by Lei Wang

[This is part of a series on bringing magic to the everyday through imagination.]

Someone once told me the trick to fasting: take long walks. That way, your body believes you are at least on the search for food and temporarily forgets its hunger. When you’re in the mode of actually solving the problem, the problem tends to go away, as opposed to endless rumination about the problem. Then again, the person who told me this was the kind of person who could do things merely because she knew they were good for you. This was another one of those common sense yet counterintuitive things I often fail to put into practice, along the lines of how using energy somehow begets energy, while sleeping all day makes you sleepier.

I rarely fast, but I often find myself hungry and slightly irritated—I am one of those people—and wonder if I can take the trick a step further, using my imagination. Hunger already lends itself to animal metaphors—“I could eat an elephant,” “I’m a hungry hippo”—so why not take it all the way? On the sidewalk nearing noon, I become a large savannah cat chasing my wildebeest. At my desk, a squirrel savoring each nibble of a stolen cashew. Or a crocodile lying in wait by the marsh grass/microwave. I must, in fact, focus and stay still to get my lunch, and this calms me down. Hunger starts to feel less like a problem and more like a game. Bringing meaning to things: this is what humans do, isn’t it? And we can just make up the meanings.

Of course, one can also just have a granola bar. I’m not even concerned so much about true physiological hunger—this being a sphere of excess—but the psychological kind. I am interested in dealing with our evolutionary wants, our programmed desires, with creative and unpunishing ways to choose otherwise. In other words: how do we not act like dogs when it comes to the food instinct, even if (let’s face it) we probably all long for the life of a very good middle-class dog?

Perhaps it is because I am not very disciplined, or not very good with shoulds. I am thinking of the problematic thing parents used to say to children about not finishing their peas (not sure what millennial parents say to children now): “Think of all the starving children in Africa!” As in, they should be relived to not be so deprived and ashamed for not being more grateful. This, I think, is a failure of imagination. It uses the rational mind, not the creative one.

Why do fussy toddlers so enjoy food coming at them like a bird, like a plane? Does the hovering spoon trigger an ancient chameleon consciousness? As a child, I imagined I was a giant eating forests of broccoli trees. A friend who later became a mathematician said he loved numbers vs. alphabet soup. These are better uses of the imagination.

Sometimes I pretend I’ve come from some era when salt was rare and precious; the word salary, after all, comes from salt, because Roman legions accepted it as payment. Qing Dynasty emperors had salt at their tables, but few others in China did at the time. I like to remember salt as luxury, but not use salt as guilt. Also, the Chinese emperors never had lemon tarts or chocolate eclairs. And all that fanfare at every meal must be exhausting.

A philosophy professor once told me there are some cultures where sex happens in public, while eating in front of others is taboo and happens in private. This seems to be true of the Trobrianders of Papua New Guinea, but simply imagining it feels a little scandalous, makes me more aware of how strange and intimate eating really is. I like to imagine that the first kiss in the world came about from two creatures sharing food, millennia before The Lady and the Tramp: a tuber for you, from one naked mole rat to the other, their whiskers touching.

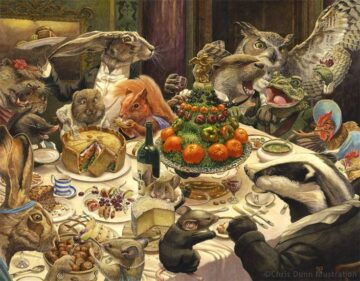

The popular whimsical children’s fantasy series, Redwall, featuring talking mice, otters, and hedgehogs, is famous for its lush depictions of food. Between bouts of fending for their medieval abbey, the animals have marvelous feasts featuring such woodlands-inspired dishes as oat scones in greensap and maple sauce, devilled barley pearls in acorn puree, and jam-filled willowcake with meadowcream, accompanied by flagons of cowslip cordial, dandelion ‘n burdock fizz, and elderberry wine. The author, Brian Jacques, grew up in Liverpool, England during World War II, under strict food rationing. The only fruit he had as a child were apples; he had heard of bananas, but thought they were fiction. Meanwhile, he flipped hungrily through his mother’s recipe books and learned to make things up. “I just think of what I would like to eat and embellish it,” Jacques said.

What I remember most about Katherine Rundell’s YA fantasy book, Impossible Creatures, aren’t the impossible creatures—dragons and griffins and such—but the description of a sack of fruit: “He had been given a woven bag of apples, of plums and pears and apricots: dryad fruit, like nothing else on earth. They tasted still-living; fruits with opinions and jokes and laughter in them.” I imagine the little ruby seeds inside pomegranates are gossiping with one another, cozy, and it deepens my experience of the pomegranate. I want to taste the food of dryads, of fairies. Ambrosia. The food of literature. Babette’s feast. Tita’s wedding cake in Like Water for Chocolate that makes everyone pine for love. The lemon cake in The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake. Proust’s madeleine, of course, though it was never really about the madeleine.

