by R. Passov

Sometimes, when you least expect to, you learn something about your country and the toll it has imposed on certain of its citizens. In ancient times these learnings weren’t so serendipitous. During WWII, for example, you would have known folks on your block who served and came back. And some who didn’t come back.

Sometimes, when you least expect to, you learn something about your country and the toll it has imposed on certain of its citizens. In ancient times these learnings weren’t so serendipitous. During WWII, for example, you would have known folks on your block who served and came back. And some who didn’t come back.

Even in that near-ancient time of the Vietnam War, likely you would have known folks in both classes. That war, or at least the US involvement, officially lasted about eight years. Over three hundred thousand US service personnel were injured and approximately 50,000 US lives were lost (and countless others.)

The Iraq war also lasted, by some measure, eight years – 2003 to 2011. Over that stretch, about 4,500 US service members made the ultimate sacrifice. Another 45,000 were wounded. (These figures are purposely misleading as they omit approximately the same number of deaths and injuries suffered by ‘contractors.’ I’ll leave this bit of Orwellian misdirection to another day.)

The US involvement in Afghanistan lasted about twenty years. Approximately 2,500 service members gave their lives while ten times that number were injured.

Judging by the ratio of wounded to dead, one was more likely to survive in Afghanistan than in Vietnam, and even more likely than in WWII. This is understandable; we’ve had over fifty years to improve our medical capabilities. But one consequence of advances in medical technology is the violence in war, when measured in such a narrow way, seems less so.

*

“They divorced when I was six,” our Uber drive offered.

“We were so poor,” he said, “we had chickens because they could feed themselves; what you’d call free range now.” This tinge of snark caused me to look afresh at a big man in a little car, taking us to the airport near Charleston.

“Well we had them for the eggs. And every once in a while we had to eat one. When you’re that poor you figure things out, like how to cook.”

He knew he was a sight and knew, in one way or another, we were going to delve. Like a good Uber driver, he was ready to share his origin story. Read more »

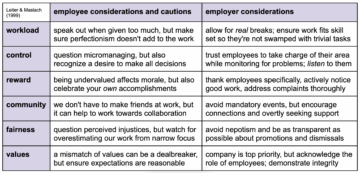

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

Eugene Russell, a piano tuner interviewed by

Eugene Russell, a piano tuner interviewed by

Sughra Raza. Untitled. June, 2014.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. June, 2014.

In philosophical debates about the aesthetic potential of cuisine, one central topic has been the degree to which smell and taste give us rich and structured information about the nature of reality. Aesthetic appreciation involves reflection on the meaning and significance of an aesthetic object such as a painting or musical work. Part of that appreciation is the apprehension of the work’s form or structure—it is often the form of the object that we find beautiful or otherwise compelling. Although we get pleasure from consuming good food and drink, if smell and taste give us no structured representation of reality there is no form to apprehend or meaning to analyze, so the argument goes. The enjoyment of cuisine then would be akin to that of basking in the sun. It is pleasant to be sure but there is nothing to apprehend or analyze beyond an immediate sensation.

In philosophical debates about the aesthetic potential of cuisine, one central topic has been the degree to which smell and taste give us rich and structured information about the nature of reality. Aesthetic appreciation involves reflection on the meaning and significance of an aesthetic object such as a painting or musical work. Part of that appreciation is the apprehension of the work’s form or structure—it is often the form of the object that we find beautiful or otherwise compelling. Although we get pleasure from consuming good food and drink, if smell and taste give us no structured representation of reality there is no form to apprehend or meaning to analyze, so the argument goes. The enjoyment of cuisine then would be akin to that of basking in the sun. It is pleasant to be sure but there is nothing to apprehend or analyze beyond an immediate sensation.

Bill Gates has long been one of the world’s leading optimists, and his new documentary, “What’s Next,” serves as a testament to his hopeful vision of the future. But what makes Gates’s optimism particularly compelling is that it is grounded not in dewy-eyed hopes and prayers but in logic, data, and an unshakable belief in the power of science and technology. Over the years, Gates and his wife Melinda, through their foundation, have invested in a wide array of innovative technologies aimed at addressing some of the most pressing issues faced by humanity. Their work has had an especially transformative impact on underserved populations in regions like Africa, tackling fundamental challenges in healthcare, energy, and beyond. In this new, five-part Netflix series, Gates showcases his trademark pragmatism and curiosity as he engages with some of the most complex and important challenges of our time: artificial intelligence (AI), misinformation, inequality, climate change, and healthcare. His approach stands out especially for his willingness to have a dialogue with those with whom he might strongly disagree.

Bill Gates has long been one of the world’s leading optimists, and his new documentary, “What’s Next,” serves as a testament to his hopeful vision of the future. But what makes Gates’s optimism particularly compelling is that it is grounded not in dewy-eyed hopes and prayers but in logic, data, and an unshakable belief in the power of science and technology. Over the years, Gates and his wife Melinda, through their foundation, have invested in a wide array of innovative technologies aimed at addressing some of the most pressing issues faced by humanity. Their work has had an especially transformative impact on underserved populations in regions like Africa, tackling fundamental challenges in healthcare, energy, and beyond. In this new, five-part Netflix series, Gates showcases his trademark pragmatism and curiosity as he engages with some of the most complex and important challenges of our time: artificial intelligence (AI), misinformation, inequality, climate change, and healthcare. His approach stands out especially for his willingness to have a dialogue with those with whom he might strongly disagree. I lived in Philadelphia in 1977 and would go to the Gallery mall on Market Street, a walking distance from our river front apartment. One day, around lunch, I decided to get Chinese food at the food court and looking for a place to sit, I asked two older ladies if I could sit at their table, since the place was packed. As I was picking through the food, separating the celery and water chestnuts, one of the old ladies said

I lived in Philadelphia in 1977 and would go to the Gallery mall on Market Street, a walking distance from our river front apartment. One day, around lunch, I decided to get Chinese food at the food court and looking for a place to sit, I asked two older ladies if I could sit at their table, since the place was packed. As I was picking through the food, separating the celery and water chestnuts, one of the old ladies said