by Marie Snyder

Freud got some things right, and this isn’t a post to slam him. But he understood the whole concept of the unconscious mind upside-down. It’s a lot like Aristotle’s science, with the cause and effect going in the wrong direction. It’s still pretty impressive how far they got as they laid the foundations for entirely new fields of study. I assimilated most of what’s below from neuropsychologist Mark Solms’s 2019 Wallerstein Lecture. It’s fascinating, but over three hours long, and he talks really fast! I’m just a novice in this field of affective neuroscience, and I don’t know enough to be sure his confidence in this theory is warranted, but it’s a really interesting way to understand ourselves.

Freud got some things right, and this isn’t a post to slam him. But he understood the whole concept of the unconscious mind upside-down. It’s a lot like Aristotle’s science, with the cause and effect going in the wrong direction. It’s still pretty impressive how far they got as they laid the foundations for entirely new fields of study. I assimilated most of what’s below from neuropsychologist Mark Solms’s 2019 Wallerstein Lecture. It’s fascinating, but over three hours long, and he talks really fast! I’m just a novice in this field of affective neuroscience, and I don’t know enough to be sure his confidence in this theory is warranted, but it’s a really interesting way to understand ourselves.

Here’s the gist of it.

Freud figured that the conscious part of our mind, the part that’s aware of our world and ourselves, was something that could be located in the brain, but he placed it in the cerebral cortex, the outermost area that does all the thinking. That makes sense because it’s how we connect to the outside world. However, according to Solms, the conscious part is actually way in the innermost region of our brain at the upper part of the brain stem. This has been backed up with studies on people with encephalitis that have found that it’s not essential to have a cortex in order to have emotional responses and an awareness of the world and self. When neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp had his students guess which rats didn’t have a cortex, they guessed incorrectly because the rats missing this intellectual part of their brain were friendlier, more lively and interactive; they didn’t have a cerebral cortex inhibiting their movement toward total strangers much like happens with the subdued inhibitions of friendly drunkenness.

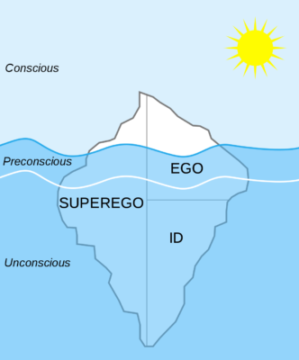

So Freud got the placement wrong. But even more important is which parts of us are within our conscious awareness. He famously divided our mind into three: id, ego, superego, much like Plato’s tripartite soul, and deduced that the id – our drives for pleasure – were entirely unconscious. But Solms explains that many in the field today argue that our affective center, the forces that push us toward pleasure and away from pain, is necessarily conscious in order to make us aware of our needs. And then decision making, which happens in the cerebral cortex, is mainly – like, 95% – automatic, without consciousness.

So Freud got the placement wrong. But even more important is which parts of us are within our conscious awareness. He famously divided our mind into three: id, ego, superego, much like Plato’s tripartite soul, and deduced that the id – our drives for pleasure – were entirely unconscious. But Solms explains that many in the field today argue that our affective center, the forces that push us toward pleasure and away from pain, is necessarily conscious in order to make us aware of our needs. And then decision making, which happens in the cerebral cortex, is mainly – like, 95% – automatic, without consciousness.

How can that be? We’re all aware of thinking right this moment, right? It all has to do with the efficiency of our memory systems.

Adding to the work of Joseph LeDoux, Solms explains that our short term memory is in our consciousness, but it’s very small and can only fit a few things at a time. So we’re aware of what we’re thinking in the moment, but then these thoughts and memories we have need to be consolidated into longterm memories. Because the space in the consciousness is small, and it takes a lot of energy to maintain consciousness, we automatize our memories as much as possible so we don’t have to think about them, and they become nondeclarative, or unconscious. Some memories can be brought back into consciousness sort of, like facts and events, but they’re always a reconstruction of reality. Each time we retrieve an event, the conscious representation of an event is amplified by the emotional arousal system which creates a new emotional memory. And some even can never be retrieved. Freud was right about how defence mechanisms work to a point, but repressions are different by kind. Denial, regression, projection, etc. can be pointed out and worked with within our conscious mind, but repressions are gone for good. But we don’t need to reconstruct the past. The goal of “doing our work” isn’t to remember the past, but to notice when we’re headed down there in the present, and change course.

What does that look like?

