by Jeroen Bouterse

Several years before C.P. Snow gave his famous lecture on the two cultures, the American physicist I.I. Rabi wrote about the problem of the disunity between the sciences and the humanities. “How can we hope”, he asked, “to obtain wisdom, the wisdom which is meaningful in our own time? We certainly cannot attain it as long as the two great branches of human knowledge, the sciences and the humanities, remain separate and even warring disciplines.”[1]

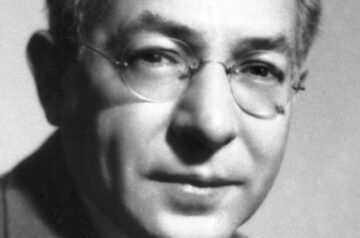

Rabi had been interested in science since his teenage years, and grown up to be a Nobel-prize winning physicist. He had also been an important player in the Allied technological effort during World War II, as associate director of the ‘Rad Lab’: the radiation laboratory at MIT that developed radar technology. The success of Rad Lab, Rabi later reflected, had not been a result of a great amount of theoretical knowledge, but of the energy, vitality, and self-confidence of its participants.[2] In general, Rabi’s views on science and technology were somewhat Baconian: science should be open to the unexpected, rather than insisting on staying in the orbit of the familiar.[3]

‘A moralist instead of a physicist’

In Rabi’s accounts of his time leading Rad Lab, he would also emphasize the way in which he insisted on being let in on military information. “We are not your technicians”, he quoted himself, adding: “a military man who wants the help of scientists and tells them half a story is like a man who goes to a doctor and conceals half the symptoms.”[4] Indeed, the key to understanding Rabi’s worries about the two cultures – he would go on to embrace Snow’s term – is his view of the role science ought to play in public life. Scientists should not just be external consultants,[5] delivering inventions or discoveries on demand or listing the options available to the non-specialist.[6] In some stronger sense, they should be involved in directing policy decisions.

Even more than Rabi’s positive experience with the military during the war, his views were informed by his frustration with the lack of agency scientific experts were able to exercise in the immediate aftermath. Already in 1946, he complained in a lecture that scientists had been used to create the atom bomb, but they had not been consulted about its use, and the fact that many of them had been opposed to it had made no difference. “To the politician, the scientist is like a trained monkey who goes up to the coconut tree to bring down choice coconuts.”[7]

This feeling would increase with the decision to develop a hydrogen bomb. In 1949, Rabi was one of eight experts in the General Advisory Committee (GAC) to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), in which capacity he co-signed a unanimous report arguing that the ‘Super’ should not be built. (Rabi, together with Fermi, signed a minority opinion to the effect that the US should first get the USSR to pledge that it would not seek to develop an H-bomb.[8]) Rather than signaling to the world that he sought to avoid an arms race, however, President Truman did the opposite: without knowing that it was even possible, he announced publicly that the US would “continue its work on all forms of atomic weapons, including the so-called hydrogen or super-bomb.” Rabi would never forgive Truman.[9]

The opinions of the scientists could and should have carried more weight. “We just wrote our report and then went home, and left the field to the others”, Rabi reflected later. “That was a mistake. If we hadn’t done that, history might have been different.”[10] About Truman, he said that “he simply did not understand what it was about … He didn’t have his scientific people to consult and give him an impartial picture.”[11]

What was it that Truman didn’t understand, though? Of course, there were judgments to be made as to whether the program would succeed, and as to whether the Soviet Union could develop the H-bomb if the US didn’t. However, the GAC report to the AEC focused mostly on the scale of destruction the H-bomb would deliver. It argued that bringing such destructive power into the world would be bad, and that it would have a negative effect upon the standing of the US in the world. One would think that all of these considerations were understandable to Truman. It is clear why Rabi believed the President made a foolish decision; it is not so clear why he thought this decision rested on a misapprehension of the science.

However, in the context of Rabi’s broader thinking about science in modern culture, as he came to develop and express it in the decades after the war, this judgment makes a lot of sense. The point was not just that more technical expertise needed to be brought to the decision tables; the point was that scientists should make their moral views heard. In the atomic age, where science created so much power, science’s representatives should wield some of that power. From the perspective of the scientists, this was because the atom bomb had demonstrated beyond doubt that science was not (or not just) a disinterested search for objective truth; it had consequences, and scientists should accept responsibility for those consequences.[12] They should consider not only the means, but the goals.

