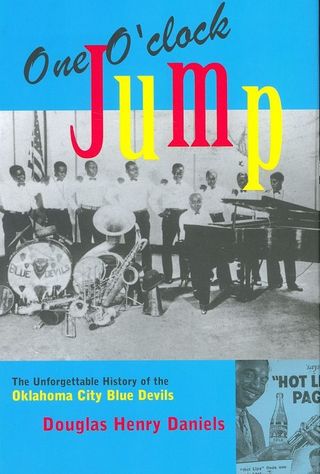

Douglas Henry Daniels, One O’clock Jump: The Unforgettable History of the Oklahoma City Blue Devils (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006, 274 pp.)

Frank Driggs and Chuck Haddix, Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop—A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, xi + 274 pp.)

by Todd Bryant Weeks

The Oklahoma City Blue Devils, the ne plus ultra of all the territory bands, still command legendary status among generations of jazz musicians, scholars, critics, and collectors. The band’s undiminished reputation is based, in part, on the paucity of recorded evidence (a sole 78) but also on the illustrious assemblage of players who passed through the group’s ranks between 1923 and 1933. Many of these musicians (Walter Page, Buster Smith, Eddie Durham, Hot Lips Page, Count Basie, Jimmy Rushing, and Lester Young among them) were virtuosos who made definitive statements on their instruments, and in the process helped to redefine the notion of what it meant to swing. As a working big band, the Blue Devils could reputedly tackle complicated ensemble passages with the kind of precision and assurance unmatched in the highly competitive dance halls of Oklahoma City, Kansas City, and other towns from the Mexican border to Omaha. That they apparently worked from head arrangements only made them all the more remarkable. Several Blue Devils went on to become key members of the Bennie Moten Orchestra, and, in what is now the stuff of legend, Motenites went on to become Basieites. Accordingly, for those whose idea of swing begins and ends with Basie, the Blue Devils may be said to sit at the center of the big band Vorstellung. In addition, their commonwealth approach to running a band—the musicians shared equally in all profits and expenses—has long endeared them to writers who champion the notion of jazz as a democratic process.

The Oklahoma City Blue Devils, the ne plus ultra of all the territory bands, still command legendary status among generations of jazz musicians, scholars, critics, and collectors. The band’s undiminished reputation is based, in part, on the paucity of recorded evidence (a sole 78) but also on the illustrious assemblage of players who passed through the group’s ranks between 1923 and 1933. Many of these musicians (Walter Page, Buster Smith, Eddie Durham, Hot Lips Page, Count Basie, Jimmy Rushing, and Lester Young among them) were virtuosos who made definitive statements on their instruments, and in the process helped to redefine the notion of what it meant to swing. As a working big band, the Blue Devils could reputedly tackle complicated ensemble passages with the kind of precision and assurance unmatched in the highly competitive dance halls of Oklahoma City, Kansas City, and other towns from the Mexican border to Omaha. That they apparently worked from head arrangements only made them all the more remarkable. Several Blue Devils went on to become key members of the Bennie Moten Orchestra, and, in what is now the stuff of legend, Motenites went on to become Basieites. Accordingly, for those whose idea of swing begins and ends with Basie, the Blue Devils may be said to sit at the center of the big band Vorstellung. In addition, their commonwealth approach to running a band—the musicians shared equally in all profits and expenses—has long endeared them to writers who champion the notion of jazz as a democratic process.

Given the dearth of research on southwestern jazz, aficionados have long awaited the publication of these books. The more problematic of the two is One O’Clock Jump: The Unforgettable History of the Oklahoma Blue Devils, by Douglas Henry Daniels, a professor of history and black studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Daniels’s narrative, interwoven with band members’ biographies, is a kind of patchwork of stories and assorted facts that occasionally cohere into a more composite picture of the Oklahoma City music world in the 1920s and 1930s. His previous jazz book, Lester Leaps In: The Life and Times of Lester “Pres” Young, demonstrated his facility with obscure sources (e.g., parish records in backwater communities like Woodville, Mississippi) and this new work is equally research-intensive. His genealogical research, which unearthed new data on Buster Smith, Hot Lips Page, and others, lends depth and authenticity to the book. He exhaustively plumbed the Oklahoma City Black Dispatch, Kansas City Call, Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, and lesser-known papers such as the Sioux City Journal, the St. Louis Argus, and the Bluefield Daily Telegraph. He also interviewed Blue Devils Buster Smith, Leonard Chadwick, Le Roy “Snake” Whyte, and Abe Bolar extensively. Through this painstaking research, Daniels traces the band in its various incarnations from their early days in the dance halls and lodges of Oklahoma City to their final, infamous gig in the mountains of West Virginia. The author provides illuminating accounts of each musician’s early history, such as singer Jimmy Rushing’s 1920s Los Angeles period and his family life in the African American Oklahoma City neighborhood known as “Deep Deuce.” Here Rushing worked in a confectionary–sandwich shop operated by his father before becoming floor manager at the Blue Devils’ Oklahoma City headquarters, Slaughter’s Hall. On this gleaming dance floor, the youthful, trimmer “James” Rushing set the tempos for the musicians and demonstrated the latest steps for the dancers.

Read more »

The minutes of the night tick down as I write this column. Soon I will have my morning reward. My column will come out on 3QD, and I will hear the thud of the Boston Globe against the front door.