by Daniel Gauss

COVID-19 revealed something terrifying about modern democracies: they are especially vulnerable to ambiguous threats, which can become magnified into national disasters. A virus that was neither mild enough to ignore nor lethal enough to unify a response managed to throw the United States into prolonged disarray causing unnecessary and severe harm.

If COVID-19 had been a super deadly, super-virus, we would have reached a quick consensus on how to fight it, out of necessity. Throughout our history our nearly always divided nation has regularly rallied around the flag and united political divisions to meet major crises. On the other hand, if the virus had been super weak, we could have completely ignored it.

It was its position in the murky middle, neither trivial nor catastrophic, that proved most damaging: a Goldilocks zone where uncertainty overwhelmed coordination. The most insidious thing about COVID-19 was that it did not demand an unambiguous response. By its very nature, the virus thwarted decisive action in the largest democracies. There could never be a clear consensus in a fractious democracy on how to treat it or even how to talk about it. It engendered anxiety and undermined unequivocal action.

If you had wanted to develop a perfect virus to afflict a troubled democracy – one already splintered by culture wars, plagued by distrust in institutions and weakened by an over-saturated information environment – it would have been COVID-19. The pandemic for us, therefore, was a political, psychological and social crisis, one that exposed the fragility of decision-making in democratic systems. Read more »

In my last

In my last

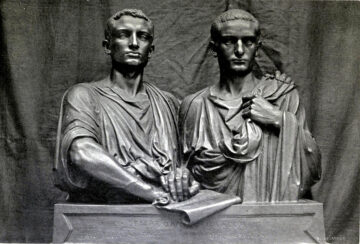

In the first part of this column last month, I set out the ways in which the separation of powers among the three branches of American government is rapidly being eroded. The legislative branch isn’t playing its part in the system of “checks and balances;” it isn’t interested in checking Trump at all. Instead it publicly cheers him on. A feckless Republican Congress has essentially surrendered its authority to the executive.

In the first part of this column last month, I set out the ways in which the separation of powers among the three branches of American government is rapidly being eroded. The legislative branch isn’t playing its part in the system of “checks and balances;” it isn’t interested in checking Trump at all. Instead it publicly cheers him on. A feckless Republican Congress has essentially surrendered its authority to the executive.

I drive in silence these days. That in itself is nothing new. For years, my solo road trips across America have featured long stretches of near silence. Nothing coming from the speakers. No talk, no music, no pleading commercials. Just the whir of the road helping to clear my mind.

I drive in silence these days. That in itself is nothing new. For years, my solo road trips across America have featured long stretches of near silence. Nothing coming from the speakers. No talk, no music, no pleading commercials. Just the whir of the road helping to clear my mind.

Junya Ishigami. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2019.

Junya Ishigami. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2019.

By many measures wealth inequality in the US and globally has increased significantly over the last several decades. The number of billionaires has increased at a staggering rate. Since 1987, Forbes has systematically verified and counted the global number of billionaires. In 1987, Forbes counted 140. Two decades later Forbes tallied a little over 1000. It counted 2000 billionaires in 2017. In 2024 it counted 2,781, and in March this year it counted 3,028 billionaires (a 50% increase in the number of billionaires since 2017 and almost a 9% increase since 2024).

By many measures wealth inequality in the US and globally has increased significantly over the last several decades. The number of billionaires has increased at a staggering rate. Since 1987, Forbes has systematically verified and counted the global number of billionaires. In 1987, Forbes counted 140. Two decades later Forbes tallied a little over 1000. It counted 2000 billionaires in 2017. In 2024 it counted 2,781, and in March this year it counted 3,028 billionaires (a 50% increase in the number of billionaires since 2017 and almost a 9% increase since 2024). Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of

Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of

There was a prevailing idea, George Orwell wrote in a 1946 essay

There was a prevailing idea, George Orwell wrote in a 1946 essay