Further to the idea that our affective center or drives are necessarily conscious, Solms explains them under three broad categories: bodily, sensory, and emotional. They all function to alert our body that we’re outside a narrow range of comfort necessary for survival. For example: we’re hungry (body), or too close to the fire (sensory), or too far from mum (emotional). These affects all provoke us to act in order to get back to homeostasis – to get back in the comfortable range, so they’re necessarily conscious or else they wouldn’t be able to get us to change our behaviour. Each arousal is a measure of deviation from an internal “settling point” that we aim for, and that can be different for each of us. We’re not aware of the setting points, but we are aware of the discomfort. When we feel discomfort, we predict what will work to get us back to homeostasis (e.g. try eating something or moving away from the heat or crying out for mum).

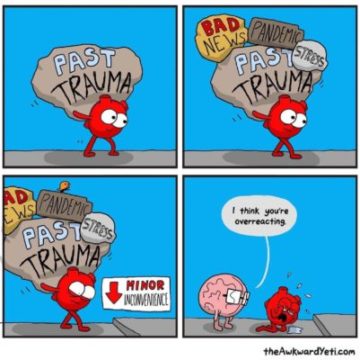

The emotional systems are most complex, and we often get our predictions wrong, particularly as children. Maybe we cry out for mum, and she doesn’t come, so we give up. But then we follow these predictions over and over anyway, which provokes maladaptive behaviours as adults, like, perhaps, never asking for help when we need it.

There are just seven primary emotions in this system, and affective neuroscientists write them in all caps to distinguish them from other uses of these common words:

- SEEKING – exploring the world

- RAGE – frustration when we’re impeded from getting what we need, territorial

- FEAR – a type of anxiety that helps us avoid harm

- LUST – horniness

- CARE – a desire to nurture and attach to others

- PANIC – a type of anxiety or distress when we’re separated from others

- PLAY – joy with others in order to develop boundaries of dominance

To clarify that last one, most imaginative games are hierarchical (cops/robber, doctor/patient, mom/baby, teacher/student), which allow children to play at being leader and being led. But Solms explains that it has to be a 60/40 split. We’ll tolerate being dominated about 60% of the time, and then it’s our turn. This type of play is vital to learn social boundaries and limitations to power. It’s a problem when it’s no longer joyful because then it has become real, and then other affects take over, like RAGE and FEAR.

So, what drives us isn’t so different from the drives of your garden variety kitten.

As I’m writing these words, though, I might argue that I don’t need to do it for survival of any kind. Yet I still feel inexplicably driven to write things regardless of an audience or remuneration of any kind. What’s going on when we are driven towards a creative pursuit?

I understand it as a form of SEEKING. What a kitten looks for in their awareness of the environment is much more limited: beyond food and the warmth of a lap to curl up in, it looks for small moving objects to pounce on. By contrast, our awareness of the world is not contained to external objects, but also the ideas moving around inside that come into view briefly, then quickly disappear. I’m trying to catch them and pin them down. Many people don’t have that internal seeking drive in the same way, and are driven differently. Perhaps people who are content to sit and watch other people have reached homeostasis. Buddhist philosophy suggests we’ll be happier if we can let go of all this striving, and I can accept the quest to let go of things, but I’m still not on board to let go of my drive to capture ideas.

Of course, these seven emotional states, or affects, combine in different ways. LUST and CARE together provoke pair bonding. Then, even as adults, we add in PLAY to work through boundaries, and have times of PANIC when apart, which reminds us of how necessary that person is to us. Then FEAR when they’re driving in bad weather, and RAGE when being with them might mean compromising on the career we wanted, and then guilt (RAGE + CARE) because we said something hurtful, and grief (PANIC + CARE) when they leave.

Back to that automation system that makes our memory system so efficient. Sometimes a system is automated as a child, before we knew any better, and it doesn’t work for us anymore, so it needs adjusting. But it’s been so long that it can take ages to rewire That move to cut all ties because their needs got in the way of our plans instead of making them part of our plans, that wasn’t something we wanted to say, or even decided to say, but it just came out automatically. It was automated a long time ago when cutting someone off was the most efficient route to survival. That could be from a caregiver not being there when they were needed or even from just a random mean kid at school. We blocked them out, recognized the efficiency of that move, and did it again and again, making a neural pathway that made that route the easiest to take the next time we were frustrated by someone.

