by Brooks Riley

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Jeroen van Baar

In the chart-topping podcast The Rest is History, British historians Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook discuss key events from the past at great length and in sumptuous depth. I was listening to their fourth episode on the French Revolution when a detail caught my ear. Part of the reason the Revolution could occur, Tom and Dominic argued, is that a nasty opinion publique had taken hold in late-eighteenth-century Paris. Pamphlets filled with inflammatory rumors were sold by the tens of thousands and read aloud on street corners. Some of them spread fables about the alleged sexual escapades of the young queen Marie Antoinette, which eroded the authority of the monarchy and set the stage for its bloody demise.

It is all too reminiscent of public opinion today. In the recent Trump-Harris presidential debate, for instance, Trump alleged that Democrats were condoning post-birth abortions. “Her Vice-Presidential pick […] says execution after birth is OK,” Trump said. And later: The “former governor of Virginia said we put the baby aside and then we determine what we want to do with the baby.”

To those uninitiated in Republican propaganda, the comment must have sounded like yet another ridiculous falsehood made up on the fly by the former president. But as a political neuroscientist, I recognized it from five years ago. In 2019, I was a researcher at Brown University studying how the brains of political partisans color their perceptions (of an inauguration crowd, perhaps). 43 committed Democrats and Republicans watched political videos in our brain scanner. One of the videos we used was a PBS news segment on abortion, in which then-Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, a pediatrician and a Democrat, described what happens in the tragic scenario when a fetus is not viable outside the womb: resuscitation is attempted if the parents so desire. Despite numerous clarifications from Northam, this was gleefully interpreted by Republicans to mean that Democrats condone “legal infanticide”. The fact that Trump is still touting this conspiracy theory five years later speaks to its effectiveness at riling his base.

In our study, we discovered that neural processing of the PBS video was more similar between two people who had the same political orientation than across the aisle. Why? Read more »

by Nils Peterson

Galway Kinnell said all good writing has a certain quality in common, “a tenderness toward existence.” I agree and feel that one of the great maladies of our age is the communal loss of this feeling. Wendell Berry says “people exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love, and to defend what we love we need a particularizing language, for we love what we particularly know.”

Here’s the first part of a poem of mine:

Rain steady on the roof. Far shore lost. Sea quiet,

gray, introspective – like me, I think, entering

from stage left. This is what we’ve made language for,

to enter the world’s drama as player, not just reflex

towards food or away from the saber-tooth.

So now to the enemy, Word Loss.

Robert Bly in his great anthology News of the Universe recounts and comments on the dreams of Descartes as told by Karl Stern in Flight from Women:

In his third dream some terrifying things happened. A book disappeared from his hand. A book appeared at the end of the table, vanished, and appeared at the other end. And the dictionary, when he checked it, had fewer words in it than it had a few minutes before. I suspect that we are losing some of the words that inhabit the left side; our vocabulary is getting smaller. The disappearing words are probably words such as “mole,” “ocean,” “praise,” “whale,” “steeping,” “bat-ear,” “wooden tub,” “moist cave,” “seawind.”

I thought of this passage when I read this account of the new Oxford Junior Dictionary in a remarkable essay by Robert Macfarlane introducing his new book, Landmarks:

The same summer I was on Lewis [an island in the Hebrides], a new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary was published. A sharp-eyed reader noticed that there had been a culling of words concerning nature. Under pressure, Oxford University Press revealed a list of the entries it no longer felt to be relevant to a modern-day childhood. The deletions included acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell, buttercup, catkin, conker, cowslip, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, mistletoe, nectar, newt, otter, pasture, and willow. The words taking their places in the new edition included attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, bullet-point, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player, and voice-mail. As I had been entranced by the language preserved in the prose‑poem of the “Peat Glossary”, so I was dismayed by the language that had fallen (been pushed) from the dictionary. For blackberry, read Blackberry.

Macfarlane is a British naturalist whose book The Wild Places is a description of his hours and days spent in what is left of the wild. Sometimes the wild is closer than you think. Sometimes remote. It is a remarkable book that I can’t recommend too strongly. His book Landmarks is even more remarkable. It is about the loss of the language of the land that our ancestors who worked closely in it and with it had to describe it. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Meadowstream Afternoon, Maine, 2001.

