she still needed to bring to conclusion projects that have significantly shaped the Villa’s identity and transformed it into an internationally renowned platform for critical thinking. Or they could have coordinated with her how to ensure the smooth continuation of the various structures and networks she’s built up. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. This is why we’ve been campaigning for the continuation of these structures and networks, through becoming involved in appointing the new director.

I’m going on the assumption that the board members—all board members—only want the best for the Villa Romana. But if one wants to raise the question of ‘undeclared interests,’ perhaps one also needs to talk about the proximity to this tremendous amount of money and the relationships and dependencies that might lead to within the board.

AJS:

A lack of gratitude, albeit toward the funding sources, is something they accused Angelika Stepken of. And that the artist members are only acting on her behalf.

I was also confused by the way the nominating committee was put together. Because a nominating committee to select the short list for the director’s position, consisting of five members—three from the executive board, a representative of the BKM, and an artist—, is certainly not independent of the prevailing power structures within the association, even if they claimed it was “common practice.” In the end, the board—i.e., the same people who already make up the nominating committee—has the final say in selecting one of the nominees proposed by the committee. And through the change in the constitution, the BKM has a veto option in the board of directors’ final decision. Basically, you could say that the board and the State Ministry for Culture decide, while an artist recruited from among the association’s members is allowed to take part in an advisory capacity, but doesn’t have a vote. This is pretty much the sense I have about the entire association structure at the Villa Romana.

When I questioned the nominating committee’s independence from or dependence on the board of directors during the last general meeting, the board answered by claiming that it was impossible to change the statutes, which determines this particular constellation. Which isn’t true, because the nominating committee isn’t even mentioned in the constitution—it was only set up as a result of lengthy negotiations between the artist members and the board. According to the association’s constitution, the board reserves the right to select the new director. In the minutes of the general meeting, my comment was misleadingly recorded as “a wish for more artists in the nominating committee.”

Did the artist members already have contact with each other in the run-up to this general meeting, or did the intense level of exchange come about afterwards? How did it begin?

AS:

I would have liked to submit a formal objection to every protocol thus far, because our point of view, our clearly articulated motives have always been either falsified or omitted altogether. But you have to choose your battles.

In answer to your question: We had no contact with one other prior to the 2020 general meeting, and there was no coordination at first. I was pretty shocked after that meeting and felt the need to communicate the effect it had on me. I asked Angelika Stepken for the list of all artist members and sent out an email. I should perhaps mention that Ms. Stepken was not among the recipients of these mails. In the beginning, when we were still hoping to get her contract extended, we thought that it might be somewhat awkward for her to be involved in the discussion. A short time later, I wrote a letter to the board asking for a more productive form of cooperation and more transparency concerning the admission of new members, among other things. The letter included input from several other artist members of the association. It also addressed the Villa’s representative character and its uniqueness as a cultural hub for the entire Mediterranean region. The letter was signed by 41 members, around half the total membership body of the association at the time. In my opinion, this gave us a clear mandate. The reply that arrived a few weeks later made no reference to any of the points raised in the letter. Instead, it contained the following sentence: “If the relationship with our sponsors becomes strained and the foundation for a trusting cooperation called into question, the consequences would mean an endangerment to the 115-year existence of our private association.” In other words, our letter was interpreted as a threat to the future of the Villa.

In the end, after several months of friendly insistence, we were finally able to persuade the board to talk to us. I think they realized at some point that they weren’t going to get rid of us any time soon. We were careful to follow the rules they set up: we weren’t allowed to take notes on our private Zoom meetings with them during the first half of 2021, for instance, or share anything from these meetings with the other artist members. It was tough going: sometimes the board members were hostile towards us, at least that’s how it seemed to me, but over time a few points began to crystallize. They hired someone to take care of communications and to ‘welcome’ new members, which was one small improvement. And they agreed to a newsletter (which was only sent out once, however, with the last invitation to the general meeting). We thought that we’d finally won them over with our trustworthiness and sincerity, and the situation seemed to be getting easier. One of our candidates met with the chairwoman privately, and everything looked like it was moving along smoothly. And then came the big disillusionment at the last general meeting, when we were presented with an estimated 40 new members and their dissenting votes. All at once, it seemed that they’d lied to us and had merely pretended to be interested in communication and cooperation. After the meeting, as two members reported, the chairwoman admitted that she’d always intended to vote down our candidates. What amazes me is that she and the other board members are not in the least bit ashamed of it.

