by Tim Sommers

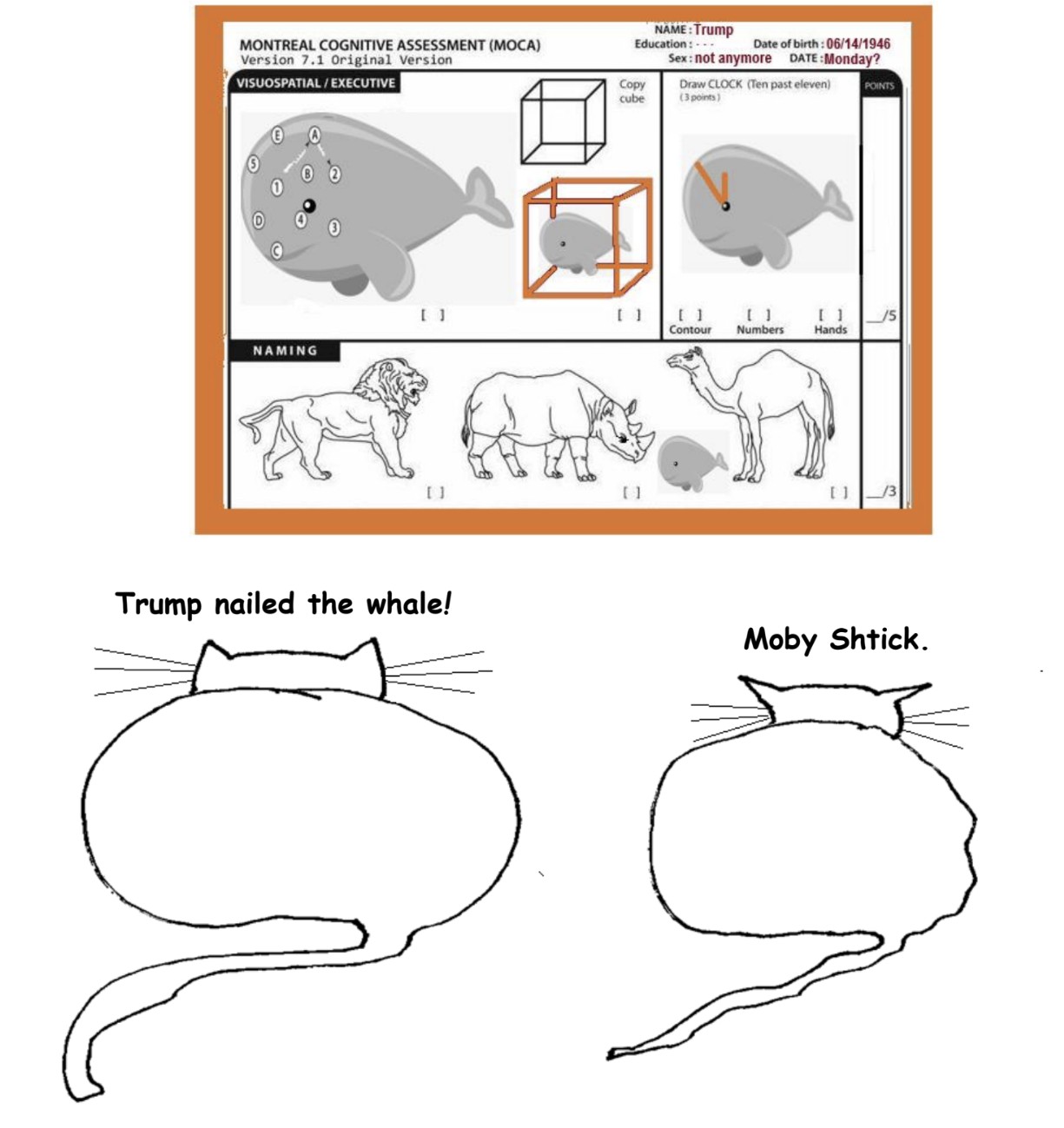

Does ignorance always excuse someone’s actions no matter how much harm they cause? If so, doesn’t that imply that the less I know about the problems of the world the less I can be blamed for them? Paradoxically, can I be a better person by remaining more ignorant? Or can I be morally culpable despite being factually wrong or ignorant about something? Either possibility seems unsettling.

Suppose malevolent aliens philosophically dedicated to chaos and destruction invade the Earth just for the sake of creating havoc and killing as many humans as they can before they move on to the next planet. As part of the struggle for survival, governments create and distribute an “alien repulsive device” (ARP). About the size and shape of a wristwatch, the ARP emits a frequency of electromagnetic radiation that discourages, but does not totally prevent, alien attacks. During the first ten months after the ARP device is distributed the authorities estimate that 200,000 lives are saved in the US alone, and a million and a half hospitalizations due to alien injuries are prevented.

Nonetheless, there is a group of people who oppose the use of ARPs. Some argue it is just a way for governments to track your movements. Others argue that the device does more harm to the wearer than is justified given that the risk of an alien assault is quite low – and the results are usually not that bad. Others deny the existence of the aliens altogether.

As a result of these views, ARP/alien-deniers spread the word to the world. Do not wear ARPs! They blog, they podcase, they protest, they try to prevent the government from handing them out by threatening or harassing public health officials. Some harass total strangers in public settings for wearing ARPs. Doctors and demographers estimate that a third of a million additional people die as a result of the alien-denialist movement, people who otherwise could have been saved.

