by Rafaël Newman

I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Which is a wildly non-specific thing to say, since the province of Ontario, though only the second largest of Canada’s constituent divisions, boasts a surface area greater than those of Germany and Ukraine combined. But while I would normally designate as my destination the city in Ontario in which I mean to stay during my annual visit to my home and native land—as for instance Toronto, the provincial capital, where I went to high school and university; or Kingston, once Canada’s Scottish-Gothic capital, where my brother has settled with his family—the particular reason for this year’s sojourn, which began with a brief visit to relatives in Montreal, was my niece’s wedding, on August 12, celebrated at her fiancé’s family home in Frankford, with guests put up in the towns surrounding that hamlet on the River Trent, in Hastings County, the second largest of Ontario’s 22 “upper-tier” administrative divisions. Which all feels to me quite uncannily foreign, not to say unutterably vague. Hence simply: I’ve been visiting Ontario this month.

I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Which is a wildly non-specific thing to say, since the province of Ontario, though only the second largest of Canada’s constituent divisions, boasts a surface area greater than those of Germany and Ukraine combined. But while I would normally designate as my destination the city in Ontario in which I mean to stay during my annual visit to my home and native land—as for instance Toronto, the provincial capital, where I went to high school and university; or Kingston, once Canada’s Scottish-Gothic capital, where my brother has settled with his family—the particular reason for this year’s sojourn, which began with a brief visit to relatives in Montreal, was my niece’s wedding, on August 12, celebrated at her fiancé’s family home in Frankford, with guests put up in the towns surrounding that hamlet on the River Trent, in Hastings County, the second largest of Ontario’s 22 “upper-tier” administrative divisions. Which all feels to me quite uncannily foreign, not to say unutterably vague. Hence simply: I’ve been visiting Ontario this month.

Ontario at large, small-town Ontario, Ontario beyond “the six,” Toronto without its vast suburbs, so-called for its prestigious area code, feels foreign to me because it first came to my attention, when I was around eight years old, as a vast, unknowable hinterland, the beginning of Canada proper, somewhere to the west of the province of Quebec, whence my entire immediate family hales—more to the point, to the west of the city of Montreal, where I was born, and which seemed to me, in my early years, the only real place in the country: Montreal, with its distinctive rows of duplexes, its outdoor staircases, its smoked meat sandwiches, its bagels, its maple-sugar holidays and its antiquated French dialect. “Ontario,” generally, had no culture, no flavor, no flair; it was too Anglo, too American, too goyish.

But this very same Ontario is also uncanny—known and yet unknown—because it was renowned (not to say notorious) during my youth as the site of certain signal family events, or episodes: for instance, the accidental death of Great-Uncle Hymie, my Aunt Mildred’s husband, while attempting to reverse down the on-ramp of the 401 outside Cornwall, Ont., just west of the Quebec provincial line, and his son’s tearful gratitude to my grandfather for that latter’s company on the trip to identify his father’s remains; or the time spent in Brockville, 100 km farther along the St Lawrence in what had once been Upper Canada, by my grandmother Eva Kornpointner, née Strassner, of Switzerland, when she first arrived in Canada in the 1930s, a very young woman, to take up a position as au pair for a well-to-do Canadian family, before she met Franz, the Bavarian immigrant who was to become my grandfather.

The young couple settled, naturally, in Montreal, at the time Canada’s premiere city and commercial capital. Toronto, a century-and-a-half younger and with far less “European” élan than its downstream counterpart, was, in a sense, barely on the map. In the intervening decades, the capital of Ontario has surpassed Montreal as Canada’s largest city and developed its own plausibly cosmopolitan reputation; and it is the place I am most likely to name as my hometown these days. But I still have only the vaguest idea of the enormous province around (and mostly north of) it, composed of small towns, mines, and farmland; and so, to prepare myself for venturing into familiar but unknown territory, I decided I would turn to a canonical source.

In Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912), a collection of twelve interconnected short stories, Stephen Leacock evokes a vision of provincial Ontario life that is at once familiar and estranged: just the right mixture to suit my purpose. Leacock’s own biography nicely sums up the main strands in Canadian colonial life. Born in a village in the south of England, at the age of six he emigrated with his family to rural Ontario, studied at Upper Canada College and University College in Toronto, went on to graduate studies with Thorstein Veblen at the University of Chicago, and spent his academic career as chair of the Department of Economic and Political Science at McGill University in Montreal. This combination—European immigration, rural and urban experience in the colonies, Canadian and American education, and a connection to what was to become the center of French culture in Canada—is not only emblematic of the eastern Canadian colonial experience generally; it also mirrors my own experience. For I may not have attended the same Toronto high school Leacock had, almost a century earlier—I went to the less elitist, though equally excellent, Jarvis Collegiate Institute, or JCI—but I did go on to be a member of University College at the University of Toronto, and to do graduate studies in the United States; and I am also the product of European immigration with a vital connection to francophone Canada.

In Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912), a collection of twelve interconnected short stories, Stephen Leacock evokes a vision of provincial Ontario life that is at once familiar and estranged: just the right mixture to suit my purpose. Leacock’s own biography nicely sums up the main strands in Canadian colonial life. Born in a village in the south of England, at the age of six he emigrated with his family to rural Ontario, studied at Upper Canada College and University College in Toronto, went on to graduate studies with Thorstein Veblen at the University of Chicago, and spent his academic career as chair of the Department of Economic and Political Science at McGill University in Montreal. This combination—European immigration, rural and urban experience in the colonies, Canadian and American education, and a connection to what was to become the center of French culture in Canada—is not only emblematic of the eastern Canadian colonial experience generally; it also mirrors my own experience. For I may not have attended the same Toronto high school Leacock had, almost a century earlier—I went to the less elitist, though equally excellent, Jarvis Collegiate Institute, or JCI—but I did go on to be a member of University College at the University of Toronto, and to do graduate studies in the United States; and I am also the product of European immigration with a vital connection to francophone Canada.

That’s the familiar part; what estranges me from Leacock is his biographical Britishness—the fact of his birth in Swanmore, Hants, in the UK, one of the few regions of the Old World, it seems, from which I cannot claim ancestry—as well as his British imperialist politics, his lifelong adherence to Canada’s version of the Tory party, and his chauvinism regarding non-British immigration to his adopted homeland, as well as a tiresome superiority complex towards the indigenous peoples of Canada. And of course, as celebrated in his Sunshine Sketches, Leacock also had an important connection to that same rural Ontario in which I have been traveling, and in which I feel strangely (not) at home.

Leacock’s family had initially settled on a farm outside Toronto, and the fictional Mariposa of his stories is based on the town of Orillia, in Toronto’s “cottage country,” the area north of the city in which small lakes provide idyllic settings for country homes. Now, my family had a summer cottage as well, on a lake, built by my grandfather Franz; but our Lac Noir was located outside of Montreal, and thus within the orbit of the cosmopolitan French and assorted non-British European culture of that city, a Catholic and Jewish id to Ontario’s Protestant superego.

As it happens, at JCI in 1980 we had been given one of Leacock’s stories to read, in Mr Barker’s Grade 13 English class. “The Marine Excursion of the Knights of Pythias,” a mock tragic account of a mishap on the imaginary Lake Wissanotti, was my first exposure to Mariposa, Leacock’s version of his contemporary Proust’s Combray, and the ancestor of Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon, a place of wistful nostalgia for a simpler time. “Mariposa is not a real town,” Leacock writes in the preface to his book. “On the contrary, it is about seventy or eighty of them. You may find them all the way from Lake Superior to the sea, with the same square streets and the same maple trees and the same churches and hotels.” Leacock’s Mariposa is a distillation of small-town Ontario, its quintessence and its sublation, as well as an ironic admission of failure in the face of “trying to do anything so ridiculously easy as writing about a real place and real people.” Mariposa is a celebration of “a land of hope and sunshine where little towns spread their square streets and their trim maple trees beside placid lakes almost within the echo of the primeval forest… If it fails in its portrayal of the scenes and the country that it depicts the fault lies rather with an art that is deficient than in an affection that is wanting.” In his effort to represent truth by way of fiction, and thus to exalt the landscape of his own past, Leacock is aware that his composite portrait always runs the risk of falling short of the singularity of its subject.