Sughra Raza. Meadowstream Afternoon, Maine, 2001.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Tim Sommers

By all accounts, Alexandre Lefebvre’s new book, Liberalism as a Way of Life, is odd. For one thing, as Stephen Holmes points out, Lefebvre oscillates between saying that liberalism is so pervasive and all-encompassing that “Love it or hate it, we all swim…in liberal waters” – and emphasizing the need to evangelize and perform spiritual exercises to grasp the real meaning of deep liberalism. But as Holmes memorably puts it, “Fish do not aspire to wetness.”

By all accounts, Alexandre Lefebvre’s new book, Liberalism as a Way of Life, is odd. For one thing, as Stephen Holmes points out, Lefebvre oscillates between saying that liberalism is so pervasive and all-encompassing that “Love it or hate it, we all swim…in liberal waters” – and emphasizing the need to evangelize and perform spiritual exercises to grasp the real meaning of deep liberalism. But as Holmes memorably puts it, “Fish do not aspire to wetness.”

Here’s another bit of oddness. Lefebvre calls a spin-off article advertising the book “Rawls the Redeemer.” This is a bit like calling the Pope a secularist.

The thrust of Lefebvre’s argument seems to be this:

“Liberals too quickly adopt [a] narrow institutionalist definition [of liberalism] and assume that liberalism is an exclusively legal and political doctrine. Liberals, in other words, fail to recognize not just what liberalism has become today (a worldview and comprehensive value system) but who they are as well: living and breathing incarnations of it.”

This is not a book review, but to the extent that this adequately captures Lefebvre’s project, I am going to explain what I think is wrong with it and what the limit is on liberalism as a way of life. Let me start with what Lefebvre would no doubt describe as a narrow institutionalist definition of liberalism.

Liberalism is the view that the first principle of justice is that everyone is entitled to certain basic rights, liberties, and freedoms – such as freedom of religion, of conscience, of speech, assembly, the rule of law, and the right to participate as an equal in political and social life. People are not entitled to quantitatively “the most liberty possible” – or even “the most liberty compatible with like liberty for others.” It’s not clear what that could even mean. How do you quantify, or weigh, the freedom to swing your arms against the freedom to publish attacks on the government or the freedom to hang out with whoever you want? What people are entitled to as a matter of justice is a set of liberties adequate to allow them to develop, revise, and pursue their own understanding of the good life, the good, and justice. Roughly, liberalism is about, as Mill put it, everyone having liberties adequate to ensure their own right to pursue their own good in their own way.

Here’s a tempting, but mistaken way to justify liberal basic liberties. Call it the autonomy argument. The liberal liberties are the liberties required for people to be free and autonomous. We prioritize them because we prioritize freedom and autonomy. They reflect our political judgment that autonomy is the most important political value.

This won’t do, of course, since there is no general agreement that autonomy or freedom is the highest good. Read more »

by Ed Simon

Demonstrating the utility of a critical practice that’s sometimes obscured more than its venerable history would warrant, my 3 Quarks Daily column will be partially devoted to the practice of traditional close readings of poems, passages, dialogue, and even art. If you’re interested in seeing close readings on particular works of literature or pop culture, please email me at [email protected].

Enjambment is often an invitation to surprise. The line following a deftly deployed line break can serve as an answer to a question; it can, when done well, have an oracular quality, the feeling of a koan. Take for example Cameron Barnett’s powerful poem “Emmett Till Haunts the Library in Money, MS” published in his 2017 collection The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water. Written in the voice of Till, the fourteen-year-old Black child from Chicago lynched in Mississippi in 1955 whose murder drew attention to anti-Black violence in the United States, Barnett’s poem uses line breaks as a means to defer meaning between stanzas, and thus to generate a heightened sense of awareness. Taking as its conceit the otherworldly haunting of the Money, Mississippi library, a liminal, bardo-like space where Till’s consciousness is able to narrate even after death, the narrator’s individual thoughts are often divided across stanzas, a line break functioning as a type of psychic pause before the thought is completed. For example, in the final line of the first stanza in a three-stanza poem, Barnett writes “Mamie always preached,” completing that thought at the first line of the second stanza with “good posture, so I sit straight at least.”