If you take a look at these structures, it’s interesting to see who’s keen on getting a position on a board like this—what do they hope to gain from it? What do they know about the reality of artists’ lives, or their artistic production? It’s clear that they see some benefit in it; the companies they represent or are associated with know how to use this cultural capital. I’ve been faced with the realization that as an artist and intellectual my presence is neither welcome nor desired, even though I am one of the people actively producing culture today. This question also becomes a class question, even if this is not generally stated openly.

AJS:

When I was introduced to the chairwoman as the person who would be delivering one of the artist candidate’s statements, her spontaneous reaction was to tell me that I’d been lucky to have gotten in at all, because the control at the door was very strict. Evidently, it was beyond her that someone who looks like me could be a member of this association. If this lack of imagination is one of the prevailing features here, what does that imply in terms of speaking or being heard in these spaces?

Actually, very different ideas exist regarding a board of directors’ duties. Online you can still find video footage of a talk show that took place in 2003 at the Kunstverein Munich[11] which discusses Andrea Fraser’s work Eine Gesellschaft des Geschmacks (A Society of Taste, 1993). Among other things, the participants talk about the job of the board of directors in terms of raising money, but also in their capacity as “bodyguards” for the artistic director. They refer to the board of directors as the bodyguards of the overall association. A question arises here: against whom is the board protecting the association?

AS:

Unfortunately, I don’t know Fraser’s work on the Kunstverein Munich—the fragmented elements from the 27 hours of interviews she conducted with the board members of the Kunstverein Munich and then reassembled in the form of a dialogue. But her various commentaries on power relations and self-prostitution in the art world are well known. In the talk show, which didn’t take place until ten years later, Bazon Brock called her work “weak” and referred to her as “massively naïve.”[12] He accused her of being an American with no notion of recent German art history (because criticism of the kind was nothing new) and said she was like a “neutral litmus strip due to her lack of education and knowledge.” It’s always interesting to see this age-old strategy at work: discrediting the opponent in order not to have to face up to the criticism. Incidentally, we’re talking about a female opponent and a fundamentally patriarchal strategy here—but that’s just a side note, because what’s even more interesting is that an artist who takes this questioning of institutional structures and makes it the core of her work is seen as an outright opponent, an outsider.

As the former director of the Kunstverein Munich Helmut Draxler remarked: “The crucial question is: what do people want?” What motivates art critics, art functionaries, and art mediators to become members of such an association? How do they see their role, apart from raising funds? Brock describes the ideal board as an “enclosure,” as a space of protection from a public uninformed about art.

AJS:

In the case of the Villa Romana, it seems as if the board of directors were protecting the association from its own members and artistic director. Because by recruiting the new members, the board has created a majority that cements their position—after having pronounced a ban on all further admissions. In doing so, they don’t seem to be doing justice to the democratic principles the organization, in the form of the association, calls for.

What, then, remains of the association apart from the executive board—the money and the representative character in the sense of a brand? If you were to take the artistic program seriously and transpose it onto the structure, you’d have to ensure that the financing and the interests and people connected to it have no influence on the association. Precisely because this program has an anti-racist and decolonial focus. ‘Decolonial’ means a critique of ruling structures. You cannot criticize the structures without questioning your own position and actively working on structural change.

If the board were really interested in its new members, as they claimed in the mail cited above, all Villa Romana prizewinners should automatically become members. Moreover, in order to make the association more accessible to all, the membership fee would have to be reduced. And they could also invite the more than 200 cultural workers from Florence and Italy who are committed to the Villa Romana and who wrote an open letter about the role the Villa Romana plays in the Italian cultural landscape.[13] Instead, the board neglected to respond to the open letter in any form at all.

