by Sander Van de Cruys

If there’s one motive governing all our behavior, supervening and bringing about all our other goals or desires, what would it be? Some might say ‘survival’, pointing to Darwin’s theory of evolution. But in practice, this motive is hard to implement: It is impossible to predict or compute what, at any specific instance in time, would increase your fitness or chances of survival. It is impossible to adapt your life choices and goals to expected fitness, without getting paralyzed completely by the sheer complexity of the task —which obviously is detrimental for fitness. And if we do consider it, the motive clearly underdetermines the ways in which we pick goals and ways of life. Should I be a doctor, a lawyer, or a fricking scientist to be as ‘fit’ as I can be? The very question is absurd. Worse yet, there seem to be plenty of ways of life that blatantly go against this principle. Think about hunger strikes, vows of chastity, extremely risky occupations, or merely spending hours in computer games.

One cynical solution to this is that these are all status games. The idea is that we all want to boost our reputation in our group, and will do what gets us the rewards and recognition of our peers. Given our social nature, our fitness is closely linked to our status in our community, so we have evolved to use it as proxy that we can evaluate in the moment. I can’t help but see the current popularity of this status ‘motive’ in academic and popular-science circles as an exponent of the current online culture, prodding us to amass likes and reputation points. The message of the account is that our activities are basically empty, it is only their results that count: The reinforcements or punishments afflicted by others, who in turn have only learned to reward or punish what people like them have rewarded/punished.

The cynicism is appealing but I can’t get me to buy the content, in the wholesale way it is intended. More to the point, you know this reasoning misses something essential about our motivation, when the supposedly core target doesn’t actually feel rewarding. Any sign of an increase in status shakes me up badly, it gives me stress, instead of rewarding me to my core. Now, I acknowledge I may be atypical. I started out as a researcher of autism, and to describe that work as self-justifying would only be partly mistaken (Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t dare to accuse reputationalists of self-justification through science).

Still, if this reverse effect of status is a quirk, I don’t think it is that quirky. Read more »

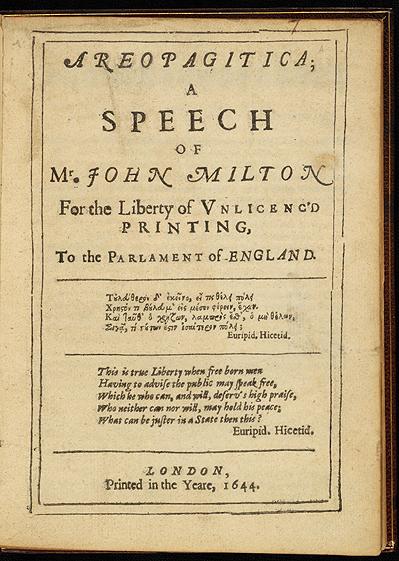

How do we regulate a revolutionary new technology with great potential for harm and good? A 380-year-old polemic provides guidance.

How do we regulate a revolutionary new technology with great potential for harm and good? A 380-year-old polemic provides guidance. Firelei Báez. Sans-Souci, (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body), 2015.

Firelei Báez. Sans-Souci, (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body), 2015.

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

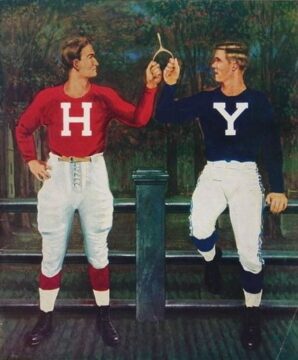

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

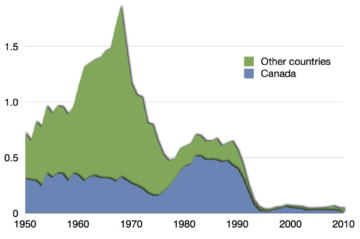

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

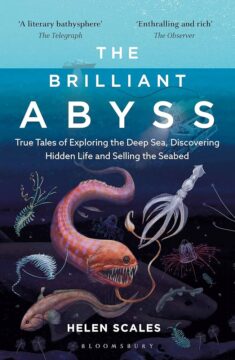

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

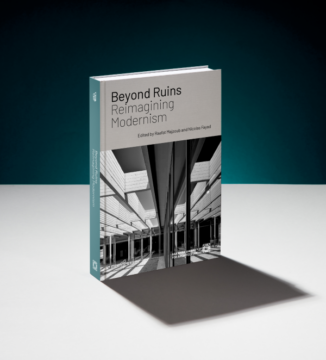

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—