Enjambment is often an invitation to surprise. The line following a deftly deployed line break can serve as an answer to a question; it can, when done well, have an oracular quality, the feeling of a koan. Take for example Cameron Barnett’s powerful poem “Emmett Till Haunts the Library in Money, MS” published in his 2017 collection The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water. Written in the voice of Till, the fourteen-year-old Black child from Chicago lynched in Mississippi in 1955 whose murder drew attention to anti-Black violence in the United States, Barnett’s poem uses line breaks as a means to defer meaning between stanzas, and thus to generate a heightened sense of awareness. Taking as its conceit the otherworldly haunting of the Money, Mississippi library, a liminal, bardo-like space where Till’s consciousness is able to narrate even after death, the narrator’s individual thoughts are often divided across stanzas, a line break functioning as a type of psychic pause before the thought is completed. For example, in the final line of the first stanza in a three-stanza poem, Barnett writes “Mamie always preached,” completing that thought at the first line of the second stanza with “good posture, so I sit straight at least.”

That divided line – “Mamie always preached” – could syntactically and grammatically be a complete sentence, and theoretically a complete thought, even while it raises the brief question in the reader of “What did Mammie always preach?” The same effect is used in the final line of the second stanza, wherein Till says “You can’t judge,” another theoretically complete thought, which is finished in the first line of the final stanza with “a book by its facts or flaps or back cover.” That line is itself interesting in that Barnett amends the cliché about books and their covers by anatomizing the structure of the book, which he then goes on to contrast with Till’s own state, for even if books are not to be judged, a “black boy/is the title and illustration staring you in the face.” The poem from The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water is able to masterfully toggle between its social and political concerns – which themselves are, remember, about a horrific crime – while imbuing the lyric with a supernatural sense. Integral to this feeling is Barnett’s treatment of those final lines in each stanza, for it gives Till’s thoughts – from the afterlife and presumably mediated through whatever gauzy filament defines the experience of haunting – a slightly delayed, almost staccato rhythm, as if in a dream state. Read more »

by Adele A.Wilby

Books on nature abound. More recently, physicist Helen Czerski’s deep knowledge of the seas functioning as an ‘ocean engine’ in Blue Machine: How the Ocean Shapes the World, elevates our understanding of the ocean and provides us with a new appreciation of its integral role in the Earth’s ecosystem. Volcanologist Tamsin Mather ‘s Adventures in Volcanoland: What Volcanoes Tell Us About the World and Ourselves is also another beguiling journey into the awesome history of the ‘geological mammoths’ that are volcanoes and their dynamics, that have changed the surface of the Earth and impacted on its environment.

Books on nature abound. More recently, physicist Helen Czerski’s deep knowledge of the seas functioning as an ‘ocean engine’ in Blue Machine: How the Ocean Shapes the World, elevates our understanding of the ocean and provides us with a new appreciation of its integral role in the Earth’s ecosystem. Volcanologist Tamsin Mather ‘s Adventures in Volcanoland: What Volcanoes Tell Us About the World and Ourselves is also another beguiling journey into the awesome history of the ‘geological mammoths’ that are volcanoes and their dynamics, that have changed the surface of the Earth and impacted on its environment.

But these books are more than the science of the specialist subject being explored: they have literary value also. The authors are to be lauded for the elegance of their prose that make the books not only fascinating and illuminating, but accessible and a real joy to read. Deeper knowledge of the planet’s ecosystems is made available to us, and they excite a sense of wonder and awe at the complexity of life on planet Earth. Cumulatively, these books highlight just how far the interrelatedness of different aspects of the natural world is. Ferris Jabr’s Becoming Earth: How Our Planet Came to Life is in that tradition. His book is a real feast for readers of books about life on Earth and for those who appreciate literary work: Jabr is not only knowledgeable, but a master of lyrical prose also.