That implied they had something to say about goals, and indeed, they had. Commenting on President Eisenhower’s appointment of a Commission on National Goals, Rabi said that such goals are not the kind of thing you find by looking for them directly; goals are immanent in certain kinds of activity. Science was one such kind of activity. “I am becoming a moralist instead of a physicist”, Rabi admitted.[13]

You have been getting a good deal of that as scientists are drawn into public affairs. Instead of being coldly expert, they become moralist. They speak of values; they define goals. Indeed, they are the opposite of the popular image of the scientist as cold, keen, and aloof, insensitive to feeling and to the color and tragedy of the human condition.

Scientists were able to bring their own perspectives to questions of value, because science was all about caring about truth and understanding, about finding meaning. Rabi came to write ever-more emphatically about the existence of a ‘scientific culture’, defined by its optimism in accepting the challenge of an external world that was not understood yet, but might be understood better.[14] He believed that it would be good if this culture would come to be at the center of culture broadly speaking. “If some of the customs and tradition of science could be transferred to the halls of our Congress or the United Nations, how beautiful life could become.”[15]

‘They want to be told what to do’

It is in this context that we can understand Rabi’s worries about the ‘two cultures’ of the sciences and humanities. A television interview with historian and presenter Eric Goldman illustrates the connection:[16]

GOLDMAN: Let me bring up here what troubles so many people, as you well know, namely, the feeling that science as a discipline is essentially a discipline without values, and that the great public questions are essentially questions of values.

RABI: I think that point of view is entirely mistaken. [… I]t seems to me that science is completely full of values, important social and individual values. But they are of the human, universal kind, rather than local values.

GOLDMAN: Then in this present discussion among thoughtful Americans about the two cultures, the scientific and the humanistic cultures, you do not see the chasm between them as being one in which science is a method and the humanities provide the values?

RABI: No.

A model where science was seen in merely instrumental terms, and something outside of science was supposed to deal with ‘values’, was flawed; it was the model of the scientist as a trained monkey. Rabi believed that science was a united tradition and a source of values, and that it had the potential to be at the center of culture. Other things would have to make room for it. If the humanities were being held up as a source of ‘wisdom’ that taught us how to live in a world with the H-bomb, then there was a misunderstanding to clear up about where wisdom came from.[17]

On a different occasion, Goldman passed on to Rabi and to C.P. Snow a message from his own students. Goldman’s students insisted that they needed “something which will give us some values” and would gladly leave science to the scientists. Rabi likened the desire of the students to that of Eisenhower’s Commission on National Goals. He diagnosed: “they have been so far out of tune with their age they’ve missed the vigor of science and they want to be told what to do, because they’re lost in the world and because they’ve missed the life-giving force which science has.”[18]

In a sense, Rabi was being a good historicist here: values are not just out there waiting to be discovered by a committee or handed down by an especially insightful philosopher or poet. Rather, they are to be understood in terms of the conditions of the time. In the modern world, the values required were those immanent in the scientific tradition, for the simple reason that science was shaping the world. “[T]o make a democracy work, we must first have democrats. Likewise, to control the tremendous thrust and surge to which science is subjecting our society, our whole culture must first be infected with, or sensitized to, the scientific spirit.”[19] Our own times, different as they are from the past, are to be understood by their own lights. Saying that the humanities are the only source of values “betrays a lack of self-confidence and faith in the greatness of the human spirit in contemporary man.”[20]

Like science, the contribution of the humanities lies not just in what they discover, but is also immanent in their tradition; but this tradition is conditioned and limited by its subject, which means that the humanities cannot give us everything.[21] What they can give us, moreover, is already accessible to the scientist, whereas the contributions of the scientific culture are not available to the humanist. Rabi often expressed his respect for literature and art, but he could be very dismissive about humanistic scholarship. “I would find it very difficult to name an important topic in the humanities which scientists couldn’t make a stab at”, he said in the TV discussion with Snow and Goldman.[22]

Listening attentively was the fourth discussant, the historian Reinhold Niebuhr. Niebuhr had just written a book titled The structure of nations and empires, explicitly meant to inject some historical sense into an age which saw itself as one of a kind, its challenges and conditions as unique. The book, a historical overview of the realities, rhetoric and ideology of empire, was an argument in favour of some measure of realism on the part of the US about its own status as a political hegemon and an imperial power. “We are not a sanctified nation”, Niebuhr wrote, “and we must not assume that all our actions are dictated by considerations of disinterested justice.”[23] The interplay between power and ethics was complex, and Niebuhr worried about the naïveté of idealists who disregarded this complexity.[24] Idealism can itself be an instrument of power. This is something we can see clearly in the past, in the Gregorian reforms of the medieval Church for instance, and in that way the past carries lessons for the present, for any “center of power which assumes that its disinterestedness is superior to all centers of historical power”.[25] If we ignore these lessons and assume our own conditions and ideas to be unique, we miss something.

