by Claire Chambers

Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of state-of-the-nation – or, more accurately, ‘state‑of‑the‑world’ – novels tend to arrive clad in yellow dust jackets while bearing short, even one‑word, titles. I’m thinking of books like Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, Asako Yuzuki’s Butter, and Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface. Published in English within a year of each other, in 2023–2024, perhaps their look comes from the fashion moment yellow is having. Although the trending shade is a softer, creamier hue than the bright pop of the novels’ daffodil covers, the books’ appearance is on point for this moment in the mid-2020s. This cheerful styling helps make bookshops’ cash registers sing, appropriately enough, like canaries. In a not dissimilar way to Tadej Pogačar, who has just won the Tour de France in his yellow jersey, these books are some of the leading literary winners of the past half decade.

Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of state-of-the-nation – or, more accurately, ‘state‑of‑the‑world’ – novels tend to arrive clad in yellow dust jackets while bearing short, even one‑word, titles. I’m thinking of books like Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, Asako Yuzuki’s Butter, and Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface. Published in English within a year of each other, in 2023–2024, perhaps their look comes from the fashion moment yellow is having. Although the trending shade is a softer, creamier hue than the bright pop of the novels’ daffodil covers, the books’ appearance is on point for this moment in the mid-2020s. This cheerful styling helps make bookshops’ cash registers sing, appropriately enough, like canaries. In a not dissimilar way to Tadej Pogačar, who has just won the Tour de France in his yellow jersey, these books are some of the leading literary winners of the past half decade.

More significantly, this branding evokes both the social menace of the yellowjacket wasp and the macabre suspense of the TV thriller with the same waspish name. Such books carry the visual sting of a cautionary tale, even though the trio of novels are also often very funny. Their spines flash like hazard tape or symbols for radioactive waste and chemical toxins. The promise, or threat, is for narratives smarting with ecological or technological dread and familial devastation. Texts like The Bee Sting, Butter, and Yellowface are comic, edgy, and hyper-current. The literary exemplars tacitly, and probably unconsciously, recall the work of Jordan Peele. This African American film director makes movies about social division with one- or two-word titles: Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Nope (2022). The novels, meanwhile, articulate our collective anxiety about global warming, gender and race relations, and a loss of trust in originality, truth, leaders, and institutions. In the terse titles The Bee Sting, Butter, and Yellowface the world feels compressed into a single, loaded word or phrase. The yellow jacket motif unites them: colourful and alluring on the shelf, yet signalling danger and the risk of a lethal heartbeat. Across these novels, the unmooring of climate time intersects with fractured family chronologies, as personal histories accumulate like toxic detritus.

In The Bee Sting (2023), Irish author Paul Murray’s Booker‑shortlisted novel takes its yellow cloak and its title from a deceptively buzzy and whimsical image. On the front cover, readers see the swirls and swoops of a bee’s flight path. The insect itself is poised to land, its sting hidden beneath gossamer wings, giving the jacket a glaze of honeyed sweetness. There is barely a hint of what is to come: a family’s slow unravelling, slick with national cruelties and unprocessed grief.

In The Bee Sting (2023), Irish author Paul Murray’s Booker‑shortlisted novel takes its yellow cloak and its title from a deceptively buzzy and whimsical image. On the front cover, readers see the swirls and swoops of a bee’s flight path. The insect itself is poised to land, its sting hidden beneath gossamer wings, giving the jacket a glaze of honeyed sweetness. There is barely a hint of what is to come: a family’s slow unravelling, slick with national cruelties and unprocessed grief.

Set in the early 2010s, the narrative orbits the Barnes family. Dickie Barnes is a car‑dealer turned doomsday prepper whose environmental sympathies collide with the capitalist ambition of his business. Over four long sections – focalized from the perspectives of the children Cass (age 17) and PJ (12), followed by those of their parents Imelda and her husband Dickie – the novel mines our current age of loneliness. Murray traces how the Celtic Tiger crash and climate grief warp domestic life in Ireland. Cass takes on a school geography project, which she does in collaboration with her father and which calculates the carbon emissions generated by his family car‑dealership business. The revelations from her research unsettle him and spur on dramatic changes in how he thinks about climate responsibility.

