by Mark Harvey

I’m not a schoolteacher so I don’t know the exact routine that teachers have every morning before they leave their house, but I’m certain it shouldn’t involve checking the magazine of a 9mm Glock and perhaps even chambering a round before their commute to school. I have known several teachers and in general, they are idealistic, hard-working, and underpaid. The challenges of teaching 30 hyper 10-year-olds how to write a clear sentence or conquer fractions has to be consuming enough without also having a counter-assault plan in the back of your mind.

I’m not a schoolteacher so I don’t know the exact routine that teachers have every morning before they leave their house, but I’m certain it shouldn’t involve checking the magazine of a 9mm Glock and perhaps even chambering a round before their commute to school. I have known several teachers and in general, they are idealistic, hard-working, and underpaid. The challenges of teaching 30 hyper 10-year-olds how to write a clear sentence or conquer fractions has to be consuming enough without also having a counter-assault plan in the back of your mind.

The ideal of school as a safe, wholesome place for learning has been part of American culture since the Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock. Obviously that ideal isn’t always achieved and failures in our educational systems abound. But the notion of arming teachers—a notion that always comes up after mass killings in schools—suggests a societal failure at nearly every level. Teachers should be armed with things like chalk, markers, and pencil sharpeners, not 9mm pistols. And there was a time when our society was safe enough for schools to be open, breezy places, not “soft targets” that needed to be “hardened.”

What has to have been the worst day of their lives for the surviving children, teachers, and parents of Cobb School in Uvalde, Texas, is, I’m sorry to say, so routine in American life that one can predict the ensuing national dialogue, almost word for word, without any effort. It’s predictable, repetitive, and only punctuates the short spans between mass shootings. And it isn’t doing any good.

It goes like this: “Our thoughts and prayers go out to the families who have lost loved ones in this senseless massacre. It is beyond comprehension how this could ever happen. There will be time to discuss solutions to this sort of violence, but that time isn’t now. The time now is to grieve with the families who are hurting.”

And then there are various pundits on television talking about the issue, angry diatribes, a few failed bills in Congress, and in short time—wait for it—another Sandy Hook, Las Vegas, Parkland, or Uvalde.

Before I go further, I should qualify—or disqualify—myself on this issue. I own guns and enjoy shooting clay targets and paper targets at the range. I’ve hunted elk a good part of my life for the meat. Whether it’s because I live in a relatively safe community or because I don’t have fantasies about effectively doing a quick draw to kill a bad guy, I don’t own guns for self-defense.

There are 27 amendments to the Constitution, but the one most clung to by fanatics is the Second Amendment, the right to bear arms. In fact, plenty of people who can recite the Second Amendment word-for-word, will happily toss aside certain rights guaranteed in the First Amendment, such as freedom of speech, the right to peaceably assemble, and an implied separation of church and state under the establishment clause.

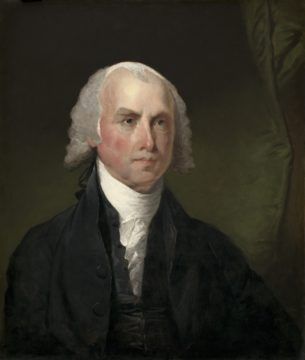

The Second Amendment has been parsed and parsed again. It was written by James Madison and is maddeningly vague enough that either side of the gun issue can stamp their interpretation on the 27 words contained in the amendment. And interpreting the amendment can get pedantically grammatical in a hurry. In fact, how the nine justices at the Supreme Court read the grammar has a huge impact on how easy it is to obtain a firearm.

The Second Amendment in its entirety reads, “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” This type of sentence has two parts: The first clause—A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of the state— is called a nominative absolute. The second clause—the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed—is an independent clause, and in law sometimes called the operative clause.