Jabr’s book does not specialise on one aspect of the planet, such as volcanoes or the oceans. Instead, Jabr is concerned about the planet and how it came to ‘life’. In that sense he breaks with what could be considered the more conventional wisdom that posits life on the planet as being subject to its environment, and the Darwinian scientific paradigm that the changing demands of the environment dictate how life evolves and those best able to adapt will survive. Instead, Jabr focuses on what he considers the ‘underappreciated twin’ of evolution and posits a more interrelated view that ‘life changes the environment’. His book is, he says, ‘an exploration of how life has transformed the planet, a meditation on what it means to say that Earth itself is alive’.

To claim that the ‘Earth itself is alive’ truly does demand that a reader stretch the perimeters of conventional views of the Earth as an inanimate planet where the conditions for life were possible. Although the earliest iterations of an understanding of the planet as a living entity were mooted centuries ago, it is only since the 1960s when scientist and inventor James Lovelock and his association with the little known and unrecognised Dian Hitchcock, introduced the ‘Gaia hypothesis’ and later developed by American biologist Lynn Margulis, that more seriousness was given to the idea. Initially scientists subjected the ‘hypothesis’ that ‘life transforms the planet and is integral to its self-regulating process’ to rigorous criticism, but it remains, according to Jabr, the fundamental tenet in earth system science today. Read more »

A conversation between Philip Graham and Michele Morano:

Michele Morano: Philip Graham has long been one of my favorite writers to read and to teach because of his insights, humor, and ability to challenge what we think we see. A versatile author of fiction and nonfiction— whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Paris Review, Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s and elsewhere—Graham chooses subjects that explore the rippling surfaces and deep currents of domesticity at home and abroad. Each of his books illustrates Graham’s powers of perception, interpretation, and experimentation, along with his irrepressible interest in people, the more varied and unlike himself, the better. And each has contributed to the perspective of his latest project.

Michele Morano: Philip Graham has long been one of my favorite writers to read and to teach because of his insights, humor, and ability to challenge what we think we see. A versatile author of fiction and nonfiction— whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Paris Review, Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s and elsewhere—Graham chooses subjects that explore the rippling surfaces and deep currents of domesticity at home and abroad. Each of his books illustrates Graham’s powers of perception, interpretation, and experimentation, along with his irrepressible interest in people, the more varied and unlike himself, the better. And each has contributed to the perspective of his latest project.

