According to the ancient Greek poet Hesiod, women were created for the sole purpose of punishing men. The punishment of mankind in the form of womankind was kalon kakon, or a ‘beautiful evil’ – sent by the gods for a crime committed not by man but by the Titan Prometheus. Prometheus was presumptuous enough to steal fire (symbolising knowledge) from heaven to give to mankind. Zeus, infuriated with mankind’s sudden enlightenment, punished him with ‘a bane to plague their lives’, as Jenny March says. This bane was woman.

The first woman was ironically named ‘Allgifts’. She was fashioned out of the combined talents of the Olympian gods. Created from earth and water by the great smith-god Hephaistos, she was attired and domesticated by Athena; Aphrodite gave her beauty and grace; and, finally, Hermes deposited a cunning nature deep inside her heart. Zeus delivered this beautiful, and secretly evil, gift to Prometheus’ gullible brother Epimetheus. We call this first woman by the more popular name Pandora. She brought with her a dowry – the infamous ‘Pandora’s Box’, which was actually a great jar (or pithos). In the jar were sorrow, disease and hard labour. By opening it, Pandora unleashed these evils which have been plaguing us ever since. The only thing which remained in the box, within control of humanity, was hope. This was supposed to be some kind of consolation for all the suffering that life imposes on us, as individuals and as a species.

Yet, this seems like little consolation to some thinkers. One interpretation of this entire event is that with knowledge (Prometheus’ fire) comes sorrow (Pandora’s pithos). Even Ecclesiastes 1:18 reminds us of this. To somehow reconcile the two, some philosophers have asserted that with an increase in knowledge comes the alleviation of the suffering brought about by Pandora. The greatest exponent of this was probably Socrates but definitely his disciple Plato. Socrates, as a Platonic character, says that the unconsidered life is not worth living – or, to prove the point: the considered life is worth living. Yet, why is this so?

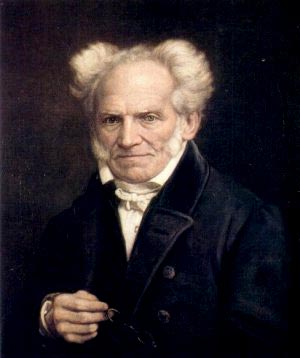

In fact, as figures like Arthur Schopenhauer and John Gray remind us, examining our life individually and human life in general, one is more likely to arrive at the opposite conclusion. Their views are this: Our world is filled with much suffering, strife and individual struggle. Our individual lives are hard – some much worse than others – and it seems that no amount of rationalising has decreased selfishness, bigotry and violence in us. We are still fearful of each other; we still quiver at the thought of death. Suffering is scattered about the world like pollen on a breeze. Of course there is no perfect way to measure human-induced suffering – but by all current measurements, for example body-count, we have in fact gotten worse (think of Nagasaki or the Khmer-Rouge).

Modern writers, like John Gray, who are taking on the mantle of Schopenhauer, say: We have used the outcomes of technology, the products of reason and the results of knowledge, to kill each other more efficiently, to induce suffering on an unprecedented scale. Knowledge of the world, how to manipulate it, is used to deliver suffering. This goes against the Socratic optimism which states that knowledge brings about a confirmation of life, making it ‘worth living’. According to Gray, this is not so.

Of course because of technology most of us are alive. For example, given that women’s bodies are so poorly ‘designed’ for labour, many of us run a very high risk of death during labour: both the newborn and the mother. The reason for this is because of our bipedal nature. During birth, a child must pass through the middle of the pelvis: because we evolved to walk on two legs, this space is narrower than for other apes. Also, newborn humans have a much larger head because of a larger brain. Humans are therefore born at a much earlier stage (any later and the head would be even bigger) and are more vulnerable, thus entirely dependent on their parents. With the larger head and narrower pelvis, the entire process is slow and painful for the mother. Thanks to medical technology, this can be alleviated somewhat and the chances of infection and death are greatly lessened. Due to the brilliance in technology and the efficiency of medically-trained doctors – both of which are outcomes of reason – mother and child have a far greater chance of surviving.

Read more »

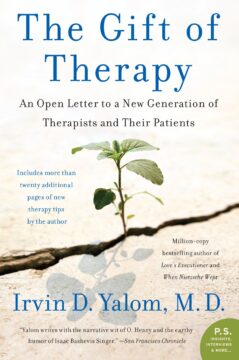

I recently binge-watched all of Group, a show inspired by the Irvin Yalom novel, The Schopenhauer Cure. So I revisited Yalom’s non-fiction to see how closely the series aligns to his actual practices.

I recently binge-watched all of Group, a show inspired by the Irvin Yalom novel, The Schopenhauer Cure. So I revisited Yalom’s non-fiction to see how closely the series aligns to his actual practices.