The interpretation of the Second Amendment depends a lot on how you see the relationship between those two clauses. The most popular grammarian at the time the constitution was written was Lindley Murray who in 1795 wrote the bestselling book on grammar simply called English Grammar. Murray definitely thought that nominative absolutes were logically tied to the independent clauses that followed them. One of his examples is, “His father dying, he succeeded to the estate.” The two clauses are neatly tied together and the nominative absolute at the beginning—the unfortunate death of his father—explains why the lad succeeded to the estate.

In 1934, two men were arrested for transporting an unregistered double-barreled shotgun with a barrel of less than 18” from Oklahoma to Arkansas. They were charged with violating the National Firearms Act which required certain weapons such as fully automated arms or short-barreled shotguns to be registered with the federal government. The men challenged the issue saying the National Firearms Act was unconstitutional as it usurped states’ rights and violated the Second Amendment. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court in 1939 in United States v. Miller (Miller was one of the defendants). But the Supreme Court decided against Miller and his accomplice. In the decision, the court repeatedly referred to the first clause about a well-regulated militia in the second amendment. An excerpt reads,

In the absence of any evidence tending to show that possession or use of a “shotgun having a barrel of less than eighteen inches in length” at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument. Certainly it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment, or that its use could contribute to the common defense.

For decades, the Miller case informed state and federal judges considering second amendment cases. The standard of “some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia” informed numerous cases when it came to the regulation of firearms.

But everything changed in 2008 in a Supreme Course case called District of Columbia v. Heller. The central question of the case was whether the District of Columbia could effectively ban the public from possessing handguns in Washington DC. Just as in the Miller case nearly 70 years earlier, lawyers representing the District of Columbia and the statute prohibiting handgun possession argued that because of the introductory clause, the Second Amendment was clearly written to ensure a well regulated militia, not an individual’s absolute right to bear arms.

The lawyers representing Heller argued that the amendment gave individuals the absolute right to possess firearms regardless of the clause about a well regulated militia. The court decided in Heller’s favor and the decision was considered a landmark case against gun control. It was the first time the Supreme Court had said outright that the Second Amendment guaranteed individuals the right to bear arms regardless of any connection to a well regulated militia.

Justice John Paul Stevens, who sat on the court when the Heller decision was made—and who wrote a dissenting opinion against the decision—called it “the Supreme Court’s worst decision of my tenure.” And Stevens sat on the court for 35 years.

Toward the end of this month, The Supreme Court will decide on New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, another case involving the right to bear arms. At issue is whether the state can require an applicant for a concealed weapons license to show that he/she has proper cause or need for a concealed weapon based on a specific threat (not just a fear of crime). Under the Sullivan Act of 1911, to get a concealed carry permit, New York State residents must “demonstrate a special need for self-protection distinguishable from that of the general community or of persons engaged in the same profession.” Plaintiffs in the pending case claim the law is unconstitutional and violates the Second Amendment. This is the first gun rights case the Supreme Court has heard since the Heller case and the decision will have a broad impact on whether local and state governments can set their own regulations. Both sides of the issue will be watching closely.

Gun control already exists in America and has existed since our founding. In 1786 Boston prohibited the storage of a loaded firearm in a residence. In 1878, one of the first laws Dodge City passed in its heyday as an unruly frontier town was the prohibition of carrying firearms within the town. Thousands of other local governments since have written their own statutes.

Owning a fully automatic weapon such as a machine gun is not banned outright but so heavily regulated that owning one is effectively prohibited. In Colorado where I live, large-capacity magazines are prohibited. Under the statute, large-capacity magazines are defined as those holding more than 15 rounds of standard ammunition or more than eight shotgun shells. (Only nine states regulate high-capacity magazines).

But throughout most of the country, on their 18th birthday, a boy or a girl can waltz into a gun shop and buy an assault rifle, nearly unlimited ammo, and large-capacity magazines with no prior training and next to no psychological or behavioral screening. Here are some things you can’t do in America at that age: buy a six-pack of beer in a liquor store, buy a pack of cigarettes, play blackjack or roulette in Las Vegas.

