by Gary Borjesson

Become who you are, having learned what that is. -Pindar

Become who you are. —Nietzsche

I want to be authentic and so probably do you. It’s a virtue fostered by philosophic and therapeutic inquiries. In popular culture, “authenticity” is broadly used to mean being true to oneself—often with an emphasis on not caring what others think. Thus its critics see authenticity as encouraging a culture of narcissism, since it appears to focus on self-actualization at the expense of other ideals, including healthy relationships and communities, and the social values such as honesty, fairness, and justice that support these. Here I offer a philosophically informed definition of authenticity, drawing attention to why, despite popular usage, it is a prosocial, ethical ideal.

Authenticity may indeed be the virtue of being true to oneself, but what does that mean? To some it means being the creator of one’s own truth and value, and living solely according to these. Imagine a bright, rebellious teenager who’s read a little Nietzsche. They decide that the first step to becoming authentic is to take up their philosophic hammer and use it to smash all external claims and constraints —those truths, values, and beliefs that come from family, religion, community, customs, traditions, even from nature herself. This apparently asocial or even antisocial tendency is partly how authenticity gets associated with nihilism and moral decline, rather than being the virtue I suggest it is.

As many have pointed out, including Allan Bloom in Closing of the American Mind, this narcissistic-fantasy version of authenticity stems from a philosophy of “cheerful nihilism,” a memorable phrase borrowed from Donald Barthelme. It’s cheerful because it’s about freedom from responsibility, rather than being freedom with responsibility. The roots of this nihilism can be traced to reductive materialism in the sciences and postmodernism in the humanities—ideologies that find fertile ground in individualistic capitalist societies, where everyone competes to get the most they can. These days one can see this “ethic” prominently displayed among politicians and tech billionaires, but this is not authenticity. (Philosopher Charles Taylor’s short book The Ethics of Authenticity offers a good account of the history and future of authenticity.)

The ethical definition of authenticity includes the observable fact that we own our lives and truth in the world. Specifically, becoming authentic concerns taking our place in the world—even if it’s the place of a rebel. For where else but in a world do we learn who we are, and actualize ourselves? Our very power of living, thinking, and speaking owes its development to others. Thus, a free spirit or rebel or Libertarian may imagine they are powered by their truth alone. But without a world, there’s nothing to rebel against, and nothing from which to liberate the spirit. Read more »

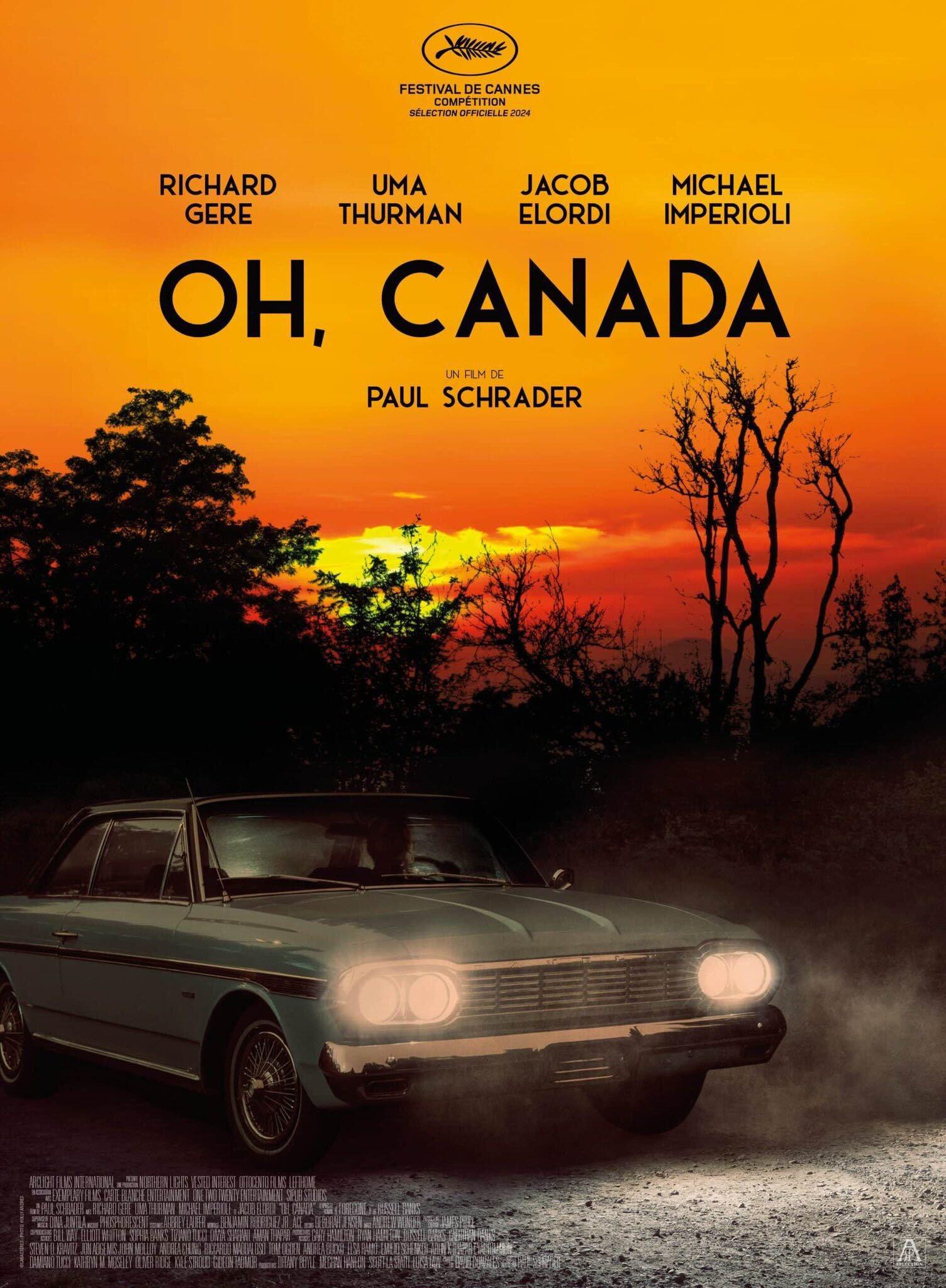

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks. The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

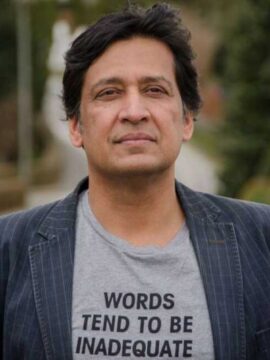

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels