by Marie Snyder

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Meditation is not about escaping the world but sharpening our awareness of it. Addiction comes from the Latin dicere, related to the root of the word dictator. It’s like having an internal dictator usurping our agency. And Buddhist mindfulness meditation can help to notice that voice and then turn the volume down on it so we can get our lives back.

In many ways the Buddhist perception is closer to Stoicism than to Freudian tactics, but don’t toss the baby out with the bathwater. Many people benefit from the psychoanalytical method of finding themselves before they can work on losing themselves. This is particularly true with traumatic experiences that might need to be worked through enough before allowing the mind to wander into dark recesses unrestrained.

Some research has found Buddhism to be as effective at treating addiction as typical methods, which is never anywhere near 100% because addiction is brutally difficult to overcome. One study of 500 opioid addicts had half use a detox program with counselling and the other half study in a Buddhist monastery with a focus on meditation and virtuous living. The abstinence rates were the same. The monastery used meditation to help clients (clients?) recognize the path they’re on, then contemplating virtuous living to find their way back to a preferred path that’s less frazzled and chaotic. Before researching the role of Buddhism in addiction treatment, it hadn’t occurred to me that mindfulness meditation had anything to do with the Buddhist Noble Eightfold Path of virtuous living. All these years of dipping into meditation here and there, I had just been arguing with myself to stop my thoughts from racing, craving the perfection of enlightenment, and missing the most important aspects in the process. Like Stoicism, Buddhism has us check our thoughts and actions to intentionally get on the right path.

The Hungry Ghost

Where the Freudian view has us look to our traumatic childhood for a clue to our current issues, Buddhism looks to karma. That’s not just synonymous with comeuppance as it’s often used, but closer to the epistemological sense of determinism. What we’re experiencing now isn’t just due to an issue with a caregiver, but also everything else that’s happened that’s brought us to this point in time. One benefit of this perspective is that it eliminates blame. It’s not the fault of a parent or poverty or laziness or any one thing, but of everything interacting altogether.

The Buddhist view sees us stuck in the realm of the Preta, one of the six realms of samsaric existence in a Wheel of Becoming. Preta is the hungry ghost that is insatiable, with a distended belly that can’t be soothed. Instead of looking at our craving as a product of a failure along the way, Buddhism looks at craving and aversion themselves as the natural cause of our worldly suffering. There is a shame engulfing addiction that suggests we’re defective, which prevents a connective realization that we’re all craving and grasping at things, but it’s this very nature of longing that’s the real problem, and it can be quieted.

The Buddhist view sees us stuck in the realm of the Preta, one of the six realms of samsaric existence in a Wheel of Becoming. Preta is the hungry ghost that is insatiable, with a distended belly that can’t be soothed. Instead of looking at our craving as a product of a failure along the way, Buddhism looks at craving and aversion themselves as the natural cause of our worldly suffering. There is a shame engulfing addiction that suggests we’re defective, which prevents a connective realization that we’re all craving and grasping at things, but it’s this very nature of longing that’s the real problem, and it can be quieted.

We’ve tried to call addiction a disease to brush off the shame attached, comparing it to having a broken leg or tumour, but it didn’t quite take. It’s still spoken of in hushed tones and seen as brought on by debaucherous living, inept parenting, or a faulty society. But the Buddhist perspective suggests there’s nothing wrong with us; we just haven’t had enough practice or experience with non-craving behaviour. How can we fail at something we’ve never tried? It’s like playing the piano for the first time. We’ll struggle with it and sound horrible, through no fault of our own. It just takes practice to get better. A perspective of the problem as inexperience makes failure less daunting, which makes it easier to be open to try.

“When you plant lettuce, if it does not grow well, you don’t blame the lettuce. . . . Blaming has no positive effect at all, nor does trying to persuade using reason and argument. That is my experience. No blame, no reasoning, no argument, just understanding.” – Thich Nhat Hanh

Furthermore, an addiction is like a useful set of armour that helps us through the world, but eventually it gets too heavy and cumbersome until we’re finally ready to start shedding it. Addictions offer a temporary illusion of protection from suffering that then becomes a cause of suffering. Specifically, addictions offer protection from the present moment. We’re fighting just being. We get a little bored or aggravated or sad, and we reach for a drink to soften the hard edges or start to scroll through social media to distract ourselves – anything to take us away from being right here right now. But if we can sit with the present and tolerate our discomfort with it, then what we might consider negative emotional states can be opportunities: boredom can become creativity, aggravation turns to innovation, and sadness can bring us to the awareness of the precious beauty in the world.

Slivers of Quiet

Like the 12 steps, Buddhism has us accept where we our on our path, but that’s not about accepting our lot in life and throwing up our hands in resignation. We accept that we’re here, and then take aim at a getting on a different path that reminds us to seek to make sure each thought and action we pursue is virtuous. It gives us a template to make a path instead of being compelled down one. But there are no shortcuts. It’s an effort, and the difficulty of the effort is part of the point. Meditation is uncomfortable. For someone like me, impatient and busy and ready to get on to the next thing, sitting for twenty minutes is a feat of strength! That discomfort itself, practiced over and over, is how we can practice tolerating those moments that we typically fight to avoid. The key is developing a discipline. If I can sit for 20 minutes without doing anything, then I can make it through 20 minutes of doing anything without needing something else to help me escape myself in this present moment. Maybe I can even read an entire chapter of a book again without checking Twitter! Most of the time when we check social media, it’s not to seek information or connection, but because we’re avoiding this moment. The algorithms take advantage of our nature. Meditation just keeps bringing us back to sitting with it, tolerating nothing so our mind can be at rest.