AS:

It’s always interesting to look at how the whole thing started with corporate sponsorship. Back in 1982, Hans Haacke analyzed the phenomenon—still very new at the time—in his exhibition “Mobil Observations,” which was shown at three Canadian locations and took a close look at Mobil Oil. In Musings of a Shareholder, he satirizes Mobil Oil:

“Although our tax-deductible contributions are hardly equal to 0.1 percent of our profits, they have brought us extensive good will in the world of culture. More important, however, opinion leaders and politicians now listen to us when we speak out on taxes, government regulations, and crippling environmentalism. The secret for getting so much mileage out of a minimal investment is twofold: a developed sense for high-visibility projects at low cost and well-funded campaigns to promote them. [. . .] Museums now hesitate to exhibit works which conflict with our views [. . .].”* [14]

Although it’s not all that long ago that these structures were still completely new, the statements of PR campaign architects—such as this one referring to doing business in foreign countries: “the arts are an important means of ameliorating the conflict between political nationalism and international business”[15]—seem almost touching from today’s point of view. These campaigns opened up unprecedented opportunities to directly influence policies not only at home but also in foreign countries where Mobil Oil’s promotion of business interests, including colonialist and deeply racist interests, went largely unnoticed. This new subsidization of art on the part of large corporations represented a change in paradigm, the effects of which reached far into the economy and politics and transformed the art world to the degree that we can no longer imagine it any differently, i.e., without this major funding. We should think about what that means.

Haacke’s 1971 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum was canceled at short notice due to one of the works he’d planned on including, an investigative piece on New York’s slumlords. His first solo exhibition in an American museum, at the New Museum, didn’t take place until 1987. Haacke’s work was difficult to digest at the time; there was no such thing as politically motivated conceptual art, and his interest in unmasking the funding structures of cultural institutions was seen as airing the art world’s dirty laundry. Hans Haacke’s work addressed something that had been largely obscure up to that point: in 1980, Mobil Oil had sponsored a major exhibition of Nigerian art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in order to distract from its financial interests in Africa, from systemic poverty, apartheid, and colonial exploitation, and to “blunt attacks from Black Americans.”[16]It turns out that the company had, despite a UN embargo, been supplying oil to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, as well as to South Africa’s police and military. Haacke was interested in establishing transparency. If the great corporations were on their way toward becoming indispensable for museums and art institutions, it was going to become impossible at some point to criticize these institutions. But corporate sponsors can gain this immunity to criticism far more cheaply, by sitting on boards, for instance, and donating smaller, tax-deductible sums.

AJS:

For many of them, I think it’s important to cultivate the appearance of criticism, at least on the surface. In Jonas Staal’s Post-Propaganda, I came across the following passage:

“Art is expected to be open and tolerant, to do its best to resist dogmatism and ideological deployment, to avoid the mistakes of the past—to avoid the ‘lumping together’ of certain communities and minorities.”

He continues:

“Is it not the case that the visual arts are the desired embodied image of democratic ideology—democratism—when it is self-critical, questioning, tolerant, continuously developing, and displays a deep interest in others? [. . .] Is it not the case that this is the actual task that the state has given to artists by means of all kinds of foundations, tax cuts and art schools: to show the rest of the world the success of this free society and its citizens?”

Staal contrasts this with the armed invasion of Iraq and the decades-long deployment in Afghanistan—all the violent undertakings in the name of ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom.’ His analysis, formulated in the context of the Netherlands and the year 2010, can certainly be transposed onto German cultural policy today.

But it’s precisely this “self-critical, questioning, tolerant” illusion that art perpetuates when it enables institutions and nations to hide their white power structures behind an exhibition program that is as ‘diverse’ as possible. To my mind, this is one explanation for how the chairwoman can stress how much she appreciates the focus of Angelika Stepken’s program of the past several years and continue to support the Villa Romana financially, yet can turn her back in the way you’ve described, or even, as we witnessed at the last meeting, close her eyes.

What is the relationship between the many BIPOC[17] artists and the themes that have dominated the Villa’s program in recent years, the board, the curatorium, and the majority of the association’s members? Or what is the relationship between the humanitarian crisis in the Mediterranean and the romanticized notion of German artists working free of care in Florence?

