by Jerry Cayford

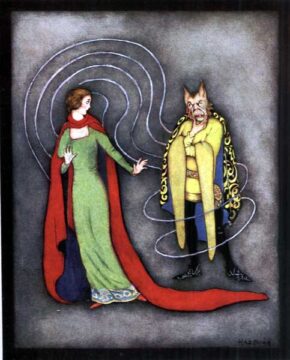

It is almost Groundhog Day again. Time for the ritual rewatching of Groundhog Day, the comically ingenious and wildly successful retelling of “Beauty and the Beast.” More than just a delightful comedy, Groundhog Day does justice to the deep psychological roots of an ancient fairy tale (“Beauty and the Beast” is, along with “Rumpelstiltskin”—about which I wrote previously—in a small group of the oldest stories in Western literature), while reinventing it for our time.

Versions of “Beauty and the Beast” differ so greatly that it is hard to find a core set of elements, or confidently identify what is or isn’t a “version” of the story. (Wikipedia has a long list.) The larger category (ATU 425: The Search for the Lost Husband, or The Animal Bridegroom) includes “Cupid and Psyche,” from ancient Greece and Rome, where the husband is a god, not an animal, and it is Beauty who is tested and must change. Some stories start with marriage instead of ending there. In “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” (Norway), Beauty marries the white bear and only sees her husband as a beast by day. In the dark, though, he comes to her bed as a man, so long as she does not attempt to see his true form.

These tales are tales of alienation between a couple who do not know each other’s secrets, and do not trust each other. They live in material splendor in enchanted castles, and are lonely. The theme is how two become one.

Groundhog Day recreates “Beauty and the Beast” with clever narrative innovations. Usually, Beauty, a paragon of virtue, is the protagonist; but an unchanging protagonist makes for a static story: all the drama, all the change is happening in the secondary character, Beast. By making Beast the protagonist, Groundhog Day brings us close to the thematic action. Another narrative difficulty it solves is how a Beast isolated in a castle has time and reason for profound psychological change. (Fans of Disney’s versions create convoluted analyses about how long the story takes and how time must move differently in the castle and the town.) By giving Beast infinite time, Groundhog Day can thoroughly detail the stages of his transformation from self-centered jerk to caring community member, plausibly earning his release from the spell.

Every version of “Beauty and the Beast” that I know of feels incomplete. The widely familiar Disney versions and Groundhog Day show only the Beast changing; Beauty is perfection from the start. The true marriage of two different entities, though, will require transformations on both sides, and most versions hint that Beauty, too, needs to change. She is evidently going nowhere, and implicitly is unsuited to marry: sometimes she is too devoted to her father; sometimes men are scared off by her beauty; sometimes her beauty is so great that the goddess Venus is offended and curses her. But something is not right with her. Excessive devotion to her family, especially her two wicked sisters, causes her to betray Beast (or to light a candle to see and spill hot wax on her sleeping husband). Disney deletes the sisters and blames society for Beauty’s poor dating choices, but the story requires some imperfection and a need for change on her part.

The softening of flaws in our main characters comes from the classic 18th-century versions of the story, especially Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s book-length 1740 telling, which Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve drastically edited to create our canonical tale in 1756. These versions seem so concerned with propriety that they insist both Beauty and Beast (aside from the spell) are really perfect in every way; the spell makes Beast hideously ugly and also dull-witted so the story can focus purely on seeing past physical charm and wit to moral virtue. They even give eye-rollingly implausible back stories to make Beauty nobly-born and Beast blameless for his enchantment. That prissiness would not sell in the 20th century, and modern versions like Disney’s and Groundhog Day know that Beast starts out beastly and justly punished.

Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film La Belle et la Bête sticks close to the canonical story yet subtly hints at deeper insights. The objects in the castle that serve Beauty—disembodied arms holding candelabras, the magic mirror—all suggest she is really surrounded by servants, but her loneliness has turned these people to inanimate objects and made the castle feel deserted. (Disney’s extremely animate objects, filled with personality, undermine this theme of Beauty’s isolation.) When Cocteau’s Beast returns to human form at the end, he looks just like Beauty’s suitor in the village; he asks and she tells him she loved her suitor (who has died trying to steal Beast’s treasure) but could not commit to him. The implication of this simple visual device is that Beast and the suitor were always one and the same, and the story is of a couple who were always together but became alienated by the husband’s indulgence of his beastly side (probably his pursuit of worldly treasure).

Expanding on Cocteau’s hints of greater psychological depth here, let’s look at the wider folktale tradition. All of these pop-culture versions have been pretty tame compared to the hard-hitting norm for fairy tales. The process of personal transformation can be brutal, and fairy tales traditionally pull no punches in portraying it. Scholars of folklore have a lot to say about this topic, and Bruno Bettelheim’s 1976 The Uses of Enchantment makes the case that the violence of folktales is essential to their function of inoculating the child against the world’s violence. A quick, witty, and wonderful introduction is John Updike’s review of Bettelheim’s book in the New York Times, (digitally archived), beginning with this pithy Bettelheim summary: “Each fairy tale is a magic mirror which reflects some aspects of our inner world, and of the steps required by our evolution from immaturity to maturity.” However outward the stories’ action, the inner aspect is always key.