Niebuhr showed himself very skeptical of the possibility of radical breaks in the patterns of history. He dismissed the idea, for example, that democracy had put an end to the usual self-interested calculations that led to war or peace; at best, democracies were slower to make war, but also slower to make peace.[26] Similarly, he criticized those who believed that “the same scientific procedures which were so efficacious in mastering natural forces would be equally effective in mastering the problems and perplexities of human history”, and who argued that nuclear disarmament would be achievable as long as politicians left things to scientists.[27]

Snow and Rabi both represented, in their own way, the idea that there was indeed something qualitatively new about science. Something that was not limited to technological progress, but that had far-reaching cultural and (especially for Rabi) political relevance; there was some way in which it stood above history while being capable of informing it. For Snow, scientists had ‘the future in their bones’; for Rabi, the idea that nature is understandable represented “an almost complete break with the past” that needed to be given “proper weight in the cultural and practical affairs of the world”.[28]

In the tv discussion, Niebuhr decided to push back against the idea that scientists were especially forward-looking. This optimism was warranted in the physical sciences,[29] he said, and could be extended to the alleviation of global poverty (a major topic in Snow’s lecture on the two cultures) to the extent that this was a technical problem; but it did not translate well to the political realities of the Cold War. In “the world of power”, it was clear that human nature was recalcitrant and historical patterns were unwieldy. The methods of physics could not simply be transferred to the human scene.[30]

Rabi’s reflexive response was – “But you have to do that”. He followed it up, however, by a second thought: “Yet you can’t do it simply because political science doesn’t solve political problems in the way that physics solves the problems of nature.” He was, in fact, himself ambiguous about non-natural science. He did sometimes consider it as relevant expertise on which policy-makers should rely;[31] but he also saw the inclusion of social science in the President’s Science Advisory Committee as a big mistake. It spelled “the beginning of the end” for an institution in which Rabi had been very invested: social scientists would have not have the same authority over self-confident senators that physicists had, and “what the social scientists have to contribute to social questions wasn’t fresh”.[32]

‘A just and meaningful world’

It is a soft law in two cultures discourse that precisely those who most bewail the chasm between science and the humanities end up deepening it. In Rabi’s case, the reason is that he believed in the two cultures; he believed there was something special about the culture and tradition of modern natural science that was a source of wisdom and strength, and that in many ways the project of the humanities was its opposite. Understanding of nature was progressive and forward-looking, was a matter of hope and optimism, while understanding of the human world was old, had already been achieved in ancient societies, and was more a matter of transmission than of innovation.[33] Historian of physics Michael Day notes that over time, Rabi talked less about merging the two traditions and more about putting science at the center of education.[34]

This required quite a far-going essentialism about science. It is tempting, as Niebuhr did, to deconstruct such claims of radical novelty or transcendence made on behalf of science. Easy to scoff at the suggestion that politics would magically change if only it were left to experts on radiation. To the extent that a more enlightened politics is possible, it seems arbitrary to say that such a politics must be informed primarily by the study of the natural world, and not by that of history or society.

In spite of this, I think Rabi saw correctly that picturing science and the humanities as opposing forces helped him to identify a real fault line in modern culture. The notion that science has to stay on one side of the fact-value-distinction, while the humanities are closer to the actual formation of values, was not a figment of his imagination, and it did stand in the way of his cultural ideals. While not quite the synthesis between the two sides that he sometimes claimed to aim for, the answer he gave – that neither science nor the humanities, nor committees ‘discover’ values, but that values are immanent in activities, in ways of life; that the age of science came with the scientific way of life, with its own values, and that these values were potentially culture-defining – was compelling.