In the novel’s final part, also titled ‘Age of Loneliness’, Murray experiments with form. The narrative snaps into the second person, with a breathless tone and often unpunctuated sentences that mirror the overwhelming influx of news alerts and apocalyptic forecasts.

The Bee Sting shows that the novel can now confront environmental breakdown head‑on – a riposte to Amitav Ghosh’s claim in The Great Derangement that fiction has failed to apprehend the Anthropocene. In Murray’s rendition, anxieties are generational: should you bring children into the world to mend a brittle relationship? This question is heightened by the fact that the world itself is collapsing. Imelda’s suppression of sorrow over her first lover’s death, Dickie’s rejection of his own queer desire, and their children’s struggles with both alcoholism and a catfishing online ‘friend’ all gesture towards society’s broader unwillingness to face the fact that the political, social and environmental trouble is coming from inside the house. As PJ thinks at one point, ‘The past is literally still around […] a sky full of jet contrails’. Like pollution in our atmosphere or a bee sting in the blood, the family’s poisonous past seeps into the present, an accumulation of history that haunts every decision they make. In its open‑ended finale – where narrative momentum speeds up towards an inevitable conclusion – Murray’s yellow jacket pulses a warning. In the hive of modern life, family and environment prick each other relentlessly.

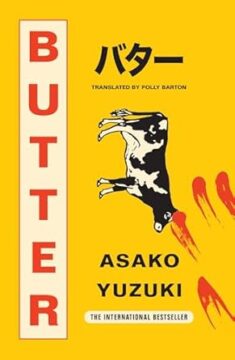

Butter by Asako Yuzuki, first published in 2017, was translated by Polly Barton from Japanese into English in 2024. The book joins other one-word, yellow-jacketed novels in hiding a sting in the tale. Its primary cover and silken title evoke warmth and comfort, but blink and the peril comes into focus. Butter’s domestic setting speaks of home cooking and comfort food but this papers over a lethal suspense. In Yuzuki’s thriller, a Tokyo journalist named Rika Machida befriends her interviewee Manako Kajii. Rika is writing a profile of Kajji, an overweight gourmet cook incarcerated for seducing lonely businessmen with her elaborate meals before allegedly killing them. Rika is desperate to get the scoop of how Kajji’s sumptuous feasts turn sinister. However, she soon finds her own taste buds and skinny body tantalized by the epicure’s love of food. By placing murder in the kitchen, Butter turns familiar homeliness into a hostile environment. In these pages, a family meal can be as dangerous as a hornet’s nest.

Butter by Asako Yuzuki, first published in 2017, was translated by Polly Barton from Japanese into English in 2024. The book joins other one-word, yellow-jacketed novels in hiding a sting in the tale. Its primary cover and silken title evoke warmth and comfort, but blink and the peril comes into focus. Butter’s domestic setting speaks of home cooking and comfort food but this papers over a lethal suspense. In Yuzuki’s thriller, a Tokyo journalist named Rika Machida befriends her interviewee Manako Kajii. Rika is writing a profile of Kajji, an overweight gourmet cook incarcerated for seducing lonely businessmen with her elaborate meals before allegedly killing them. Rika is desperate to get the scoop of how Kajji’s sumptuous feasts turn sinister. However, she soon finds her own taste buds and skinny body tantalized by the epicure’s love of food. By placing murder in the kitchen, Butter turns familiar homeliness into a hostile environment. In these pages, a family meal can be as dangerous as a hornet’s nest.

The novel discreetly embeds climate anxiety in its plotting. It opens during an intense heatwave that triggers a national butter shortage in Japan. This detail of a simple ingredient becoming scarce hints at ecological calamity even in a mystery about sexuality, scandal, and murder. The pressure cooker of inequality of resources and a burning planet thus frames the crime. Butter examines consumption and collapse turning into an appetite or even a craving for blood. Yuzuki shows our ordinary lives, relationships, and food supplies are fragile. By alluding to torrid weather, the dairy farming industry, and food insecurity, the book taps into apocalyptic concerns without losing its intimate focus.