In Apuleius’s 2nd-century story “Cupid and Psyche,” a much older version of “Beauty and the Beast,” the names alone tell us that this ancient tale concerns the inner forces and workings of the mind. Cupid is eros, our creative and erotic force, and Psyche is, well, psyche: mind, soul, spirit. All of these stories are about the unification of our beastly erotic nature with more civilized passions within us. Apuleius draws on Greek myths from a few centuries earlier, which brings us to the inescapable Plato. In keeping with the truism that all of Western thought is a footnote to Plato, any reading we make we read through Plato. Reading “Beauty and the Beast” through Plato, though, shows an especially interesting twist.

Plato’s famous metaphor of the human soul as a chariot has three parts (I’ll use John Uebersax’s description, where you can find much more): “a charioteer (Reason), and two winged steeds: one white (spiritedness, the irascible element, boldness) and one black (the appetitive element, concupiscence, desire).” This image comes to us rewritten by Freud as the ego, the super-ego, and the id. For our purposes, the point is that Beast is the black horse id, and the story is of white horse Beauty’s taming and conjoining the beast to make an integrated whole, one being, a true synthesis. The Freudian revision of Plato seems to match our modern idealization of Beauty: she has to be perfect to suit our sensitivities. That is, we have remade her as super-ego. Put that way, we haven’t progressed much from those 18th-century pieties, and the story doesn’t cut as deep as it should. Plato’s white horse, however, is more passionate, complex, and energetic—more partner and companion horse than charioteer—and points us toward better readings of “Beauty and the Beast.”

The allegory of the charioteer is not original to Plato. As Uebersax says, “The myth itself is not Plato’s — it was ancient even for him, perhaps coming from Egypt or Mesopotamia — but he adapted and reworked it.” In thinking of Beauty not as cold perfection or chastising super-ego taming the Beast (how many times does Rita slap Phil in Groundhog Day?), but rather as “courage, boldness, heroism, ‘spiritedness’ and what some call the irascible” (Uebersax), I can’t help thinking of a somewhat different story as, again, “Beauty and the Beast.” If ever there was a writer as capable as Plato of reworking ancient folktales into complex and nuanced dramas of the human condition, it is William Shakespeare. And that “irascible” sounds very like Katherine—“called plain Kate, And bonny Kate, and sometimes Kate the cursed”—in Shakespeare’s comedy The Taming of the Shrew.

Shakespeare sourced his plays sometimes from folk and fairy tales, and The Taming of the Shrew is generally considered one such. Since it is superficially most like another whole set of folktales of husband’s disciplining their wives (and then showing off their control), it is routinely categorized with those tales. Shakespeare, though, is a master of finding deeper complexities in simple stories and of weaving different sources into works transcending those beginnings. It is hardly a stretch, then, to find him dressing a deeper story of Beauty and her Beast as a simpler stereotypical one.

Part of the attraction of this interpretation is that The Taming of the Shrew is a ferociously two-sided story: the raging, brawling, witty Katherine and Petruchio both give as good as they get. If “Beauty and the Beast” (The Animal Bridegroom, The Search for the Lost Husband, Eros and Psyche) is the story of two parts transforming into a unified whole, then both parts are essential and both must adapt. If this is the deeper story of The Taming of the Shrew, then Petruchio must transform as well as Kate.

It is not hard to find Petruchio changing in the play, but it requires not being too credulous about certain elements of the husband-disciplines-wife surface. For example, Petruchio says early he will pretend to be mad, and apparently does; but if a beast says he’ll pretend to be a beast, it doesn’t mean he is NOT a beast. Likewise, in the (infamous) last speech of Katherine, she claims to be a submissive wife. Various circumstances complicate that message, such as its being the longest speech of the play and full of complex, self-confident analysis, as well as being preceded by her dragging the other wives in by their ears; the fact that the other marriages are far from male-dominated also complicates any misogynist reading. Most importantly, though, the thesis of “Beauty and the Beast,” that two parts can become a single whole, does entail that each part becomes subordinate. In this way, Katherine’s speech is serious, but her subordination is to the true marriage Shakespeare is depicting, not to some separate and dominating individual outside herself.

The Taming of the Shrew, especially in the broad, physical, commedia dell’arte style often employed, can seem as brutal as fairy tales typically are. Modern audiences like a lighter touch, and we edit out violence and simplify the story. That’s okay. A gentler story can get the message across. The 1951 film The African Queen has a wonderfully light touch, and still it is both “Beauty and the Beast” and The Taming of the Shrew.

I can forgive Groundhog Day for simplifying the Beauty side of the story because I don’t forget there are two sides, and it tells Beast’s story in so much more depth than any other version I know. “Beauty and the Beast” is notoriously sketchy on why Beast is cursed. (Probably that 18th-century reluctance to admit a princely Beast is bad.) Versions that do give a reason (such as Disney’s) are pretty cursory and generic: arrogant and selfish, the prince pissed off a witch. Groundhog Day says nothing whatsoever about how Beast’s absurd situation came to be. But while it leaves the fairy tale magic unexplained, it has an evocative and tragicomic scene with something to say about the very human nihilism underneath beastliness. It’s the scene with the two drinking buddies, the scene that launches Phil on his hedonistic phase:

Phil: “What would you do, if you were stuck in one place, and every day was exactly the same, and nothing you did mattered?”

Bar guy: “That about sums it up for me.”

Stripped of magic, beastliness appears as something ever present, not to be vanquished forever by a kiss or a declaration of love, but worked at steadily, like a true marriage. (Johnny Cash’s rendition of “The Beast in Me” nails it.)

Groundhog Day, for all its depth and wit, is just a beginning, a wonderful part of a larger story. My pleasure in the movie is enhanced by the rich tradition of fairy and folk tales—and theatre and philosophy—from whence this great comedy came.