But Mariposa is also kin to Seldwyla, Gottfried Keller’s stand-in for 19th-century Zurich, as well as to Chelm, the setting for pre-Shoah Jewish jokes: sites of small-minded bigotry and legendary foolishness. In Leacock’s case, the sting is taken out of the satire by his eccentric use of second-person narration, as if he were recounting anecdotes to a friend at the bar. (The contemporary comedy series Letterkenny, about a similarly fictional Ontario small town, uses the same conceit, with characters breaking the fourth wall to address viewers directly in a brief prologue to each episode, before re-emerging as figures in a scurrilous sketch of small-town life.) Leacock’s townsfolk, who appear and reappear in a variety of constellations and with varying degrees of foregrounding throughout the collection, are figures emblematic of provincial life among colonial settlers at the turn of the 20th century: would-be speculators and scofflaw entrepreneurs; amateur archeologists and local historians; political operatives and frank opportunists; blowhards, bluffers, diehards and turncoats. (The clockwork alternation of Liberal and Conservative federal governments, whose election regularly reveals that everyone in town has secretly been a Grit or a Tory all along, or vice versa, depending on the outcome, continues in Canada to this day.)

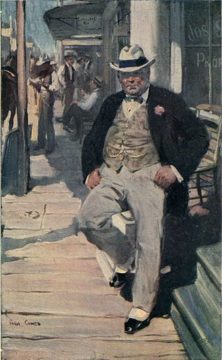

There is Mr. Smith, the chancer from “up north” turned hotelier, flouting Ontario’s puritanical restrictions on alcohol consumption with an eye to cementing his influence over the local pharisees; there is the barber, Jefferson Thorpe, whose windfall on the stock market, due more to simple mulishness than to acumen, makes him (briefly) a financial wizard in the eyes of his neighbors; there is Rural Dean Drone, incumbent of the Church of England Church and amateur Hellenist, who defends himself against Dr. Gallagher’s deadening displays of “Indian relics” with off-puttingly incomprehensible recitations of Theocritus; and there are Peter Pupkin and Zena Pepperleigh, scions of two differently prestigious families, whose “Fore-ordained Attachment” runs the course of three consecutive sketches, and whose cross-caste romance (Zena is merely the local judge’s daughter, while Peter, although currently working as a lowly bank teller, is from real wealth in the city) reveals the system of distinctions at work even among the very top echelons of this society.

Peter Pupkin also plays a central role in the collection’s uncanniest story, in which I perceive a certain essential truth of Canadian colonial history, and of my own experience of it. When he is awakened one night, in his lodgings above the bank, by what he believes is a robbery in progress, but is in fact merely Gillis the night watchman making his rounds, Pupkin creeps down into the bank vault to intervene—with the result that both he and Gillis, each armed with a pistol and each believing the other to be the burglar, suffer superficial gunshot wounds. The “Mariposa Bank Mystery” goes unsolved, but Pupkin is “exalted into the class of Napoleon Bonaparte and John Maynard and the Charge of the Light Brigade,” awarded a raise, and given Zena’s hand in marriage.

These fairy-tale trappings are enhanced in the sketch’s close, in Leacock’s characteristic second person: “So Pupkin and Zena were in due course of time married, and went to live in one of the enchanted houses on the hillside in the newer part of the town, where you may find them to this day.” The legendary quality of the romance suggests that there is something archetypal about the episode; and indeed, what I believe takes place in the vault of the Mariposa Bank is an ironized replay of a pivotal encounter between the two main groups of European settlers in Canada.

In September 1759, during the Seven Years’ War (AKA the French and Indian War), the French and British forces met in battle on the Plains of Abraham, outside Quebec City in what had been until that point New France. The conflict was decided by the British, who would go on to add New France, as Lower Canada, to their existing possessions up the Saint Lawrence in Upper Canada.