These ideas melt into Butter’s core interest in women’s bodies and desires. Kajii’s lavish cooking is entwined with sexual power, for she is a femme fatale whose appetites seem to subvert social norms. Rika’s own role shifts from dispassionate investigator to full participant as she savours Kajii’s rich fare. Having gained weight enjoying Kajii’s recipes, Riki encounters the same vicious fat-shaming, much of it digitalized, that haunted the accused murderer. Japanese women are pressured not to take up space in just the way described in sociologist Nirmal Puwar’s Space Invaders. Kajji and, eventually, Rika refuse the thin and self-sacrificing female ideal. Yet Kajii also repeatedly expresses disdain for feminists and feminism, even confessing that she ‘loathe[s] women’. She has entered into a bargain with patriarchy, swapping a svelte figure for the more capacious but still binary Black Widow spider role of nurturing and killing. This undercuts any notion of her as a subversive character; she is marinated in misogyny and plays into the Madonna-whore dichotomy. Thus Yuzuki mobilizes culinary seduction as a way of probing sexuality. Cooking becomes a form of intimacy and control, and women’s appetite for food or autonomy is portrayed as both attractive and threatening. The novel challenges who gets to consume whom: Rika and Kajii’s relationship blurs lines between the reporter and the reported, the hunter and hunted, questioning conventional gender and sexual roles.

At the end of the narrative, Rika establishes an alternative household: an apartment she buys where her friends congregate, cooperate, and savour their food without imposing obligations on one another. This loose association or chosen family stands in contrast to traditionally unequal gender relations, suggesting forms of kinship, domesticity, and sociality not rooted in exploitation. Yuzuki may be gesturing here towards a more equitable, non-extractive polity, one that reimagines domestic and social bonds beyond sexist hierarchies.

At the end of the narrative, Rika establishes an alternative household: an apartment she buys where her friends congregate, cooperate, and savour their food without imposing obligations on one another. This loose association or chosen family stands in contrast to traditionally unequal gender relations, suggesting forms of kinship, domesticity, and sociality not rooted in exploitation. Yuzuki may be gesturing here towards a more equitable, non-extractive polity, one that reimagines domestic and social bonds beyond sexist hierarchies.

Butter’s eye-catching design is part of its takeaway. Sunny and appealing, the sunflower tint is marked with red streaks like blood splatter and even, in some editions, a vertical Friesian cow which stands or plummets headfirst down the page. One reader calls the cover paratext ‘arresting’, noting less favourably that the bold yellow jacket is smeared with bloody fingerprints. The buttery yellow cover is alluring bait that masks the novel’s horror, emblematic of the story’s heady brew of culinary delight and hidden menace. On one level, there’s the literal consumption of dairy and meat, which requires the suffering and slaughter of animals to satisfy lactose-drenched, fleshy cravings. On another level, there’s the metaphorical consumption of crime stories, where the public ‘feeds’ on sensationalist media coverage of murder (like the story of Kajii as a female serial killer in Butter). The novel questions how appetites – whether for food or for lurid tabloid stories – are exploitative and driven by desire, with violence (slaughter, murder) as their covert cost.

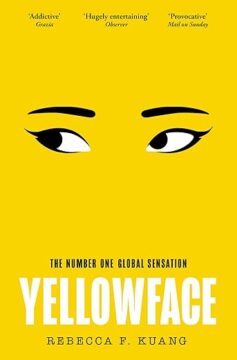

Finally, the single-word title and blazing jacket of Yellowface (2023) tag it as another cautionary tale. Rebecca Kuang’s novel, like Yuzuki’s, is fascinated by women’s ambition and sexuality. Its young Chinese-American author Rebecca Kuang extends this interest in gender and the broader ‘yellowjackets’ trend into the realm of the Yellow Peril, with Orientalism, racism, and cultural appropriation taking centre stage. Questions of race, among other identity components, colour the perception and reception of this novel and the fictional ones it conjures up.