Monika Grütters (former German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media) responded in outrage to a statement and demand made by the SPD (Germany’s Social Democratic Party) titled “Schulterschluss von Geist und Macht” (“Closing Ranks between Intellectuals and Power”: the reference here is to culture and politics)[18] with her article “Eines darf die Kunst nicht sein: Eine Tochter der Politik” (“One Thing Art Must Never Be: A Daughter of Politics”),[19] because “art is a daughter of freedom.” One gets the impression that she hasn’t actually read the article she’s responding to, that she’s merely reacting to its title. Because a lot of what she offers in the way of counterargument can also be found in Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s position. Both sides express their appreciation of cultural diversity and art’s ability to “bring different sides together” and act as common ground. Both reject art in the form of “bourgeois ornament” and “gourmet delicacy” and seek to establish culture as a national goal. “Active cultural policy is active democratic policy” and “keeps democracy alive;” it’s “systemically relevant” and “promotes democracy.” Grütters writes: “Art is free when it neither has to bow to market logic nor is forced to serve a political agenda, a world view, or an ideology.” Grütter’s demand that “no artificial barriers be erected between private and public funding” probably has a kind of public-private partnership (PPP) in mind. In the case of the Villa Romana, we have an institution financed by tax revenue, while the money is entrusted to individuals from the private sector acting as statutory legal representatives.

Olaf Scholz addresses another ‘PPP,’ namely the goal that “our society’s diversity be represented equally among the programs, producers, and public.” If we speak of “representation,” however, this should include both aspects of the word’s meaning: representation, i.e., showing/making visible the diversity existing in society, as well as establishing representation in the structures, not merely as part of the public or through the programs and producers, but also through active participation.

I wonder if it might be better to start by taking a closer look at the already powerful connection between politics and art. A recent exhibition on the history of the documenta at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin provided an impressive demonstration of this connection.[20] Documenta, financed mainly by the Federal Ministry for Intra-German Relations, was conceived as a flagship Cold War project intended to demonstrate to the Eastern Bloc how forward-looking and open the new democracy was. It was all about fighting communism, and that agenda was a key factor in who and what was exhibited.

The research on Werner Haftmann—one of documenta’s founders who had previously worked at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence—shows the degree to which the ranks of decision-makers at the first documenta of 1955 were still tainted by National Socialism (10 of the 21 people were former members of the NSDAP; Haftmann himself was an active National Socialist and took part in the shooting of Italian partisans). The exhibition on the history of the documenta also demonstrates that the Villa Romana was an important reference point early on in the history of German art and artists’ institutions.

In truth, an art association like the Villa Romana is predestined not only to question its own structures but also to transform them, because, unlike other institutions, this potential lies in the members’ hands. All throughout our various discussions, I heard some of the artists voice the fear that if we publicly criticized the members of the board, it could spell the end of the association. I’m convinced that misinformation and an implicit fomenting of fear are part of the strategic and rhetorical repertoire of individuals disinclined to change prevailing structures. However, the federal government now supplies the bulk of the Villa’s funding and public sponsorship justifies public interest. Moreover: according to its constitution, the Villa Romana does not represent the private interests of board members, but serves the public good.

AS:

Yes, it’s unfortunate, but a fear of the power this tremendous money wields played a big role in all this, and I’m pretty sure this fear was deliberately instilled. Shortly before the last general meeting, a rumor popped up that a number of other board members would resign if the chairwoman, who was up for re-election, was voted out of office. But we’d never seriously considered this, and their paranoia was quite possibly feigned, given that the board had already created new majority conditions by taking on around 40 new members. In any case, the artists understood this as a clear threat, and our candidates were unnerved. The message was this: if the executive board steps down, there will be a scandal, as a result of which the federal government will lose confidence in the association and the financing of the Villa will become jeopardized. Because artists mean chaos. It was a bluff right out of corporate culture, of course, and it happened at the very same time that they were privately promising to support our candidates. At the general meeting, the board in fact formally proposed our candidates. Was it all just carrot-and-stick? In our various Zoom meetings over the past year, I started to sense a good cop/bad cop strategy at work: it was obvious that they were rotating the roles. If one of them happened to be relatively open and friendly toward us, the next time they’d act the part of the aggressive opponent, and vice versa. After the last general meeting, I was ready to go to the press. Everyone was outraged. To me, this seemed like the only way to force the board to finally talk to us in any meaningful way. Unfortunately, there was no majority for this decision, because people still feared damaging the Villa in some way and hoped that the participation of one of our artist members in the nominating committee would exert influence on the selection of the future director.

