by David J. Lobina

—Is it your view, then, that she was not faithful to the poet?

Alarmed face asks me. Why did he come? Courtesy or an inward light?

So Joyce imagines in the interior monologue of Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses, as I discussed in What Joyce Got Wrong. Is it a psychologically plausible rendering of Stephen’s thoughts, I asked at the time, and answered in the negative because of linguistic reasons – in this occasion I would like to discuss some recent psychological investigations of the matter. But how can a private event such as inner speech be scientifically studied at all?

Imagine the following situation. You are about to cross the street and see a car coming; you stop on your tracks and realise there’s some space between the incoming car and the next one, enough in fact for you to rush to the other side safely once the first car has passed you. But as you start crossing the road something you are carrying emits a sound, a beep, you may even feel a vibration. It’s not your phone. It’s a device you are carrying as part of a experiment you have agreed to take part in. As soon as you hear the beep you need to stop what you are doing and write down your (subjective) experience immediately prior to the beep. You have to describe what you were experiencing at the time, whatever it was.

The idea is for participants such as yourself to take notes of their experiences at random intervals – typically 6 times within 24 hours – and then undertake a detailed interview with researchers soon after in order to produce a faithful description of the reported experiences.

Known as Descriptive Experience Sampling, this methodology requires a fair amount of training of both participants and interviewers in order to avoid possible preconceptions and confabulations and thus focus exclusively on the experiences themselves. The reported experiences are certainly varied, from inner speech and visual imagery to the sensation of having experienced thoughts that did not manifest in any particular medium, but the methodology is supposed to get to the bottom of things in any case.

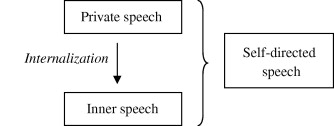

This particular method is but an example of how far research on inner speech has advanced since the turn of the last century. It has also received plenty of attention in recent years, and perhaps it will fare better than some previous psychological approaches to this research question (say, the behaviourists, or Lev Vygotsky’s take on this).

It is hard to say, not least because it has been used almost exclusively by its developers, Prof. Russell Hurlburt from the University of Nevada along with his team and colleagues, and this is problematic in itself. After all, the sure test for any experimental technique is for it to be easy to use by other researchers and the results to be replicable. It is unlikely that other researchers would find no issue with any of the choices Hurlburt and colleagues have made regarding the training of participants and interviewers, especially as it relates to the sort of questions to ask and how (not) to lead participants. More importantly, the results are very unlikely to be replicable or even robust, as they happen to be interpretations of interviews conducted in a particular way, and neither the interpretations nor the scripts the interviewers follow are likely to go uncontested.

This is not to say that there isn’t any common ground in the study of inner speech. Most people will agree that inner speech is rather similar to outer speech in that they seem to have the same sort of grammatical form, including what they sound like, or would sound like. Further, the brain regions that are activated when speaking to others are also activated when we speak to ourselves, and aphasias that affect the production of overt language can impact inner speech too.

There is a more meaningful commonality between inner and outer speech, one that hasn’t received as much attention from philosophers and psychologists. It involves an important point linguists have made in the past regarding the production of language in general. So what does the linguist have to say about inner speech?

The right sort of linguist would, first of all, stress the different facets there are to language, starting with the question of what language itself is. By “language”, as I have often discussed at 3 Quarks Daily, I don’t mean a particular language such as Latin or the act of communicating through voice (speech), but a system of signs considered in the abstract – language as a capacity, as in humans have language and animals don’t. The three constructs – a capacity, a particular language, and speech – are naturally related and all three are part of the dictionary entry for the word “language”, but they shouldn’t be conflated.

The question of what language itself is also exercised the curiosity of the ancients, and in fact most linguists today subscribe to the old Aristotelian idea that language is sound with meaning (though Aristotle didn’t quite put it in these terms). What is usually meant by this is that some of the sounds we emit carry meaning, they express something, from ideas and feelings to commands and arguments. What’s more, it is our intention for such sounds to carry meaning, for it is generally our intention to communicate our thoughts when we speak.

The connection between sound and meaning is a central topic of research in linguistics, a connection that in the case of sentences is mediated by syntax – i.e., by the way a sentence is put together and how its words relate to each other, hierarchically. But we obviously do not speak in hierarchies, and nor do we hand-sign them (sound is a generic term and not meant to exclude sign languages from the definition of language).

How are hierarchies used? In the most common case, the hierarchies are produced in speech, but for this to happen they must be “linearised”, as the organs we use to speak can only produce segments one by one (the same goes for hand-signing). What I mean by this is that hierarchical structures need to be converted into strings of words (or hand gestures) in which words appear in a certain order, one after the other. It is these strings that we typically call the sentences of a language, linear and flat sequences of words that once generated are fed to the organs that produce them.

