by Gary Borjesson

In 1956 when this work was begun I had no conception of what I was undertaking. At that time my object appeared a limited one, namely, to discuss the theoretical implications of some observations of how young children respond to temporary loss of mother. —John Bowlby (opening sentence of his seminal book, Attachment, 1969)

Note: I always disguise the identities of patients discussed in my writing.

A patient described the dramatic dance he was in with his longtime partner as “go away closer.” She’d be warmly attentive, which drew him closer; but as soon as he stepped in, she would step back. He asked whether she wanted to go to a concert, and she was enthusiastic. But after he’d bought tickets, she made excuses and suggested he invite a friend instead. Confused and hurt, he’d move away, partly to protect himself but also to punish her. Paradoxically, this seemed to attract her. And the dance would begin again. He felt as if she were gaslighting him, but he knew she wasn’t, or at least not consciously.

Attachment theory offers an explanation of such primitive (unconscious and instinctive) relationship dynamics. Attachment patterns, shaped by early interactions with caregivers, are impressively durable: Secure versus nonsecure patterns discernible by 12 months of age correlate with adult attachment behavior roughly 50% to 60% of the time.

In this essay I offer an overview of attachment, an increasingly influential lens through which to understand how we relate to others—and who we are. For our “self” is fundamentally relational, just as our brains are fundamentally social. We become our selves through engaging with the world, and attachment science reveals how our early experience disproportionately affect who we become and how we relate. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017. If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

In reading about attachment theory,

In reading about attachment theory,

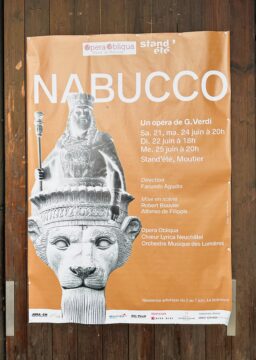

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.