Since this is a hypothetical, let’s just stipulate that no reasonable person could deny that there was an alien invasion, that on-balance ARPs saved lives and seriously mitigated harms, and that ARPs cannot be used as trackers. Given this, are deniers morally culpable for any of these excessive deaths? Read more »

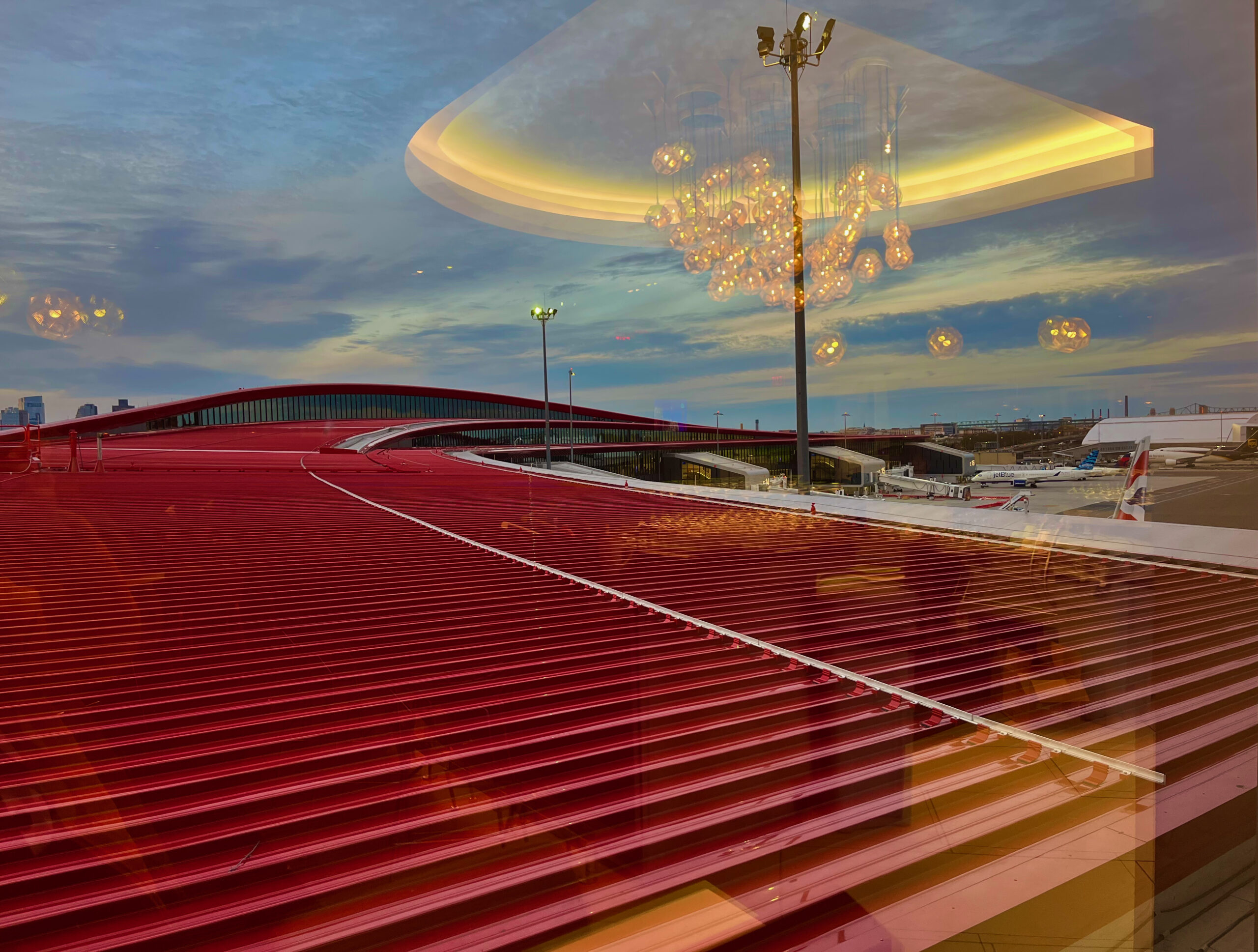

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III.

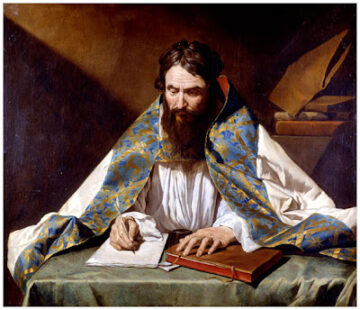

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III. As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

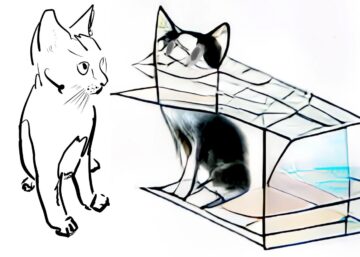

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made. I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones.

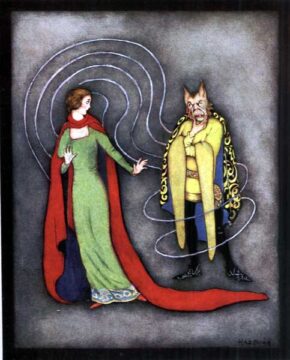

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones. Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.

Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.