Here is something you can’t do without a written and practical test: drive a Prius or any other car for that matter. There’s good reason to have an age limit on drinking and smoking and gambling and there’s good reason to require a kid to pass a rigorous test before handing him/her/they the keys to a 3,000-pound vehicle. But due to some distorted beliefs about the second amendment, some Americans seem okay with 18-year-olds buying assault rifles as casually as buying a pair of jeans.

I can’t imagine the pain of the families who lost their children in Uvalde and I won’t even try. I don’t think sending “thoughts and prayers” does them much good. The politicians who sent their boilerplate thoughts and prayers and then two days later spoke at the NRA conference in Houston, took cynicism to a level even Nicolo Machiavelli could appreciate. It was Machiavelli who said, most cynically, “There is nothing more important than appearing to be religious.” For the craven politicians, there is nothing more important than appearing to be shocked and grieving after a mass shooting despite accepting millions of dollars from the NRA.

The framers of the constitution had good cause to write the Second Amendment. During the revolutionary war, it was the militias composed of farmers and townsmen—pretty much all men of fighting age—who fought off the British. They were not professional soldiers and early Americans feared standing armies composed of professional soldiers as they represented tyrannical authority. It was the British standing armies that had brought so much suffering to colonial America. To American revolutionaries, there was a reverence for the ideal of militias—men ready to fight but composed of men from all walks of life. To have effective militias meant guaranteeing a right to bear arms for those in the militia, hence the Second Amendment.

But it’s hard to imagine that the framers could imagine two centuries henceforth the bloody massacres we see today in America by men armed with weapons bought under the guise of the Second Amendment. Hard to imagine James Madison witnessing what happened in Uvalde and saying to himself, “The Second Amendment protected the freedom of that eighteen-year-old to buy an assault rifle and hundreds of rounds of ammo…even if he subsequently killed 19 children.”

There’s a Scottish joke about a tourist who stops to ask a local for directions. The tourist asks, “How do I get to Aberdeen from here?” The local responds, “Good lord, if I were going to Aberdeen, I wouldn’t start from here.” The joke suits our present situation and conversation about guns and mass shootings. If the last 15 years are any evidence, then starting “here” with the same approach won’t get us to Aberdeen or to any sort of America where people feel entirely safe sending their kids to school, visiting their church, mosque, or temple, shopping for an iPhone at a mall, going to a nightclub, or even walking their dog in a public park.

Maybe it’s time for entirely new questions about how to achieve an old American ideal. One of the precursors to the Declaration of Independence—which included language obviously borrowed by Thomas Jefferson—was written by John Otis in 1764. He wrote,

The end of government being the good of mankind, points out its great duties: It is above all things to provide for the security, the quiet, and happy enjoyment of life, liberty, and property. There is no one act which a government can have a right to make, that does not tend to the advancement of the security, tranquility and prosperity of the people.

If every school in America is considered “a soft target” that needs to be “hardened” by armed teachers and bunker-like fortification then our local, state, and federal governments are failing their most basic responsibility. There is no “security” or “quiet and happy enjoyment of life” if our society continues to morph into a version of Grand Theft Auto or a version of Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road.

We are following what to me is a gross misinterpretation of the Second amendment, stubbornly forgetting about the “well regulated” bit in the first clause. It is taking us down a path toward a society where no one feels safe. When every 18-year-old with a grudge can walk into almost any gun shop and leave with an assault weapon, hundreds of rounds of ammo, and high-capacity magazines we are ironically conceding the very freedoms that Second Amendment zealots claim to be protecting.

We are following what to me is a gross misinterpretation of the Second amendment, stubbornly forgetting about the “well regulated” bit in the first clause. It is taking us down a path toward a society where no one feels safe. When every 18-year-old with a grudge can walk into almost any gun shop and leave with an assault weapon, hundreds of rounds of ammo, and high-capacity magazines we are ironically conceding the very freedoms that Second Amendment zealots claim to be protecting.

What freedom is there in a society where dropping your child off at school to learn the alphabet also means risking their life?