by Mary Hrovat

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones.

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones.

To the mysterious front-yard stone

For a couple of years, when I was a very small child, you were part of my everyday life in southern California. I remember you as gray and white, granular, maybe a little sparkly. You rose unexpectedly from the front lawn, a small, more or less rectilinear interruption of order. You seemed to be made for children to sit on or around, a little stony chair or small narrow table.

We were lucky; no one else had a stone in their lawn. I don’t know why you were there; I assumed that you were too big to be moved. At the time, you were an everyday part of my world, like the trellised back porch permanently enveloped in gentle green shade or the peach and plum trees growing in the back yard.

I see from street view on Google Maps that you’re not there any more. The house has also lost that porch and those fruit trees, which were replaced with a swimming pool surrounded by concrete. Well, we moved out of that house more than 50 years ago; it’s bound to have changed. Still, I would have guessed that you would outlast the house and everything else on that lot. I suppose you weren’t as large or immoveable as I thought you were, and someone got tired of mowing around you. I wonder now how you came to be there and where you went. I hope you’re still yourself, whatever and wherever you are.

To the red rocks of central Arizona

The first time I remember seeing you, I was a teenager. I hadn’t yet learned to appreciate the subtle beauty of the desert. I was enamored of the landscapes I read about in English literature, or more precisely, a stereotype of a certain subset of these landscapes, lush and green, well-watered and tidy. I’d also absorbed my parents’ memories of their home state of Ohio, and I saw the desert as an aberration, even though I was born and spent much of my childhood there. I thought that truly beautiful places were soft and green and someplace else.

The only thing I knew about you when I first saw you was that your gorgeous colors—rose, ochre, vermilion, maroon, brick—are those of iron oxide. I had no idea rust could be so beautiful. I was delighted to see a place so dominated by these vibrant colors; I hadn’t known such a thing was possible. It was as if Earth had burst into song in the land around Sedona. You helped open my eyes to the beauty of the state where I was born.

To a raindrop-marked piece of sandstone

I’ve seen you twice at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. The first time, I was visiting with a group of astronomers in training, back when I was a student. You stopped me in my tracks because the rippled, dimpled pattern on your orangish-tan surface reminded me so vividly of a Florida beach I was familiar with at the time. Your display label told me, however, that the dimples were thought to be marks from raindrops that fell 800 million years ago. Rain apparently fell in very shallow water in what is now northern Arizona, near the shore of an inland sea that covered that part of the world. The tide came up, and sand covered the pockmarks and the ripples formed by waves, preserving them.

I’d grown up without learning much of Earth’s timescale, and the first time I saw you, I was in the early stages of making up for that lack. You were one of the most beautiful and personally moving pieces of Earth history embodied in stone that I’d ever seen. I’ve changed so much since I first saw you in 1987; the years since then are a negligible flicker of time in your existence and a significant proportion of mine. I’m so grateful that our timelines overlapped.

To a slab of banded iron rock

I knew your story before I first saw you. Your distinctive pattern of dark gray and red rock reflects the introduction of oxygen into Earth’s atmosphere when photosynthesis first emerged in plants several billion years ago. The oxygen reacted with iron in solution in seawater, and the iron was deposited in sedimentary rocks (in your case, about 2.7 billion years ago). The dark rock is mainly magnetite, and the red rock is colored by very small particles of iron oxide. The alternation of the bands might be the result of seasonal variations in the oxygen content of the atmosphere.

I met you at the American Museum of Natural History. I also saw gemstones glowing in artfully spot-lit cabinets in a dim room, but you were the star of my visit. I wondered if visitors were allowed to touch you. You were far too large to be enclosed in a cabinet; unlike the gemstones, you were humbly standing in the open for anyone to approach. I hesitated and then reached out a hand. I was 42, with a maximum lifetime of maybe twice that, and I was trying to touch a history too deep for me to encompass even in imagination: a mayfly that lives for a day, trying to grasp the essence of an entire year.

To Thoreau Rock

You can’t be found on any map, and only a few people on the planet know you by that name. You’re a flat rock perched above McCormick’s Creek; your surface is about the size of a large tabletop, which makes you a good place to sit. You’re a peaceful oasis where I love to read, or watch the trees and sky, or maybe talk quietly with a friend. In the fall, I try to get out to you to read from Thoreau’s essay “Autumnal Tints.” Your surface feels chilly and often a little damp; I usually visit you in fall and winter, but you’re also a cool refuge in summer. You’re part of a beloved limestone-dominated landscape, but I’m not sure of your exact composition. I like to lay a hand on your surface in greeting and farewell.

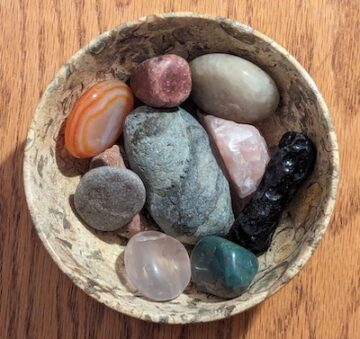

To the rocks in my house

You know, there are more of you than I realized. Some of you are mementos, picked up on a canoeing trip or a hike. Some of you are polished rocks that came into my life through a rock, gem, and mineral show that used to be held here. These include three urns, a plate, and a small bowl made of a lovely creamy brown limestone from Pakistan that contains fossils of sea creatures. Some of you were gifts: a geode given as a housewarming present more than 30 years ago, a Petoskey stone a friend brought back from Michigan last summer (containing fossilized coral from a long-gone ocean), beads of polished rock given very recently. In addition to the geological time you represent, you also carry bits of my lifetime. I’m glad you’re here.

To the limestone of southern Indiana

I don’t think I even knew the term karst topography when I moved here more than 40 years ago. I knew there were quarries here (I’d seen the film Breaking Away not long before I moved here), but I had no idea how many different limestone formations there are and the extent to which limestone has shaped the history and economy of south-central Indiana. I didn’t know that Indiana’s limestone and sandstone formed about 300 million years ago, at the bottom of a shallow sea that once covered the central U.S.

Most importantly, I had no idea how familiar and beloved your landforms and features would become to me: caves, subterranean water that erodes rock as it trickles through it, springs where this water emerges at the surface, the many sinkholes and steep ravines in the local woods, geodes and crinoid fossils.

I think and write about you as I do about all these other rocks, in terms of your connections to human lives and the human terms we apply to you. Like many others, when I think about broadening my relationship with the natural world, I tend to think of expanding the human world to greater awareness of nonhuman elements: flowering plants, animals, trees, stones. When I try to sense, even dimly, the timescale of rock and stone, I’m trying to shift my framework away from the anthropocentric; to paraphrase Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, I’m trying to see myself as nonlithic.

∞

I’m grateful to Anna M. Domitrovic, mineralogist emeritus at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, who in 2005 answered my email asking for information about the rain-marked sandstone I remembered seeing 18 years earlier. She described the rock and sent me the text from the display containing it. Museum and library staff are the best.

∞

You can read more of my work at MaryHrovat.com or in my free newsletter, Slow Quiet.