by Tim Sommers

Judges judge. The way to tell that someone is a judge, as opposed to a legislator, is to examine whether the judge judges actual ongoing controversies between particular people who have incurred, or will incur, specific harms – or not. In that sense, the difference between legislating and judging is locus standi – or “standing.” Article III of the U.S. Constitution extends to the judicial branch of the US government only the power to decide “cases and controversies.” To seek a judicial remedy, one must demonstrate a sufficient connection to a harm to them personally that is a result of a law, or action, that is the subject of their case.

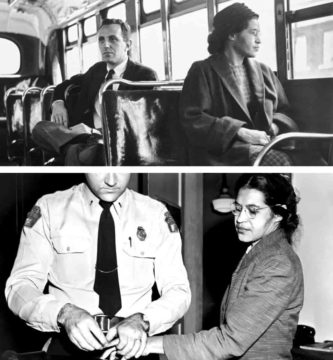

Civil Rights Activists were forced to commit civil disobedience, to openly break laws, and be punished for doing so, because “law testing” is (or, rather, was) not allowed. To have standing in cases where people of color were denied the right to be in certain spaces, someone of color had to go into and physically occupy those spaces, then face the legal, and often actual physical, peril that resulted. In other words, Civil Rights Activists were not allowed to challenge the Constitutionality of laws in an American court without standing. And they couldn’t get standing without breaking the (relevant) law.

But that’s all done with now. Now, you are free to pursue a case all the way up to the Supreme Court on the theory that hypothetically someone might one day break that law or merely disagree with it on policy or political grounds. This is what I mean by the death of standing. I’ll just give two examples from the last session of the Supreme Court. But there are other recent cases suggesting standing is no longer a thing.

In 303 Creative v Elenis, Lorie Smith was planning to, in the future sometime, expand her graphic design business to include a business (that she was currently not involved in) which would create websites for weddings, if someone happened to ask her to do so later on. In Colorado, where she was located, there’s a public accommodation law that forbids business, in the ordinary course of doing business, from declining to service customers who identify as homosexual or trans. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 already forbids discrimination based on national origin, sex, religion, color, or race, of course, so you might think that sex discrimination already covered homosexuality and people who identify as non-cis gendered. There’s certainly precedent to treat discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender-identification as sex discrimination (Seem, my article on Bostock v Clayton.) But the state of Colorado went the extra mile to explicitly treat people who identify as gay or trans as a protected class. Since Smith planned to violate that statue, and discriminate against gay and trans people, at some time in the future, she sought explicit permission from the courts to do so – which they gave her. The SCOTUS majority in their decision characterized her suit like this, “To clarify her rights, Ms. Smith filed a lawsuit seeking an injunction to prevent the State from forcing her to create websites celebrating marriages that defy her belief that marriage should be reserved to unions between one man and one woman.”

Again, she was not currently being “forced” to do anything. No one had asked her to do any kind of wedding website. But the jaw-dropping bit is the explicit description of her aim as “To clarify her rights…” It’s basically an open admission that she doesn’t have, or have to have, standing.

Although from a legal perspective this next bit is inconsequential, from a human perspective it makes things even worse. As I said, in court filings, Smith had admitted previously that no one had asked her to make a website for a gay marriage. Then, by a remarkable coincidence, she received just such a request the night before the first day of the trial. In a less remarkable denouement, after the SCOTUS decision the person she had identified as having asked for the website denied making the request, denied knowing the plaintiff, and said that, while he supports LGBTQ+ rights, he was straight and married to a woman.

Among other things, this case showed that SCOTUS is prepared to allow people seeking “to clarify their rights” to file cases even where they lack standing, presumably, so SCOTUS (as opposed to Colorado or Congress) can decide what the law should be.

Consider also Biden v Nebraska (which in addition to being the name of a SCOTUS case is a pretty apt description of the political moment). The Biden administration claimed that under Title IV of the Higher Education act of 1965 Title IV and the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act of 2003 (HEROES Act) they had the ability to forgive billions of dollars in student loans without further Congressional authorization. The act read in part that the Secretary of Education “may waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs…deem[ed] necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency.” The court decided that “waive and modify” did not mean waive or modify, or at least it meant don’t waive or modify in any way which is inconsistent with the current policy positions of the Republican party. (It’s also true that the case was allowed to skip the normal procedures to bring a suit to the court and the law was decided by SCOTUS before the facts were decided. But I want to focus on standing.)

The suit was brought by a number of state Attorney Generals who wanted to prevent the loan forgiveness program. They knew that they needed particularized harms to specific persons, or entities, to gain standing, but it was hard to say who was being harmed by free money. Also, it’s a well-established bit of common-law that the government misusing your tax money doesn’t give you standing (and must be dealt with through ordinary legislative processes), neither does saying that your State is affected by some Federal action that also applies equally to all states give you standing (for basically the same reason, it is a matter for ordinary legislative processes). So, here’s what the AGs came up with. They decided to sue on behalf of the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority (MOHELA), one of the largest holders and servicers of student loans in the United States.

They argued that MOHELA was the specific entity that had suffered an identifiable harm in this case. Only they didn’t and don’t work for MOHELA or own MOHLA, neither were they hired nor retained by MOHELA for legal services, nor was MOHELA suing or in anyway involved in the suit in which they were being named. Which is crazy enough, but then there is this. The final result of Biden’s program would have been to increase MOHELA’s bottom line. How is making more money a harm?

Deciding what the law will be without considering any particular case, or the plight of any specific individual, is legislating. When the law is, not applied, but is made in this way, by unelected judges with life-time appointments to positions explicitly without any code of ethics, any oversight, or any chance of further appeal, this is not democratic.

Hence, the death of standing is the death of democracy.