In a corporate culture of this kind, artists can only play the naïve, gullible idiots. It’s about exercising power, and not about the right to participate in a discussion. It’s about capitalist logic, about winning, about a climate of firing people without notice. But this is an artists’ institution founded by artists, and now it’s financed almost entirely with public money, and as such it requires transparency. It’s an artists’ house where a very different critical climate prevails.

AJS:

We now have the minutes and the list of members who attended the last meeting. At the time, when you asked who these other members were and whether they were employees of the chairwoman’s family, I thought it was a provocative allegation—maybe even completely inappropriate. But if you take a closer look at the list, it turns out you weren’t wrong at all. Fifteen people are from her immediate family (sister, niece, brother-in-law, etc.). Together with employees, long-time friends, and business partners, they made up more than 40% of all votes cast at the last meeting. And those are just the ones that can be researched relatively quickly. Incidentally, at least one of the newly occupied positions on the curatorium can also be allocated to the chairwoman’s circle. On the other hand, the representatives of the BKM were in attendance as non-voting guests, but of course they’ve entrenched themselves in the statutes.

With all the e-mails going back and forth between the artist members after that meeting, it got to the point that I no longer understood what was going on. I wrote a less than friendly e-mail to everyone in which I expressed my frustration.

AS:

Yes, and it was this e-mail of yours that brought us together.

AJS:

Demanding participation in the committees is about having a say. Looking at the situation now, I wonder what we would have achieved with this participation? Because behind that demand, perhaps, is a desire, as artists with a certain expertise and perspective, for artistic and political relevance. But even a position on the board would not have guaranteed that. Because what we’re demanding politically for the Villa Romana runs counter to the interests of politics and the private sector. The Villa shouldn’t be a representative institution characterized by its proximity to the art market and collectors, but a place that brings together artistically and socially relevant positions from Germany, Italy, the Middle East, and the African continent. And these are positions that might well call Germany’s democratic image of itself into question. A place that offers opportunities for unconventional action and a space for experimentation. But even the opinions of the artist members diverge. How would you describe these different interests of the members, politics, and big business?

AS:

That’s a tricky question. In the end, after the debacle of the last general meeting, I wasn’t 100% clear what the point was when the decision was made to become part of the nominating committee. At the time, it felt like a farce to me.

But even before that: the artist members had agreed to so many compromises that in the end, it seemed to me that the existing structures would absorb and ultimately silence our candidates, even if we did manage to get them elected. This is not a reproach, incidentally, and I’m grateful to them for their willingness and courage. But when I told some of this story to a friend with political experience in various (non-artistic) fields, she said: “Forget it. You can’t compete with these people, and you’ll never be able to navigate these structures. Their interests and spheres of influence are too broad, too invisible: you won’t understand when things reach a tipping point, let alone be able to interpret the situation correctly, even if it’s happening right under your nose.” That was very sobering.

What, indeed, did we want? A say in things, a degree of influence. We wanted to elect someone to the board who, when necessary, would remind them what the Villa stands for; someone on the curatorium who would keep an eye on these processes and ask questions. We saw the candidacies as a first step in a longer-term process of gradual, respectful change. Since this already seemed like too much of a threat to the board, you have to wonder about the underlying reasons. What did they see us as? I find it difficult to understand that some of the artist members took the allegation that our candidates were “not electable” seriously, as a criticism of their performance, their statements, and their skills—because that’s how you adopt the board’s logic. What does “not electable” even mean? Electable for whom?