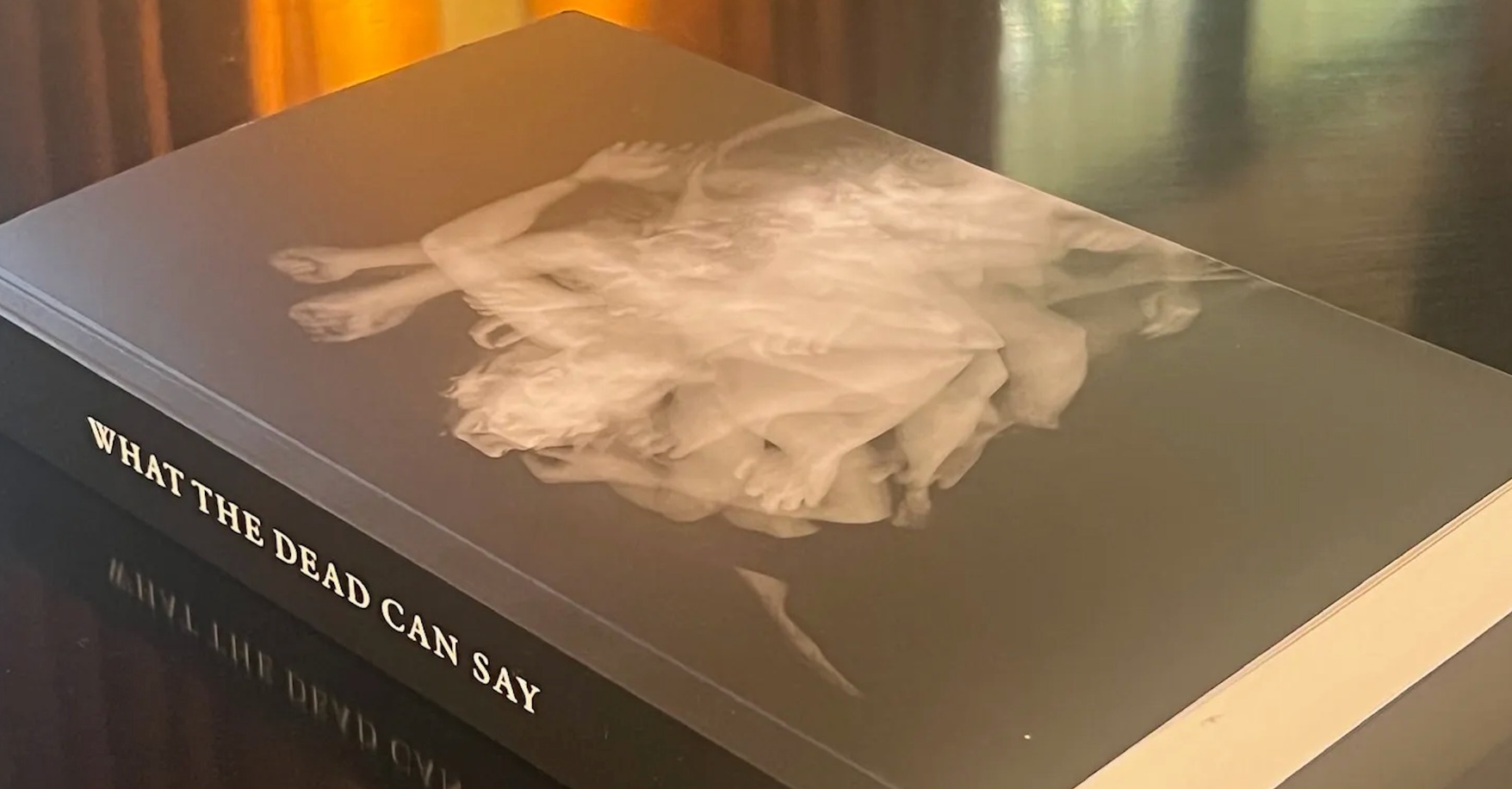

Graham’s eighth book, the novel What the Dead Can Say, is being released in serialized form in fall 2024, or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it’s continuing to be released, in a process that began in June of 2023. If that seems mysterious, imagine happening upon a FREE copy of this book, distributed in a unique way over the last year. It’s beautifully designed, printed on quality paper, and boasts an enticing cover with no author’s name, content summary, or origin story. A straight-up ghost tale, this delightful novel takes readers on a journey through life as we know it with an otherworldly narrator who, right here in our midst, cannot help but collect other ghosts’ stories as she moves through the mortal world. It’s a beautiful, fascinating—dare I say haunting?— book for which Graham chose not to follow the traditional publishing path, though his seven previous books have been published by Scribner, Random House, William Morrow, Warner Books and the University of Chicago Press.

In a recent conversation conducted via email, I asked Graham about this choice, along with many others that resulted in the production and dissemination of a terrific, uniquely curated, work of literature.

MM: Philip, would you begin by tracing for us how you came to write a ghost story? What was the inspiration for this book, and what sorts of challenges (interior or exterior) did you encounter while writing it?

Philip Graham: First, thank you, Michele, for all those kind words. I’m a great admirer of your own work, and I’m really looking forward to our conversation.

The inspiration behind What the Dead Can Say goes back thirty years, to the summer of 1993, when I gave my father a funeral in absentia in a small West African village. Read more »

by Steve Szilagyi

Herb Gobel opened Trophy Recording in downtown Boston in 1948. It was a state-of-the-art studio. Perfect for the artists Herb idolized. Big bands like Artie Shaw and Stan Kenton. Vocalists like Frank Sinatra and Peggy Lee. An era of composers, arrangers and sight-reading musicians. By the time I saw Trophy Recording in 1972, the place had gone to ruin. Cobwebs on the music stands. Cigarette burns and coffee stains on the control board. A flock of pigeons roosting in the ceiling. The proprietor himself didn’t look much better. Pale, bleary-eyed, tie dangling under the open collar of his dingy white shirt.

Herb looked like a man who didn’t know what hit him. But appearances deceive. Herb knew quite well what hit him. Rock ‘n’ Roll.

