by Marie Snyder

“As the world falls around us, how must we brave its cruelties?” —Furiosa

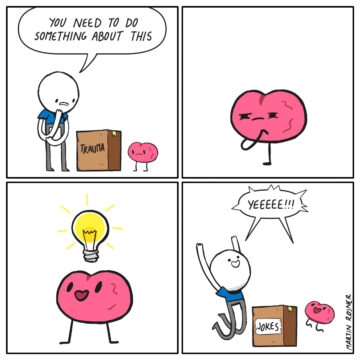

Imprisoned climate activist, Roger Hallam, recently wrote about the necessity of expanding emotional well-being as we face bleak events happening around the world. While climate scientists try to “help people through the horrific information that they are being given,” they also need a way to manage their emotional reactions. We can no longer afford to merely distract ourselves from the inner turmoil. Beyond climate, we could very well be entering into a period of much greater conflict at a time of even more viruses, some destructive to our food system. When the watering hole gets smaller, the animals look at one another differently.

To move forward with compassion, at a time when divide and conquer strategies have created polarization and infighting, seems to require an effort from each one of us.

Hallam writes,

“We might want to think about why saint-like people are enormously influential, even powerful. . . . They see the world as dependent upon the mind. . . . They are not enslaved by the world; their minds are intent, driven even, to change it. They do not see this as an end in itself.”

He explains the journey toward collective action as beginning with exploring the self as it relates to reality. The part of interest to me is this:

“Some people are so into themselves that they find it almost impossible to get out of themselves. They are stuck, enmeshed. Children are often like this. They are literally overwhelmed by their emotions. . . . You see it a lot in prison–people so full of their distress, their anger, and rage, they cannot see themselves at all. . . . The ability to reflect on yourself, on your emotions and your behavior, leads on to a more general idea, and that is transcendence. This might be described as a deep ability to move outside of oneself, to look at oneself from the outside, simply to watch. . . . The more you practice doing it, the stronger you get at doing it. . . . The essence of being human is nothing to do with our being in this world–it is to do with having a choice.”

The ability to choose to be responsive instead of reactive can be developed and refined through intentional introspection. This isn’t anything new; it’s an old truth ignored until it becomes crucial to our survival. Read more »

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.