In the weeks leading up to the last general meeting, when the possibility that one or both of our candidates might be elected still seemed realistic, it occurred to me that it might make sense to talk beforehand about how to prepare ourselves for any changes in dynamic that might arise between us. Because it was clear to me that a given problem might suddenly look completely different from the perspective of the board or curatorium: that one could find oneself in the unpleasant situation of suddenly being on the ‘other’ side and having to realize that the artists ‘don’t understand’ and that you have to weigh your words more carefully, that you’re no longer allowed to speak openly. I raised the question, but no one responded. The candidates had their own concerns: what were they getting themselves into, and would they still be able to rely on our support afterwards? It was a squeamish moment, and we could only express our unconditional trust and say yes and hope for the best.

But back to the subject of art and politics. I grew up with the large-scale paintings of the Abstract Expressionists in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and it was a kind of turning point for me to discover the research of the British historian Frances Stonor Saunders in her 2001 book The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters.[21] Today, it’s widely known that the CIA ran an enormous campaign during the Cold War to champion abstraction as the universal emblem of the free world and to covertly fund it on multiple levels. In 2018, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt presented the exhibition “Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War,” which was based on Saunders’s research but neglected to mention her in more than the most cursory way. Be that as it may, I see numerous parallels to the documenta exhibition at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. What can we learn from this? That there’s probably no such thing as major art funding without a political agenda.

In an interview, the curator of the exhibition at the DHM, Julia Voss,[22] describes how the artist Emy Roeder, who was a fellow at the Villa Romana during the Nazi years, kept referring in her letters, well beyond 1945, to her painter friend Rudolf Levy, who was deported and murdered by the Nazis—while Werner Haftmann crossed out Levy’s name from the list of potential participants in the first documenta exhibition of 1955. Visitors were able to view the original, written in pencil on paper, with their own eyes: a list of artists’ names, with Levy’s name crossed out. Until his arrest and deportation to Auschwitz in 1943, Levy had a studio in the Palazzo Guadagni, in the same building as the Deutsches Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, where Haftmann worked as an assistant for many years. To my mind, it’s unlikely that the two never met; he obviously knew the painter’s work. Haftmann held onto his apartment in Florence throughout the war. It’s been documented that he visited his former employer several times during that period. Decades later, in 1986, Haftmann attempted to gloss over the absence of all the murdered Jewish artists at documenta 1. In his extensive illustrated volume Verfemte Kunst. Bildende Künstler der inneren und äußeren Emigration in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (Eng.: Ostracized Art. Artists in inner and outer emigration in the National Socialist era), he suddenly dedicates a double-page spread to Levy, an artist “nearly, and unjustly forgotten today.” Not a word about the fact that he himself, as director of Germany’s most important post-war exhibition, was directly responsible for this act of forgetting. But his important position in the art world led the people who knew to keep quiet. The consequences were clear to everyone involved.

The American author Rebecca Solnit speaks of a continuum of misogyny, with the catcall at one end of the spectrum and violent sexual crime at the other, and in between the whole range of micro- and macro-aggressions that women are constantly subjected to.[23] And let’s not forget the accusation that it was all in their imagination. I see a similar continuum between artists and the major financial interests of the art world: intimidation at one end, blacklisting in the form of exhibition cancellations and the withdrawal of funding and awards at the other, with more direct methods of sabotage and character assassination in the extreme cases. This is the structure of power abuse. How does one react? With defiance, resignation—or with a kind of anticipatory self-censorship?

Some of these people are in a position to undermine our work and credibility on juries, committees, and boards of directors, and to sabotage career opportunities; this is a statement of fact, it’s not as paranoid as it sounds. The invisible power of this enormous financial differential is its own form of violence. To come back briefly to Haacke: one might find him outdated, but the more I study his works from the 1970s, the more relevant they feel to me. One has to bear in mind that artistic positions that have fundamentally changed the way we see art often seem oddly outdated: it’s hard to peel away the changes in perception they brought about. In retrospect, it becomes almost impossible to recognize the utter newness of the work, its groundbreaking aspect. But what Benjamin Buchloh wrote in 1988 still applies today:

