by Derek Neal

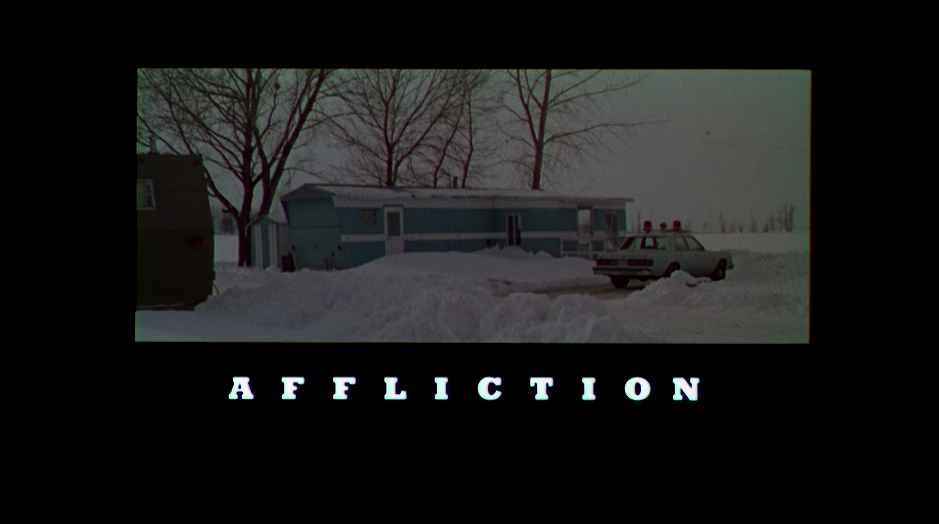

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

This is the story of my older brother’s strange criminal behavior and disappearance. We who loved him no longer speak of Wade. It’s as if he never existed. By telling his story like this, by breaking the silence about him, I tell my own story as well. Everything of importance, that is, everything that gives rise to the telling of this story occurred during a single deer hunting season in a small town in upstate New Hampshire where Wade was raised, and so was I. One night, something changed and my relation to Wade’s story was different from what it had been since childhood. I marked this change by Wade’s tone of voice during a phone call two nights after Halloween. Something I had not heard before. Let us imagine that around eight o’clock on Halloween Eve…

Then the narrator’s voice disappears, and we are in the car with Wade, played by Nick Nolte, and his daughter. We are in the story, we are ready to be swept away, or in the case of this movie, submerged into the depths, but we have been prepared in such a way—starting from outside the story, outside the narrative—that we are aware of the artificiality of what we are seeing. Affliction tells us that it is a movie. The small images, which look like postcards, are presented to us as miniature models of different sets. The farmhouse becomes “THE HOUSE.” The main street becomes “MAIN STREET.” While they will take on specific characteristics within the movie, we know from the prologue that they are eternal, and we will be reminded of this at the end as well.

The voiceover achieves a similar effect. The narrator, played by Willem Defoe, removes tension and drama from the plot by spoiling the ending: Wade becomes a criminal and disappears. He does not even attempt to convince us that the story is real, that it actually happened, because he says, “Let us imagine.” Is this not bad storytelling? It may be appropriate for a children’s story, a fairy tale, but for a mature film like Affliction, a film dealing with murder, paranoia, and male violence? Shouldn’t a story like this try to convince its audience that it’s real, by building up a wealth of detail and creating realistic, lifelike characters? Perhaps a certain type of story, but not this one. Read more »

Egypt

Egypt Germany

Germany

In her provocative, genre-defying book,

In her provocative, genre-defying book,

There is a

There is a  Drug overdose deaths have more than doubled in America in the past 10 years, mainly due to the appearance of Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. These drugs combine incredible ease of manufacture with potency in tiny amounts and dangerousness (the tiniest miscalculation in dosage makes them deadly).

Drug overdose deaths have more than doubled in America in the past 10 years, mainly due to the appearance of Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. These drugs combine incredible ease of manufacture with potency in tiny amounts and dangerousness (the tiniest miscalculation in dosage makes them deadly).

Death has stalked me of late, claiming those whom I was once close to, or who remained closest to those who are closest to me.

Death has stalked me of late, claiming those whom I was once close to, or who remained closest to those who are closest to me.