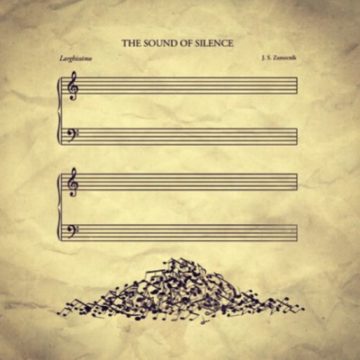

But there’s more! We all try to escape this uncomfortable itchiness with ourselves. In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud writes off meditation as escapism similar to drug use, and he counters that good escapism is immersion in work or creative pursuits. But meditation isn’t just another way to avoid or become numb to the world. Instead it develops the capacity of awareness of the moments of quiet that already exist between our thoughts. They’re there already; they just need to be noticed. These moments of nothing are vital. It helped me to understand like to a piece of music has rests that provides moments of quiet that are indispensable to the music, or similar to how a painting has areas of restraint, areas with nothing happening that are necessary for us to better see what is happening. Without the moments of nothing, music, art, and our minds are just chaos. We meditate to find that nothing. Once we can find these gaps between our thoughts, we can work to sustain them a little longer each time. It’s not about stopping our thoughts or fighting to get them to settle down, but just noticing those slivers of peace between them.

But there’s more! We all try to escape this uncomfortable itchiness with ourselves. In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud writes off meditation as escapism similar to drug use, and he counters that good escapism is immersion in work or creative pursuits. But meditation isn’t just another way to avoid or become numb to the world. Instead it develops the capacity of awareness of the moments of quiet that already exist between our thoughts. They’re there already; they just need to be noticed. These moments of nothing are vital. It helped me to understand like to a piece of music has rests that provides moments of quiet that are indispensable to the music, or similar to how a painting has areas of restraint, areas with nothing happening that are necessary for us to better see what is happening. Without the moments of nothing, music, art, and our minds are just chaos. We meditate to find that nothing. Once we can find these gaps between our thoughts, we can work to sustain them a little longer each time. It’s not about stopping our thoughts or fighting to get them to settle down, but just noticing those slivers of peace between them.

“Music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.” – Mozart

Once we can find the spaces between the cacophony of thought, in that tiny gap between trigger and reaction, we can reclaim our agency to decide how to act. When we focus on the nothingness instead of following our personal thoughts and feelings, then we’re no longer dragged along by the drama in our lives. Meditation helps to develop an awareness of our automatic processes enough to avoid being hijacked by them.

And then, once we grasp these moments of nothingness, we can begin to appreciate that we aren’t our thoughts. The self isn’t just a collection of ideas that come to us wrapped up in a brain in a stable body. We exist in the moments between our thoughts as well. And when we start to look at who we are, if it’s not our thoughts, then we’re nothing, but in the best possible way. We can be without having to be something. I can never remember this for long, though. I set up reminders because I’ve found nothing more useful to distance myself from ideas or arguments or expectations than mere observation of the inner world as distinct from identity.

To take it just a little further, this craving we all share comes from adhering to the illusion of having a separate self. We meditate to find that we don’t exist as a distinct entity. This is great because then we don’t have to worry about doing all the things!! We’re all part of a bigger ocean. So when that little voice in our head is talking shit to us, telling us we’re lazy or boring or ugly, it’s not us that’s doing the talking or listening. It’s just something that’s happening, an event that we’re free to ignore, losing interest in it like it’s a bad TV show. And then through this awareness of the illusion of individual boundaries we can start to better connect to others who might seem very different from us because they’re also part of this ocean of nothing!

“This seemingly solid, concrete, independent, self-instituting ‘I’ under its own power that appears actually does not exist at all.” – Dalai Lama

It reminds me of experiencing an understanding of the existentialist proposition of taking full responsibility for our actions. We tend to see taking responsibility as a burden that we want to avoid, so we blame anything else we can find besides our own will. But once we get in the habit of saying, “Yes, I chose to do this,” we begin to see the radical freedom that comes with accepting responsibility for all we do. Once we start saying we chose it, then we recognize the choices that exist to us. Similarly, once we have the courage to accept that our thoughts aren’t our self, and stop clinging to that idea of individual identity, then we can start to see the space we have to stretch into as we embrace our own emptiness.

We’re not comfortable with emptiness, so we try to fill it, grasping at fixing problems or finding that one solution to solve our issues instead of coming to terms with our true nature. People worry that finding the emptiness within will be like falling through space, but it’s more like floating in warm water or opening the door to an empty house that is rife with possibilities. Our dissatisfaction with ordinary life provokes us to seek a permanent euphoria, but everything is constantly changing anyway, so who really benefits from elevating the importance of particulars?

Sounds a little out there, I know. But many people believe in the idea of a subconscious and conscious mind, which then splits the internal self in two: one part of us there to scrutinize the other part in an internal battle to fix ourselves. There’s no proof of this subconscious, but it’s become common enough that most of us accept the theory without question. However, if we can buy into that, isn’t it possible, instead, to believe in the oneness of the self with the universe? The question becomes, which is a more useful understanding of the self when it comes to releasing our cravings?