“What the reception of Haacke’s work does prove is that the supposedly all-embracing liberalism of high-cultural institutions and of the market may be far more selective than is generally believed, and that those institutions can be rather rigorous in their secret acts of revenge and clandestine repression. It seems that Haacke has too often challenged institutional power and control, and that the institutional, discursive and economic apparatuses of international high art have not forgiven him for ‘baring those devices.’”[24]

But back to the Deutsches Kunsthistorisches Institut, Rudolf Levy, and Werner Haftmann: at the end of the above-mentioned interview, curator Voss sums it up thus: “Anyone interested in the untold stories of the post-war period is best advised to stick to the outsiders.” She’s referring to the artist Emy Roeder, but maybe there’s a larger truth in this.

AJS:

And yet our discussion over all that’s happened, in the form of this conversation and its publication in an art context, is an opportunity to put it all up for renegotiation, to introduce it to the public discourse. The current boycott of the “Kunsthalle Berlin” and the artists who have withdrawn their works from the “Diversity United” exhibition demonstrate that a framework exists in which artists can act and take a stance.[25] And this doesn’t have to be against professionalization, but precisely because of it. Audre Lorde’s quote “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” keeps coming to mind.[26] The commitment of the artist members over the last few years—who did not, in fact, aim to destroy the association, the board of directors, or the Villa Romana, but merely asked that their perspectives be recognized—was disregarded and disparaged.

Due to the newly created majority conditions, all the ‘tools’ legally available to the association’s members (i.e. to submit motions, call for transparency, vote) have been rendered useless. It’s not about the ‘sensitivities’ of individuals here, but about addressing structural shortcomings that aren’t limited to the Villa Romana alone.

Anike Joyce Sadiq and Andrea Scrima will discuss “Against the Erasure of Dissent” at the Villa Romana on June 10, 2022 as part of the three-month conference “Manifestiamo.”

6:30 p.m., via Senese 68, Florence, Italy

Additional panel participants: Simone Frangi, Justin Randolph Thompson, Lucrezia Cipitelli, and Alessandra Ferrini.

“Against the Erasure of Dissent” is a collaborative text and an artistic work printed in an edition of 500 as part of the exhibition “Mit Glück hat es nichts zu tun” (It has nothing to do with luck) by Anike Joyce Sadiq, presented at the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart (2022) in Germany. The exhibition can be seen through September 25, 2022.

For more on the history of the Villa Romana, click here and here.

* Relevant in this context is how Arend Oetker describes the creation of the Galerie für zeitgenössische Kunst in Leipzig (GfzK), in which he played a significant role: “ [. . .] One also had to employ a bit of cunning, because of course I used the cooperation with the city and the state. I sat and continue to sit on the supervisory board of the Neue Messe. They probably didn’t dare to entirely ignore or categorically reject this request [. . .].” From the conversation between Neo Rauch, Georg Girardet, Arend Oetker, and Barbara Steiner in the GfZK on August 26, 2008.

** Figures based on publicly available sources.

Footnotes:

[1] Federal Government Office for Press and Information, “Minister of the State Claudia Roth—The Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media,” https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/bundesregierung/bundeskanzleramt/staatsministerin-fuer-kultur-und-medien/staatsministerin-und-ihr-amt (accessed June 5, 2022).

[2] “Goethe-Institut und Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen regeln Zusammenarbeit neu,” press release, Foreign Office, Feb. 14, 2006.

[3] Anti-Humboldt-Box, Artefakte//anti-humboldt (Brigitta Kuster, Regina Sarreiter, Dierk Schmidt), AFROTAK TV cyberNomads (Michael Küppers-Adebisi), Andreas Siekmann, and Ute Klissenbauer, 2013

[4] “Unmapping the Renaissance,” symposium initiated and organized by Mariechen Danz (artist), Angelika Stepken (Villa Romana, Florence), and Eva-Maria Troelenberg (Max Planck Research Group at the Kunsthistorisches Institut Florenz), Villa Romana, Florence, 2015.

[5] Jonas Staal, Post-propaganda, Jap Sam Books and The Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design, and Architecture, Amsterdam, 2010.