“It shouldn’t have happened,” he said, pulling a whisky bottle from under the control board. “It should have come and gone. Like all the other novelty fads” – meaning calypso, Hawaiian and “that Desi Arnez stuff.”

No union musicians. Rock ‘n’ Roll was a joke at first. The musical establishment put Be-Bop-a-Lu-La into the same category as Aba Dabba Honeymoon. Guys like Herb thought it would be absorbed into the musical mainstream. Rock ‘n’ roll songs would be arranged for horns, strings and accordions, and life would go on. No union musicians would lose their jobs.

But that didn’t happen. To survive, Herb had to push the music stands into the corner and learn how to record garage bands. It wasn’t hard. Suburban kids with new guitars weren’t very demanding. In time, Herb stopped seeing recording as a craft, and came to view it as a grift. Read more »

by Daniel Shotkin

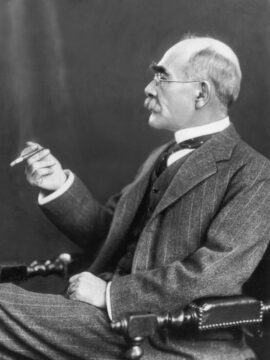

I was in 9th grade when I first heard the name Rudyard Kipling mentioned in school. My history teacher had decided to inaugurate a unit on imperialism, and Kipling’s zealous verses soon rang loudly through the classroom:

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

My teacher explained that Kipling exemplified the racist and jingoistic attitudes of late-19th-century European colonial powers. I was surprised because, to me, Kipling represented something else entirely.

I didn’t disagree with my teacher’s assessment—certainly, no one could after hearing a poem called “The White Man’s Burden.” But my confusion wasn’t unwarranted; it stemmed largely from the fact that the Kipling recited by my teacher and the Kipling I had known prior to that fateful history class seemed to be two radically different authors. Read more »

Rain on the Autobahn from Innsbruck to Munich.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Andrea Scrima

Sometimes it’s a single detail that hits home: a little girl’s pink shoe, for instance, with remnants of the delicate fabric still intact, unearthed among the hundreds of worn-down shoe soles and other objects found in the course of an archaeological excavation on the grounds of the former Liebenau camp in Graz, Austria. The site has since been paved over, covered in large part by housing settlements and a youth center, kindergarten, and sports field. The tour guides’ voices could barely be heard above the basketball game underway on a nearby court; in this vibrant residential neighborhood of Grünanger, the loud cries and laughter of everyday life suddenly seemed jarring and alien.

“Resettlement Camp V” was founded in 1940 for “Volksdeutsche” or ethnic Germans, who were relocated from the Baltic states and other parts of Europe and the Soviet Union, often involuntarily. It consisted of 190 barracks built to accommodate 5,000 inhabitants. A year later, as the war raged on, forced laborers and prisoners of war were brought here to toil under unimaginably harsh conditions in the nearby Steyr-Daimler-Puch works, which manufactured machine parts for the armaments industry. In April of 1945, the camp became a temporary stopover for Hungarian Jews on a two-hundred-mile-long death march to the Mauthausen concentration camp after the “Southeast Wall” they’d been building, Hitler’s defensive strategy of anti-tank trenches and fortifications intended to halt the advance of the Red Army along the Hungarian border, failed and they were “evacuated.” Over a period of several days, six to seven thousand exhausted and severely undernourished slave laborers arrived on foot. They had already been on the road for a week and had been given nearly nothing to eat; in Graz-Liebenau they were forced to sleep outside, on the bare ground. They received a bowl of watery soup and a single slice of bread. Those who were too sick or weak to continue were forced to lie face down in shallow trenches, where they were shot from behind, in the neck.

In May of 1947, the British occupying forces had the mass graves exhumed. A trial, verdicts, and executions followed. After that, the matter was repressed and forgotten. More than sixty years would pass before historians began investigating the site in earnest; some of the older locals still knew where the buildings once stood. A series of excavations undertaken during the construction of a power plant uncovered rubble and building foundations, personal belongings, and human remains bearing evidence of war crimes. Already a politically sensitive issue, the area became a point of contention; it was eventually declared an archaeological site requiring the oversight of specialists during any future construction projects or excavations.

The tour of the Liebenau camp was intended as a prelude to a theater performance, but the weather proved uncooperative: taking our seats on benches arranged around the open-air stage, there came a cloudburst so sudden and dramatic that it felt like a logical reaction to the devastation and destruction we had been contemplating moments before. We ran for cover; the rain was pelting down at angles that rendered our umbrellas superfluous. As I made my way home in the storm, I wondered if history is ever past, or if we’ve ever properly understood the factors that can lead to fascism and genocide. Read more »

by Carol A Westbrook

In our third year of medical school we began our clinical studies. After two full years of classroom work, it was time to apply what we learned to real patients. One can spend years in the library, reading all the books and journals that you can get your hands on, but there is no substitute for seeing a patient with disease. The stories I’m recounting here are all true, as I experienced at the University of Chicago Hospitals (then called Billings Hospital) while I was a medical student in 1977-78. I’ve changed the patients’ names, and I’ve made up some details I couldn’t recollect.

Billings hospital had a locked psychiatry ward, and it admitted patients for brief interventional stays, with a Medicare limit of two weeks. If a longer stay were required, the patient would have to be transferred to a chronic care facility. Patients could be either voluntary admissions or legally committed.

Psychiatry rotation for a third-year med student was 1 month long, of which 2 weeks were spent on the inpatient service. That was just long enough for the student to admit a patient and follow them through discharge; we each had our own individual patient. We had a four-member team (3 students and one resident) The resident took call every third night, which means they stayed overnight and answered the pager for problems on the ward or in the emergency room. We students were expected to come along. We did not carry our own pagers, but we took orders from our resident, who did carry a pager. Although call requires an overnight stay—with little sleep—it can be one of the most valuable experiences of med school, because that’s when you get to see the extreme cases, the ones you’ll never forget. Read more »

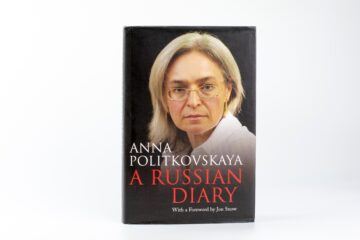

by Mark Harvey

On September 1, 2004, a middle-aged Russian journalist named Anna Politkovskaya boarded a plane in Moscow on her way to Ossetia to cover a hostage crisis in the town of Beslan. During the flight, she drank a cup of tea that almost killed her. After she drank the tea, she became disoriented, began to vomit, and ultimately lost consciousness. She was taken to a hospital in Rostov-on-Don, where doctors concluded she had been poisoned.

Politkovskaya had been reporting on the human rights abuses in Russia and Chechnya for some time and was a harsh critic of Vladimir Putin. In one of her books she had written, “If you live in Russia, you cannot help but notice that Putin’s Russia is a world of violence, lies, and injustice.”

Throughout her career, Politkovskaya received death threats and was heavily surveilled by the Russian government. But the intimidation didn’t stop her, and she wrote hundreds of articles for the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta and several books highly critical of Putin. In her 2004 book, Putin’s Russia, she bravely wrote about the corruption, human rights abuses, and oligarchy in Russia with an unflinching style.

In short, she was a daring, hardworking investigative journalist who risked her life to write about the cruel and criminal aspects of Russia. She was assassinated in the elevator of her apartment building on October 7, 2006—Vladimir Putin’s birthday. Read more »

by Bill Murray

It’s raining in Russia. Thunderheads boil up in the afternoon heat over there, behind the limestone block fortress on the other side of the river. Which is not a wide river. You can shout across it.

It’s raining in Russia. Thunderheads boil up in the afternoon heat over there, behind the limestone block fortress on the other side of the river. Which is not a wide river. You can shout across it.

Here’s how close Russia is: on Victory Day, May ninth, commemorating the Nazi defeat in World War II, Russia points big screen TVs over here toward Narva, Estonia’s easternmost city, to explain the way things really are to all these misguided Estonians.

This year Estonia put on their own concert on the town hall square. This side of the Narva River, May ninth is called Europe Day. Estonia hung a poster on its own castle wall that read “Putin is a war criminal.”

