by Rafaël Newman

The initial syllable of the English word “island”—or rather, just its very first vowel—is descended from the Proto-Germanic *awjo, meaning “an area on the water.” The element “land” was subsequently added to differentiate the word from other inflections of the Proto-Indo-European root for water, *akwa-. Our “island” is thus cognate with its German counterpart Eiland, although these days German speakers probably prefer Insel, derived from the Latin insula, which refers less ambiguously to a land mass entirely surrounded by water and not, as Eiland can, to a territory simply suffused with water.

The “s” in our “island,” however, was inserted much later, by a process of classicizing back-formation, to associate it with its etymologically unrelated synonym “isle”: as if to establish a linguistic lineage, to give island’s humble Germanic form a noble Roman pedigree. To link it, as it were, with another, greater, more patrician history.

The desire to link islands up, to settle them down, to connect them with the mainland, is an old one. Our continents, after all, are thought to have derived from the drifting apart of an original, unitary Pangea, and perhaps we have been yearning ever since for a return to that felicitous Ur-conglomerate. “No man is an island” (or rather, “iland”), wrote John Donne in 1624. Fast forward to the Confederation Bridge, or “fixed link” that unites Prince Edward Island with New Brunswick, inaugurated in 1997, and you can trace the modern history of a venerable conviction.

There’s an even more ancient story, of course. According to Greek myth, the island of Delos had been a nomadic rock, floating around in the Ocean, until it was anchored by Poseidon, the God of the Sea, and won renown as the birthplace of the divine twins Apollo and Artemis, whose mother Leto had herself been on the run, fleeing the wrath of Hera, the wife of Zeus, the god who had raped and impregnated her. The island’s original name had been Adelos, or “hidden from view,” so its renaming as Delos, with the elision of its negative prefix, celebrated the terrain’s new visibility, its new presence—to the mainstream, to the mainland, to the main Pantheon (including that enraged Hera). To the main narrative.

But in fact, Delos had had yet another name before it was settled (down): it had also been known as Ortygia, or “Quail Island”. And this has caused some confusion, or mythic doubling. Because Delos is to this day an actual, physical place, an island in the Aegean, while Ortygia (anciently Ὀρτυγία) is also an actual, physical place, although an entirely different island, some 500 kilometers west of Delos in the Mediterranean, off the coast of Sicily. And with this synonymous appellation has arisen a parallel myth, in which Apollo was born on Delos, in the Aegean, while his twin sister, Artemis, was born on Ortygia.

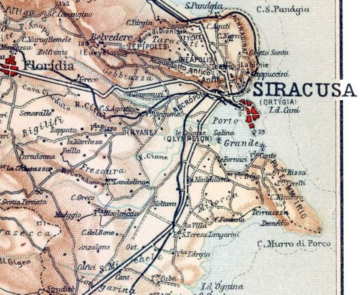

Ortigia (in its contemporary Italian orthography) is today no longer a free-standing island. What had been the historic nucleus of the Italian city of Siracusa (Saragusa in Sicilian dialect), originally the Greek colony of Συράκουσαι, or Syracuse, settled some 2,700 years ago by Corinthians from what is now the mainland of Greece, was physically linked to Sicily in the late 19th century. The twin bridges that connect it to the larger city of Siracusa to the northwest, the Ponte Umberto I and the Ponte Santa Lucia, have made the once independent island an appendage of the mainland: of Sicily, that is, as if to insist on the ignominy of Ortigia’s subjugation, since Sicily is itself an island—the largest in the Mediterranean!—and is still proudly unlinked, save by ferry, to the Italian mainland, itself a peninsula. So Ortigia now hangs in the bay like a uvula; like the Sibyl in her jar: no longer autonomous, but an element in a larger apparatus.

Nevertheless, given its long history of independence in proximity to a greater landmass, it is perhaps unsurprising that Ortigia is the site of veneration of various apotheoses of autonomy, both successfully assayed and thwarted. In addition to Artemis, the “virgin goddess” who may or may not have been born on the island and whose fondness for young women, savagery, and wildlife certainly helped her preserve her “chaste” state, at least in the compulsory-heterosexuality sense, the city is also invested by Athena, another “virgin goddess,” whose temple was built there by the Syracusan tyrant Gelo in the early 5th century BCE.

The site of Gelo’s Athenaion on Ortigia is now occupied by the Cathedral of Syracuse on the Piazza Duomo. In turn, the Cattedrale metropolitana della Natività di Maria Santissima, as the duomo is officially known, is itself dedicated to another “virgin goddess” from a later tradition—Maria, the Virgin Mary, adored in Syracuse, among other aspects, as the “Madonna della Neve,” Madonna of the Snow (or rather, “whiter than the snow,” nive candidior, as the inscription on a tomb within the cathedral maintains).