Mindfulness classes are often teaching practitioners to pay attention more deeply to the world around them, the world as it is. A common exercise involves an orange, savoring each pulp, or chewing a raising for minutes on end, noticing every sensory detail. The point is to really pay attention to them and their sensory qualities, perhaps for the first time, and while not watching TV or otherwise spending time in the mind instead of in the mouth. As someone who has meditated for the last fifteen years, I understand this approach very well: yes, we should pay more attention to oranges!

But I would also like to add a layer of fantasy to this reality: what if, for example, we pretended we were the protagonist in the fantasy novel The Priory of the Orange Tree, in which all her magic powers—the ability to conjure light and flame—comes from a sacred orange tree, the only one in the world? “The gift of the orange tree—a magic of fire and wood and earth,” the book describes it. The protagonist has not tasted an orange, has not tasted magic in her veins, for years. What is this orange were that orange?

In a way, all meditation is about becoming more like a child again, with a child’s wonder at the world, a child’s appreciation. Part of a child’s delight is a consequence of newness: the brain pays extra attention to the unfamiliar, unsure whether it’s danger or boon. That’s why the first day in a new city can feel so long and rich: the mind cannot yet predict what will happen and so your senses are extra alert. You literally see, smell, hear, taste, and touch more. Scientists call it habituation when the brain gets used to something and stops noticing it, the same-old same-old that fades into the background. Habituation is the opposite of excitement, of aliveness. Travelling can make one feel alive like a child again, or falling in love, or any number of things that take us out of our familiar habits.

Imagination is also a kind of sensory travel: “Imagination is not an intellectual capacity,” says the poet Jorie Graham. “It is something sensorial.” By imagining context, we can fall in love with ordinary things, the way Billy Collins does, in this poem, “Aimless Love,” with a bowl of broth, “steam rising like smoke from a naval battle.” A poetic approach to living, or a way to get a kid interested in playing at war (before knowing any better) to eat hot soup.

Of course, imagination can also work the other way, as in, we can fall out of love with things. Once, a friend came over while I had a vase of ripe lilies in the living room (I would like to imagine they were from a lover, but I can’t remember anymore). I love the smell of lilies, and exhorted him to smell them, to enjoy one of the pleasures of life. “Mmm smells like baloney,” he said, which was unfortunately true and rather ruined their romanticism for me (this same friend also likes to point out, whenever anyone is eating shrimp, how they are basically giant bugs). I told him he had done me wrong, and he said, “But now when you smell baloney, you’ll always think of lilies.” A good use of the imagination: upgrading a mystery meat.

I once watched a video of the self-help guru Tony Robbins curing a man of his pizza addiction (my Italian boyfriend at the time refused to watch this video). First he has the man imagine his dream pizza: hot, with mushrooms, sun-dried tomatoes, and extra cheese. So far so good. Then he continued to ask him to imagine: the same pizza cold, after the grease has congealed, the pizza with meat on it (the man hated sausage and pepperoni for some reason), the pizza after days and days. He asked the pizza addict, again and again, to truly use his senses to imagine the meat rotting, the cheese going rancid, until eating it became unimaginable. The man really looked like he wanted to throw up on stage. This was similar to the way Tony Robbins, early in his career, apparently cured a coaching client of a smoking addiction by commanding the client to smoke as many cigarettes at a time as possible in a windowless hotel room. By the end, the client was so overwhelmed he never wanted to smoke again, and supposedly, it lasted. But now, Tony Robbins could use the imagination instead and no one had to eat rancid pizzas. (If he had known about the imagination earlier, he wouldn’t have had to breathe all that secondhand smoke.)

I like using the imagination as a kind of problem-solving. When confronted with an unsatisfactory meal, what if you pretended you were a snobby food critic? Suddenly, there is a purpose to the disappointingly limp linguine, the too-fishy ceviche. Or what if you had been a nun for years, subsisting only on cold gruel? Could it taste okay to you, this only slightly burned oatmeal? A friend became a vegetarian because he could not stop imagining the living chicken as he was eating it. I am not yet a vegetarian, but I imagine this is a good method to become one.

One of my favorite meditations, via Regena Thomashauer, otherwise known as Mama Gena, who teaches women the art of feeling pleasure, is simply the meditation of feeling delicious. Imagine you are delicious. Feel what that feels like. That’s all. But of course, I add a little more: imagine you are your own favorite food, inside out. When I do this, I feel a buzz from head to toe; deliciousness feels somehow like soda fizz. I imagine every cell of me bursting, juicy. Forget hunger. I imagine I am ready to be eaten and somehow, this makes me full.