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham is, however, also renowned for the special pathos of the fact that its two enemy commanders, the Generals Wolfe, of the British, and Montcalm, of the French, both died of the wounds they had received during the brief engagement. And the combat has been notorious among separatist Quebecois as the moment at which their claim to mastery of that corner of the New World was challenged, and rebuked: the grounds of a sacred defeat, a wound cherished and relished, the site of a ressentiment-filled hope for a national rebirth akin to the Serbs’ attachment to Kosovo Field, where the Serbian Prince Lazar met the Ottoman Sultan Murad in 1389. (There too, both enemy commanders fell in battle, although the outcome was far less decisive than on the Plains of Abraham.)

Memory of the French defeat at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, as of the two-and-a-half centuries of French colonial history that preceded it, and the two centuries of subaltern existence that followed it, acquired especial significance in the nineteen-seventies, when the francophone majority population in the province of Quebec, under the stewardship of the Parti Québécois, wrested political power from the anglophone minority and attempted, in a series of ultimately unsuccessful referenda, to secede from Canada. In 1978, Quebec’s provincial motto, the anodyne La belle province (“The beautiful province”) was replaced with the more rhetorically charged Je me souviens (“I remember”), inscribed in topiary into the slopes around Quebec City, near the site of the battle, and prominent in the changing of the guard ceremony there. What preserves the “nation” of Quebec, formerly known as New France, in its belief in its own uniqueness in North America is thus a memory of usurpation, of having its sovereignty contested, and subordinated to another.

Memory of the French defeat at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, as of the two-and-a-half centuries of French colonial history that preceded it, and the two centuries of subaltern existence that followed it, acquired especial significance in the nineteen-seventies, when the francophone majority population in the province of Quebec, under the stewardship of the Parti Québécois, wrested political power from the anglophone minority and attempted, in a series of ultimately unsuccessful referenda, to secede from Canada. In 1978, Quebec’s provincial motto, the anodyne La belle province (“The beautiful province”) was replaced with the more rhetorically charged Je me souviens (“I remember”), inscribed in topiary into the slopes around Quebec City, near the site of the battle, and prominent in the changing of the guard ceremony there. What preserves the “nation” of Quebec, formerly known as New France, in its belief in its own uniqueness in North America is thus a memory of usurpation, of having its sovereignty contested, and subordinated to another.

It is this memory that is lampooned, in Leacock’s account of a romance sealed in the vault of a bank, where two claimants to the space confront one another, each believing the other to be the interloper. Because of course, in what was to become Canada in the early modern period, neither the French nor the British had an ancient, “autochthonous” claim to the land, which both European forces were in the process of taking from its indigenous inhabitants. There was thus no more “natural” or historical reason for the French to occupy New France, than for the British to seize it and rename it Lower Canada.

In The Prague Cemetery, Umberto Eco evolves a perverse theory of the emotions and assigns it to his antisemitic protagonist:

You always want someone to hate in order to feel justified in your own misery. Hatred is the true primordial passion. It is love that’s abnormal. That is why Christ was killed: he spoke against nature. You don’t love someone for your whole life—that impossible hope is the source of adultery, matricide, betrayal of friends … But you can hate someone for your whole life—provided he’s always there to keep your hatred alive. Hatred warms the heart.

In remarks at a public lecture, Eco sums up this “transvaluation of all values” in an ironic formulation: love is possessive and solipsistic, but hatred is generous and unifying, because while two people in love exclude the rest of the world, hatred has the power to bind an entire people together in their animus towards another people.

Leacock’s staging of the union of Peter Pupkin and Zena Pepperleigh, with its roots in an act of mutual violence between pretenders to mastery of a subterranean store of value, prefigures this reversal, and serves as an uncanny allegory of the history of Canada: a place where a contest between equally unjustified colonizers of a valuable space, which actually belongs to another, repressed people, provides the ground for individual acts of attachment. Now, moving from Quebec to Ontario on my holiday visit this past week, I have recapitulated a historical journey: my own, when my family left Montreal for parts west in the early nineteen-seventies, and the greater colonial episode that grounded it, when mastery of the entire space moved from the French to the British, and gave rise to the mutual animus that has united the two settler peoples ever since, at the expense of the indigenous peoples their occupations have variously disadvantaged. And why did I make this return journey, across a terrain of conflict between two peoples, subtended by the subjugation of a third, all of whom now live together in tension? Why, to help celebrate a wedding!