And then there is Lucia of Syracuse, the patron saint of the town, venerated as Santa Lucia there, and as variations of Saint Lucy throughout the Christian world, and whose church, the Chiesa di Santa Lucia alla Badia, stands at the end of Piazza Duomo. Lucia’s story is especially gruesome, even by the standards of conventional martyrdom: her vow of Christian chastity enraged the local pagans, and she was forced into marriage, condemned to sexual slavery in a brothel, blinded, burned alive, and stabbed to death. Caravaggio’s celebrated rendering of her burial, which is now represented by a facsimile at the Badia church, the original having been moved to the mainland, shows her corpse miraculously immobilized on the site of the future Chiesa.

The true genius loci of these precincts, however, the resident “virgin goddess” of Ortigia, her very form melded with the island’s geography, is the nymph Arethusa. The story—variously told by Keats, Shelley, Vergil, and, in greatest detail, by Ovid—goes that Arethusa (Ἀρέθουσα) had stopped to bathe in a stream in her native Achaea, on the Peloponnese, when the numinous spirit of the river, Alpheus, began to pursue her. In her despair and exhausted by her flight, Arethusa beseeched the goddess Artemis, whose attendant she was, to come to her aid, and was thus permitted to escape her Arcadian homeland—at first as a cloud and then as a stream herself, plunging under the waters of the Mediterranean, heading westward until she reached Ortygia, where she emerged as a spring.

In the course of her underwater flight (during which she spied Persephone, another victim of rape, in her own subterranean captivity), Arethusa continued to be pursued by Alpheus, who was attempting to “mingle” his waters with hers, and thus achieve his vicious aim. Indeed, Arethusa is herself referred to on one occasion by Ovid, whose Metamorphoses is a series of poems “celebrating” the etiological function of rape, as Alpheias, as if she had taken on the name of her attacker. The Fonte Aretusa, a noted tourist attraction of modern-day Ortigia, commemorates this element of the story with a bronze duo, the nymph and her pursuer united in an elegant flux of sexualized violence; the nearby Lungomare Alfeo, meanwhile, a seafront promenade along the western shore of the island, accords the mythical rapist solo honors equivalent to those granted his victim in her eponymous Fonte.

This freshwater spring, however, which rises from a karstified underground cave just a few meters above sea level, is also home to a flourishing growth of papyrus—indeed, the Fonte Aretusa, together with three nearby Syracusan rivers, is the only place in Europe in which papyrus grows naturally. A leggy riot of leaves covers much of the surface of the spring, which is also home to some diffident waterfowl. Tourists leaning over the parapet above—currently the only way to glimpse the Fonte, with construction underway on the park around it—are hard pressed to see much of its mythical waters, or to find an unobstructed space into which to toss their good-luck centesimi. Why doesn’t someone clear away all those reeds?

A ten-minute walk from the Fonte, meanwhile, on the other side of the tapering town, there is a museum that suggests the possible significance of this particular vegetation in that particular place. In an airy villa with views directly onto the Mediterranean, the Museo del Papiro houses an elaborate display of the cultural history of papyrus. Amid boats constructed of the plant from Ethiopia and elsewhere in Africa, and panels explaining the many uses to which Cyperus papyrus was put in the ancient world—to make baskets, rope, and sandals, among other useful things—there is an account of the interrupted history of papyrus cultivation in Sicily, which was recommenced, after a prolonged caesura, in the 18th century, as well as a film explaining the premodern technique, adapted from that of the ancient Egyptians, used to produce the writing medium we still call simply papyrus.

And of course, it is as paper that papyrus is best known—its botanical designation is the source of our word paper, after all—and it is in this form that it has been instrumental in the transmission of so much of what we know about antiquity, including, importantly, its mythology. And here it is now, sprouting unimpeded from the spring associated with the formerly independent island of Ortigia’s patron spirit, the nymph whose flight from her assailant in Achaea linked the ancient island colony to the mainland of its colonists (the city of Corinth was located in Arethusa’s original home). Here this blossoming stand of papyrus is now, reminding us that all the figures of thwarted female autonomy and/or fetishized “virginity,” sacred generally to the West and specifically to Ortigia—Athena, Artemis, Arethusa, the Madonna, Saint Lucy—are just that: figures, in the literary (and occasionally painterly) sense; that they have been written into existence; and that they are thus equally capable of being rewritten. Not merely in the contemporary run of philological fan fiction—retellings, some more convincing than others, of canonical Greek myth from the perspective of its sidelined female deuteragonists. Nor only in the memoirs and autobiographies currently redrafting the lives of people not so long ago consigned to muteness, or at best pseudonymous authorship. But in the everyday experience of agency on the part of newly autonomous political subjects, at liberty to rewrite their collective histories, and thus to draft their individual destinies.

The “I” in island restored, to float free again, without the heavy shackles of its terrestrial appendage; without the classicizing “s” that links it, spuriously, to an imperial past; without the triumphalist trappings of colonial nostalgia for the metropolis, the “motherland” that takes the exalted designation of motherhood in vain, obliging its real-life avatars to reproduce in the name of an imagined kinship, and in the service of a globalized project, whether martial or commercial. “No man is an island.” Perhaps: but not everyone is a man; and some of us can now aspire to (re)write ourselves as I-lands.

For MFD baba nam