Whatever else they may be, both inner and outer speech (as well as hand gestures) are the result of the need to produce the structures that our linguistic capacity generates. To produce speech, then, is to turn the hierarchies that language generates into strings that can be “externalised”, as some linguists like to say, to ourselves or to others. The overall picture also suggests a number of points that are clearly relevant for the study of inner speech.

First of all, it is important to point out that the linguist’s theory is supposed to be neutral regarding the production or comprehension of language – the theory is meant to explain what language is like, not how it is used (at least not directly). Nevertheless, the picture I have painted does accord well with a well-known model of language production. In simple terms, this model has it that language production starts with the formulation of a message (a thought) to be communicated, which is then followed by the selection of the appropriate words, a way to put these words together into a sentence, and the issuing of motor commands to the organs in charge of producing the message, be this in speech or through hand gestures.

The model applies equally well to inner and outer speech, the main difference between them perhaps whether motor instructions are executed or not (and if so, which ones). Rather pertinently, it seems to be the case that what the brain encodes during the production of speech is not sound itself, as customarily thought, but the motor commands to produce speech – that is, the movements of the vocal tract (lips, tongue, jaw, etc.).

The model of language production I have described has come under criticism for being too straightforward and simple. Speech is full of false starts and changes of perspective, and as a matter of fact we don’t always express whatever message we initially entertain. There is also some evidence from the field of psycholinguistics that hearing your own sentences as you utter them has an effect on what you say next. That is, language comprehension, often described as a phenomenon in which we receive linguistic input and recover its meaning, would affect what at first sight would be the opposite phenomenon, language production.

Some philosophers have taken this point to heart.

The philosopher Peter Carruthers, who has written a fair amount, and variously, about inner speech, has argued that inner speech may have specifically arisen in evolution to enable the rehearsal and evaluation of overt speech actions. Carruthers’s case is partly based on the psycholinguistic evidence I have alluded to, and partly on the assumption that the sentences of language receive meaning (or content, as philosophers call it) when they are interpreted by hearers in context. In the case of inner speech, as both Carruthers and his former student Keith Frankish have pointed out, the sentences would be interpreted by the speakers who utter them to themselves.

I suppose (some) speculation is unavoidable in the construction of evolutionary scenarios for mental abilities such as language and speech, but in this case the argument doesn’t stand on very solid ground. In particular, Carruthers takes the evidence from psycholinguistics too far and far too seriously – there is no consensus in the literature as to how widespread the effects of comprehension on production are or what the evidence actually says about the connection between these two processes. It is a hotly debated topic, in other words.

In any case, the evidence is perfectly compatible with the model of language production I outlined. False starts and changes in what you are saying may simply point to the adjustments speakers commonly carry out in order to put the message across in the clearest possible way – or it may in fact point to the very plausible possibility that one doesn’t stop thinking when producing a sentence. Indeed, it is very doubtful that one has a thought and then speaks it machine-like, as if one stops thinking while in the middle of speaking – surely to be speaking is not to be in the mental vacuum of a parrot. If you change your mind as you speak, this is reflected in the fact that often you don’t continue saying what you were saying.

Carruthers has put forward another idea on what inner speech does, one which Frankish also fraternises with. This is the proposal that the meaning of inner speech sentences, once interpreted, may be “broadcast” to other mental abilities such as problem-solving, effectively using language as a vehicle to set in motion a thinking process. This hints at a more qualified view of the role inner speech may play in cognition, and various philosophers have defended similar ideas.

Frankish, for his part, associates speech to psychological theories of reasoning, specifically to thinking that is intentional and conscious, known as Type 2 reasoning, which Frankish sees as being largely language involving (this is Frankish’s own take on Type 2 reasoning, though). According to Frankish, problem solving is often a matter of breaking down a problem into sub-problems, and this is typically conducted in a questioning and prompting manner in language, much as one does when questioning a friend in a social context. Frankish uses the example of how we may come to decide whether to go to a party we have been invited to, an event that might well start in inner speech by literally self-questioning ourselves “do I want to go to the party?” (surely this is more typical of a job interview, though). Such a question would set in motion a process of posing and answering questions, eventually reaching a conclusion – and, thus, a case of reasoning.

But I think these claims, like the position of a novelist trying to capture the inner mental life of a character, run counter to Chomsky’s point about linguistic behaviour in general – namely, the claim that language production is effectively stimulus independent, as there is no way to work out what one person will say at any one moment, or in any one situation. It is precisely the nature of the written medium that makes writers say too much, show too much of a character’s inner life – nay, create too much of this inner life, provide too many reasons, beliefs and desires, and paint people much more linguistically expressive than they really are – and this is mirrored in the views of Carruthers and Frankish on inner speech, a clear case of over-intellectualising a cognitive phenomenon.

Who can control their inner speech, after all, and how could this phenomenon play a causal role in thinking (or, indeed, in the evolution of cognition)?