Both riverbanks are park land, well kept, landscaped, trees trimmed as if by respectful neighbors. These dueling castles mark the spot where the Teutonic Order, Swedes, Danes, Poles, Lithuanians, Slavs and local Finno-Ugrics have bumped up against each other since medieval times. This point on the map has been the tip of somebody’s sword since the 13th century.

Everybody in the train spoke Russian, Russians and Estonians both. For the confluence of Vladimir Putin’s “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” with Estonia’s triumph of independence, it’s far more Russophilic out here than I expected.

Thirty-three years after Estonian independence, that’s something to puzzle out. Part of the explanation, I think, is cultural. The other part is that it just takes time to start a new country. Read more »

Sughra Raza. On the Train to Franzensfeste. September, 2024.

Sughra Raza. On the Train to Franzensfeste. September, 2024.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Richard Farr

Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.

Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.

For years I had planned to come here, to his final resting place, and pay my genuine if heavily qualified respects. In the end the visit was almost accidental. My wife and I were walking off vast quantities of melted cheese sandwich that had accosted us in Camden Market, our destination was Hampstead Heath, and Google Maps suggested to us that the detour was slight.

The six quid you pay to get in helps the Cemetery Trust keep most of this beautiful sanctuary neat and trim, with broad main avenues and benches spaced at convenient intervals for rest and contemplation. But much of its appeal lies in a strange duality of character. Large sections are so crowded, so ivied, so root-heaved and broken that I was put in mind of Mayan temples in the Yucatan, reduced to fragments and being digested by the rainforest. Stones pristine and sundered. Inscriptions legible and illegible. Some Victorian pillars standing proud and straight but others leaning against one another like end-of-day commuters slumped shoulder to shoulder on the Northern Line.

Hopeful sentiment is engraved here over and over: Never Forgotten; Always in our Thoughts. But you look at relentless climbing nature and wonder how long any of this remembering can really last. Two generations? Three? A bit more, for the famous — but the truth is that they too will “fly forgotten as a dream,” as Isaac Watts has it. Even at George Eliot’s grave, tended lovingly by a woman with gloves and garden tools, the name itself has all but evaporated. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

How happy to have discovered the history of other species, as well as our own. How fortunate to be alive during the time when the evolutionary puzzle has been so masterfully worked out, assembling a picture so stunning in its completeness, that mere school children now know more about Darwin’s great idea than even Darwin himself knew.

And yet, how mortifying to be stuck with natural selection as “the mother of beauty,” to crib from the poet Wallace Stevens. (“Death is the mother of beauty; hence from her,/ Alone, shall come fulfillment to our dreams/ And our desires.”) Accepting this brute fact of life is a tall order, and I still recoil whenever I contemplate what Darwin called the “sufferings of millions of the lower animals throughout almost endless time.”

The central tenet of life is directionless, indifferent, insensate, implacable natural selection. And yet . . . here we are.

*

We have — or had — five cats. Four are sibs, seven years old now, Girly, Rocky, Pinky, and Scooter. They showed up, mere kittens clustered near their scrawny mother, behind our barn, as my husband Don was recovering from a stroke that occurred the year before. The fifth, Maggie, showed up just last summer, barefoot and pregnant, on our back doorstep. She hated and still hates the others. She eventually gave birth to four kittens of her own, which we judiciously distributed, but we still have to keep her separate from the other cats.

While returning from teaching one day earlier this month, I saw Rocky, our black, tuxedo male, vaulting across the road, his skinny ass stretched out like a black snake as he made it safely to the other side.

“I just saw Rocky sprinting across the road in front of me,” I said to Don. “Prepare yourself. We’re going to lose that cat.” I sometimes actually believe that articulating a fear helps to diminish it . . . Read more »

‘tis the little things, for sure

‘tis a little thing the way the toast pops up

in the morning, ‘tis magic that took

billions of years to enter the picture

to brown two sides of bread at once

in the kitchen of a little castle

‘tis the little things, for sure

‘tis a little thing that we met one day

among the multitudes who dance upon

the surface of a sphere who ever chase

the big thing of why? the impossible thing

’tis the little thing of those last four lines above,

among all the unknown possibilities,

of all the little things, ‘tis the one

that changed my heart

‘tis the little things, for sure

Jim Culleny, 8/1/24

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.