[6] German for dissent, anger.

[7] Marion von Osten, “The End of Contemporary Art (as we knew it),” lecture in the framework of the exhibition “Politik des Teilens / Über kollektives Wissen” (Politics of Sharing / On Collective Knowledge), ifa Galerie Berlin, June 1, 2016.

[8] “scuola populare,” meetings, discussions, and workshops organized by Angelika Stepken, Agnes Stillger, Davood Madadpoor, and Radio Papesse, Villa Romana, Florence, 2020.

[9] Sarah Ahmed, Complaint!, Durham, 2021.

[10] The constitution of the Villa Romana is based on the German law defining non-commercial associations; there is no legal equivalent in US law, as these bodies are distinguished from other non-profit institutions, hence the terms used here—“constitution” and “statutes”—are to be understood as approximations of the German word “Satzung.”

[11] Talk show with Bazon Brock, Gabi Czöppan, Helmut Draxler, Ingrid Rein, as part of “Telling Histories,” archive and three case studies with contributions by Mabe Bethonico and Liam Gillick, Kunstverein Munich, 2003.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Open letter in support of the current director of Villa Romana, Angelika Stepken—To the attention of the directors of the Villa Romana Association,” letter by cultural workers from Florence and Italy, 200 signatories, September 30, 2021.

[14] Hans Haacke, from Upstairs at Mobil: Musings of a Shareholder, “Mobil Observations,” 1982.

[15] Hans Haacke, from The Goodwill Umbrella, “Mobil Observations,” 1982. Quoted from C. Douglas Dillon, “Cross-Cultural Communication Through the Arts,” Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. VI, No. 5, New York, Sept.–Oct., 1971.

[16] Hans Haacke, from Upstairs at Mobil: Musings of a Shareholder, “Mobil Observations,” 1982

[17] BIPOC is the abbreviation for Black, indigenous, and people of color. All these terms are political self-designations according to the glossary of the Migrationsrat Berlin e.V., https://www.migrationsrat.de/glossar/ (accessed: March 22, 2022).

[18] Olaf Scholz, Carsten Brosda, “Für den Schulterschluss von Geist und Macht,” Die Zeit, No. 37/2021.

[19] Monika Grütters, Joe Chialo, “Eines darf die Kunst nicht sein: Eine Tochter der Politik,” Die Zeit, No. 38/2021.

[20] “documenta. Politik und Kunst,” Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, 2021/22.

[21] Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, New York, 1999.

[22] Julia Voss, “Emy Roeder and the documenta,” DHM-Blog, 10/13/2021, http://www.dhm.de/blog/2021/10/13/emy-roeder-and-the-documenta/ (accessed: 3/22/22).

[23] Rebecca Solnit, Recollections of My Nonexistence, New York, 2020.

[24] Benjamin Buchloh, “Hans Haacke: Memory and Instrumental Reason,” Art in America, Feb. 1988.

[25] The “Kunsthalle Berlin” and the “Diversity United” exhibition are public-private partnerships centered around the cultural manager and chairman of the Stiftung für Kunst und Kultur e.V., Walter Smerling. Criticism and protest against both projects arose due to the blatant conflict between private, corporate, and political interests and the considerable financial support from public coffers. For more information on the protest see: Jörg Heiser, Hito Steyerl, Clemens von Wedemeyer, “Open letter: who owns the public?,” February 2022, https://transversal.at/blog/open-letter-who-owns-the-public and Candice Breitz, “Why boycott the ‘Kunsthalle Berlin?,’” February 2022, https://bpigs.com/diaries/guest-blog/an-open-letter-by-candice-breitz-why-boycott-the-kunsthalle-berlin (both accessed: March 22, 2022).

[26] Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, Berkeley, 1984/2007.

We do not claim that the given facts and events are complete. Nor do we assume any liability for the figures given, which may differ slightly from the actual figures.

“Against the Erasure of Dissent” is dedicated to all the artist members of the Villa Romana association who have devoted their time and energy these past several years.

It was not in vain.

©2022

Anike Joyce Sadiq and

Andrea Scrima