It’s like walking the same path in the snow to work, and the more we do it, the deeper the path gets and easier it is to navigate. And then one day we realize there’s a much nicer way to get there, one that doesn’t chase people away at the first conflict. We have to do a lot of work to ignore the groomed trail and do some bushwhacking to carve out a new route. It’s so much effort, and we keep forgetting about it and just go the old way instead, mainly if we’re tired or overwhelmed or just lost in thought and not even aware we took that old path until we’re at the end of it.

Since our brain does most of our thinking for us, it’s this emotional wrangling that we’re left to sort out. It doesn’t always feel emotional. It often feels very rational as we sit down with a pros/cons list to make a clear headed decision: do I stay or do I go, but that rational decision is CARE and PANIC and RAGE all trying to get back to homeostasis, back to their settling points, in the most efficient way possible.

It’s not that different from Hume‘s insistence that we don’t act without sentiment guiding us.

Those who would resolve all moral determinations into sentiment, may endeavor to show, that it is impossible for reason ever to draw conclusions of this nature. . . . What is honorable, what is fair, what is becoming, what is noble, what is generous, takes possession of the heart, and animates us to embrace and maintain it. . . . Render men totally indifferent towards these distinctions; and morality is no longer a practical study, nor has any tendency to regulate our lives and actions.

Reason alone lacks all motivation. But our emotionally driven decisions, that push to get back to a settling point, can so easily be hidden from us by a defence mechanism that leads us to ignore the signals our nervous system is telling us about our place in the world. For instance, we may have learned to satisfy feelings of guilt by rationalizing why it’s okay that we yelled at that person or took more than our fair share. We have to uncover all the layers of defences to get to the primary emotion that’s working to get back to a comfortable range.

Reason alone lacks all motivation. But our emotionally driven decisions, that push to get back to a settling point, can so easily be hidden from us by a defence mechanism that leads us to ignore the signals our nervous system is telling us about our place in the world. For instance, we may have learned to satisfy feelings of guilt by rationalizing why it’s okay that we yelled at that person or took more than our fair share. We have to uncover all the layers of defences to get to the primary emotion that’s working to get back to a comfortable range.

We’re at a place in our human trajectory where we might see whether or not we really do have some sentiment in common, as Hume called it, some universal morality, or if we really can be convinced by external forces that it’s okay to have a several homes when others have none, or use more fossil fuels than necessary for our survival, jeopardizing the longterm survival of our children, or walk around unconcerned if we’re spreading a harmful virus.

Can society render us indifferent enough to self-destruct?

Because here’s another part of the story discussed by interpersonal neurobiologist Louis Cozolino and psychiatrist Dan Siegel: The neurons in our body (in the “big” brain in our skull, the “little brain” lining the entire GI tract from esophagus to rectum, and our entire nervous system) communicate by sending messages along a tiny space between neurons through an electro-chemical process. The spaces between neurons is where all the action happens. And the same process happens between people! Sight, sound, smell, are all forms of energy moving molecules connecting us through the synaptic spaces between us. The whole world is like a synaptic gap. This can help confirm the idea that we’re not separate selves out here, but entirely interconnected with the rest of the world, the way our neurons are interconnected within a membrane we use to differentiate ourselves! It creates an analogy that clarifies that, even if we’re not individually prominent, we are each vital to the system. Allowing part to be significantly harmed, harms the whole.

The settling points are an evolutionary mechanism that enables us to survive. It would make sense, then, that the interdependence of the system would make us feel discomfort when others are adversely affected by our actions. It’s all a balancing act. We’re driven to be with people, distressed when they leave, but also constantly finding our boundaries with them and outraged when our needs are trampled, so we continue to look for ways to mend our connections. As Charles Taylor says, “The general feature of human life is its fundamentally dialogical character.” But we’ve taken such an instrumental stance to ourselves and others that we “may have lost the capacity to listen to this inner voice.” We have to dig beneath our culture’s fabrications that provoke us toward a belief that we can survive if we win and others lose, and find that authentic balance unmarred by harmful agendas.

It’s as if our biology is equipt to find an inner morality – an inner means of working and living interdependently, but our current collective defensiveness is shielding us from acknowledging this to our own detriment. What Freud got right is the understanding that we have a tiny part of our mind for conscious thought, and we have to use it to dig through defences in order to make sense of our personal troubles through a dialogue with another human being. He also lamented the efforts of society to steer us in the wrong direction. We’re being driven right off a cliff at this point, with human caused issues that we continue to avoid working on, often because of a personal and collective refusal to enable this natural homeostasis of primary emotions, ignoring that 40/60 domination boundary and merely sedating our PANIC, our loneliness and alienation from the instrumentalization of humanity.