Rabi was not alone in his claim that “scientific truth and the scientific adventure can set the standard for our contemporary striving for a just and meaningful world”.[35] Many other intellectuals in the 1950s and 60s regarded the scientific ethos, or the norms embedded in scientific institutions, as a paradigm for a modern, free and democratic culture.[36] We saw Niebuhr’s reservations already, and there has rightly been a lot of debate about whether science could carry this responsibility; but there remains something inspiring in Rabi’s vision of a common quest for knowledge and understanding, of people working together in activities that are both exciting and important, and of a society that takes those people and their projects not as resources to be exploited, but as models to be emulated.

***

[1] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1956/01/scientist-and-humanist-can-the-minds-meet/641287/

[2] I.I. Rabi, My life and times as a physicist. Claremont College, California (1960) p. 5-6.

[3] John S. Rigden, Rabi: scientist and citizen. Basic Books Inc, New York (1987) p. 118; see also Rabi’s worries about theoretical physics disconnecting from experiment and empiricism in Michael A. Day, ‘The two cultures and the universal culture of science’, Physics in perspective 6 (2004) 428-476: 444.

[4] Rabi, ‘Science and public policy’ (1963) in: Rabi, Science: the center of culture. The World Publishing Company: New York (1970) p. 70.

[5] ‘Science and public policy’, p. 91.

[6] My life and times as a physicist, p. 6.

[7] Rabi, ‘Approaches to the atomic age’ (1946) in: Science the center of culture, p. 139-140.

[8] https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/documents/hydrogen/gac-report.html

[9] Ray Monk, Inside the center: the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Jonathan Cape: London (2012) p. 554.

[10] Rigden, Rabi, p. 208

[11] Quoted in Rigden, Rabi, p. 209.

[12] Rabi, ‘The physicist and physics’ (1945) in: Science the center of culture, p. 25-26.

[13] Rabi, ‘Science and the liberating arts’ (1962) in: Science the center of culture, p. 47.

[14] Rabi, ‘Our underdeveloped culture’ (1963) in: Science the center of culture, p. 52-53.

[15] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1951/01/faith-in-science/639505/

[16] ‘The Open Mind’, Sunday, June 17, 1962. Transcript from Rabi Papers: Box 71, Folder 3 (Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington DC). All references to the Rabi papers thanks to Michael A. Day, ‘The two cultures and the universal culture of science’, Physics in perspective 6 (2004) 428-476; and with thanks to the Library of Congress for the digital copies.

[17] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1956/01/scientist-and-humanist-can-the-minds-meet/641287/

[18] ‘The Open Mind’, Sunday, December 18, transcript Rabi Papers Box 70, Folder 12, p. 31 (comma added for readability).

[19] Rabi, ‘Science and human goals’ (1964) in: Science the center of culture, p. 116.

[20] Rabi, ‘Wisdom and science’ (1967) in: Science the center of culture, p. 32.

[21] ‘Wisdom and science’, p. 33.

[22] ‘The open mind’, Sunday, December 18, transcript p. 7.

[23] Reinhold Niebuhr, The structure of nations and empires: a study of the recurring patterns and problems of the political order in relation to the unique problems of the nuclear age. Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York (1959) p. 31.

[24] Niebuhr, Nations and empires, 79.

[25] Niebuhr, Nations and empires, 114.

[26] Niebuhr, Nations and empires, 197.

[27] Niebuhr, Nations and empires, 274-275.

[28] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1956/01/scientist-and-humanist-can-the-minds-meet/641287/

[29] ‘The open mind’, Sunday, December 18, Transcript p. 8-9

[30] ‘The open mind’, Sunday, December 18, Transcript p. 13

[31] Rabi, ‘Science and the liberating arts’ (1962) in: Science the center of culture, p. 49.

[32] Quoted in Rigden, Rabi, p. 252-253.

[33] Rabi, ‘Science for nonscientists’ (1968) in: Science the center of culture, p. 134.

[34] Michael A. Day, ‘Oppenheimer and Rabi: American Cold War physicists as public intellectuals’ in: Rosemary B. Mariner, G. Kurt Piehler ed., The atomic bomb and American society. The University of Tennessee Press (2009) 307-328: 330.

[35] Rabi, ‘Science and the liberating arts’ (1962) in: Science the center of culture, p. 47.

[36] See David A. Hollinger, Science, Jews, and secular culture: studies in mid-twentieth century American intellectual history. Princeton University Press (1996).