by Tamuira Reid

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

Ugh, she sighs, wiping away the lip pencil I just watched her carefully apply for over the better part of an hour. This color, what is it? Hot-rod red? More like hotdog orange. Fuck you, MAC.

Grabbing a lighter shade from her stash of pencils, Sam regroups, starts over.

Music plays from an open laptop in the corner, haphazardly balanced on a milkcrate-turned-nightstand, The Weekend telling us to save our tears for another day. A beam of late afternoon sun finds its way through the cracked blinds, illuminating the side of Sam’s pale face.

You’d think I’d be better at this by now, she laughs, shaking her head, chestnut curls bobbing up and down at her shoulders.

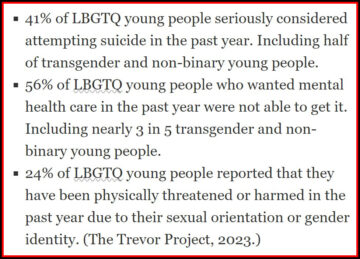

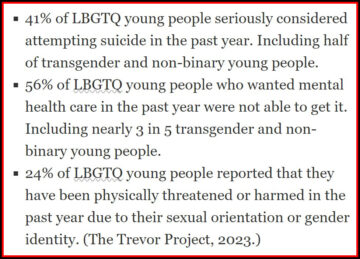

The first lip pencil she used was stolen, straight out of mama’s make-up drawer, when Sam was just seven. She hurriedly ran into the bathroom and locked the door, giddy and nervous af. A small compact mirror in her lap. Cold tiled floor beneath her. There was a freedom in that moment for Sam, the kind of freedom that comes with spectacular acts of defiance. A girl doing girl things, because to the rest of the world, including her own family, Sam was very much a boy.

I was scared. Had a lot of shame back then. It was paralyzing. I knew my gender didn’t match my biological sex. I knew I was a girl. But I didn’t have the words to explain this to my mom and my brother. To anyone. It was a secret I held onto for a long time and it hurt. A lot. Read more »

Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2011- …

Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2011- …

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

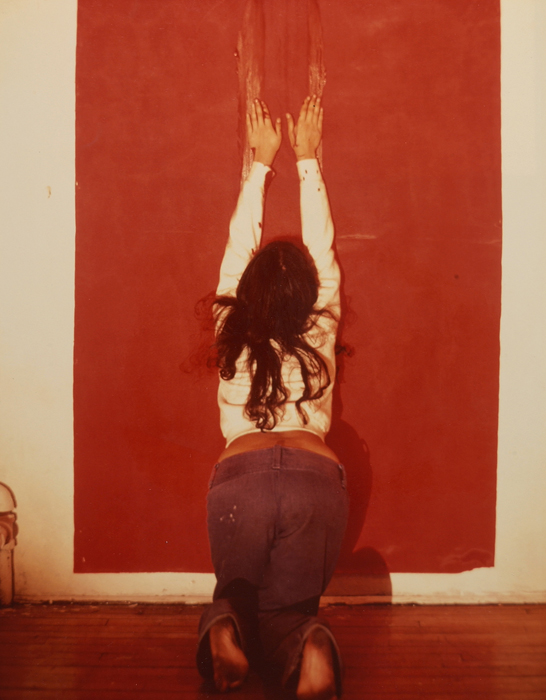

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.

I recently binge-watched all of

I recently binge-watched all of

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.