Finally, the single-word title and blazing jacket of Yellowface (2023) tag it as another cautionary tale. Rebecca Kuang’s novel, like Yuzuki’s, is fascinated by women’s ambition and sexuality. Its young Chinese-American author Rebecca Kuang extends this interest in gender and the broader ‘yellowjackets’ trend into the realm of the Yellow Peril, with Orientalism, racism, and cultural appropriation taking centre stage. Questions of race, among other identity components, colour the perception and reception of this novel and the fictional ones it conjures up.

Kuang’s graphics lean into this: the cover is a golden field pierced by monochrome cartoonish eyes. From the sunflower-yellow backdrop, these eyes peer out in an accusatory yet beguiling stare. Yellow book covers are usually linked to optimism, but once again the obverse is aposematism, conspicuous colouration to ward off danger. The minimal ‘face’ on Kuang’s book suggests a mask, optics, and an empty avatar – fitting images for a story about stolen identity and curated online personas. Below, the title Yellowface appears in blunt white capital letters, suggesting urgency and even bald-faced audacity.

The title ‘Yellowface’ elicits disguises and the masquerade. A leading back blurb even snarls, ‘This is one hell of a story. It’s just not hers to tell’, in an overt warning that culture wars lie ahead. By invoking the racist theatrical practice of yellowface, when non-Asian actors pose as Asian, the novel flags up that a crisis of identity and authorship lurks at the heart of its satire. This one-word title does other symbolic work, figuratively announcing the novel’s theme of ventriloquizing another’s voice. The cover thus prefigures the novel’s tension. Beneath the glamour of yellow lies the darkness of cultural theft.

Kuang dramatizes this theft through the first-person narrative of June Song Hayward. Apparently sunny June has a dark side. She is a jealous white writer, who snatches her dying friend Athena Liu’s unpublished manuscript, edits it hard, and passes it off as her own. Kuang’s bestseller about the combustible mix of racial tensions and jealousy among authors proceeds to offer a curious look into what goes into manufacturing a star in the global literary marketplace. The identity of the author becomes a palimpsest upon which corporations and authors themselves add layers of self-promotion and canonization using conventional media and social networks. Her publishers encourage waspy June to reinvent herself as Juniper Song, taking ethnically ambiguous headshots that mean she could be misinterpreted as having Chinese heritage.

Kuang’s novel turns the collaborative nature of authorship into crime. Duplicitous June is at once artist, editor, influencer, and imposter. In this way, Yellowface interrogates intellectual property and originality. June’s act of ‘borrowing’ Athena’s story is cast as transgressive. Yet, as the novel implicitly observes, creativity is often born out of imitation and co-authorship, all the more so as AI makes inroads into the way texts are imagined and executed. June indeed learnt from Athena and reworking the draft is her own craft.

What’s more, the fictional Chinese-American author Athena Liu herself was far from a perfect victim, having regularly pilfered stories from members of the Chinese community she encountered. Through Athena, the author critiques the way she, Kuang, has had to sell her Chinese identity (i.e. a form of yellowface) in the literary marketplace. She also mocks how her own ‘Chineseness’ has been promoted to consumers by publishers, the media, and the literary industrial complex. The fictional character, like the author herself, is a young, beautiful, award-winning Chinese-American novelist. The novel strongly implies that Athena, despite her success, was not free to write whatever she wished. Her identity was heavily leveraged by powerful publishing players. June Hayward, the jealous narrator, frequently observes this, though usually through biased and racist takes like this:

What’s more, the fictional Chinese-American author Athena Liu herself was far from a perfect victim, having regularly pilfered stories from members of the Chinese community she encountered. Through Athena, the author critiques the way she, Kuang, has had to sell her Chinese identity (i.e. a form of yellowface) in the literary marketplace. She also mocks how her own ‘Chineseness’ has been promoted to consumers by publishers, the media, and the literary industrial complex. The fictional character, like the author herself, is a young, beautiful, award-winning Chinese-American novelist. The novel strongly implies that Athena, despite her success, was not free to write whatever she wished. Her identity was heavily leveraged by powerful publishing players. June Hayward, the jealous narrator, frequently observes this, though usually through biased and racist takes like this:

Publishing picks a winner – someone attractive enough, someone cool and young and, oh, we’re all thinking it, let’s just say it, ‘diverse’ enough – and lavishes all its money and resources on them. It’s so fucking arbitrary. Or perhaps not arbitrary, but it hinges on factors that have nothing to do with the strength of one’s prose. Athena – a beautiful, Yale-educated, international, ambiguously queer woman of colour – has been chosen by the Powers That Be.

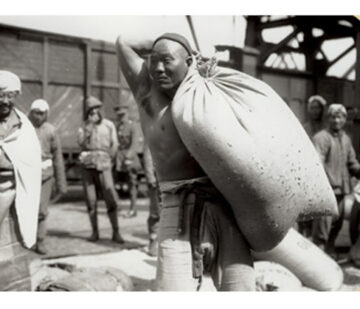

While June frames this as Athena’s unearned privilege, the novel also reveals the flip side: this selection comes with expectations. Athena is pushed to write stories that fit a certain marketable ‘Asian-American experience’, often focusing on historical trauma or immigrant narratives. This is evident in the manuscript June steals, The Last Front, which is about conscripted Chinese labourers during the First World War. While it is Athena’s original work, the novel indicates that her path to success was paved by relying on this kind of story, which then became her brand.

Candice, an Asian-American publisher, launches a scathing verbal attack on June, revealing the compromises she believes Athena had to make. During this confrontation, Candice reveals the immense pressure Athena was under to perform her identity and write narratives that catered to the publishing industry’s preconceived notions of multicultural literature. Candice’s words serve as a crucial voice of truth, tearing down June’s self-serving narrative about Athena’s ‘easy’ success:

Candice, an Asian-American publisher, launches a scathing verbal attack on June, revealing the compromises she believes Athena had to make. During this confrontation, Candice reveals the immense pressure Athena was under to perform her identity and write narratives that catered to the publishing industry’s preconceived notions of multicultural literature. Candice’s words serve as a crucial voice of truth, tearing down June’s self-serving narrative about Athena’s ‘easy’ success:

Do you know how much shit Athena got from this industry? […] They marked her as their token, exotic Asian girl. […] Racial trauma sells, right? They treated her like a museum object. That was her marketing point. Being a Chinese tragedy.

Candice also implies that Athena’s success came at the cost of her artistic integrity, forcing her to tailor her work to fit market demands: ‘She knew the rules. She fucking milked it for all it was worth’. Candice’s confrontation leaves June (and the reader) with an unflinching picture of the limitations and expectations placed upon Athena.

Thus, ‘yellowface’ refers to Athena as well as June, and the original novelist’s own performance in the international book trade. She embodies the ‘model minority’ writer who, in a different way to June, also wears a ‘face’ for the industry, conforming to its demands for a certain type of ethnic narrative. This highlights Kuang’s complex critique. Yellowface is not just about white authors stealing marginalized voices, but concerns the structural demands that force marginalized authors to present their identities in ways that feel increasingly inauthentic and limiting.

Despite all this complexity, public opinion beatifies Athena and judges June harshly, dehumanizing both writers in the process. Waves of aggression and shaming flood June’s social media daily. She becomes Twitter’s latest sacrificial lamb – or, to extend our guiding hymenopterous metaphor, prey caught in the hive mind’s pile-on. June’s plight is reminiscent of the backlash faced by Hilaria Baldwin, who was born Hillary Hayward-Thomas and thus shared part of her surname with the fictional writer. In December 2020, Baldwin was exposed for profiting by a years-long impersonation of a Spanish woman from Mallorca when she is in fact from Boston.

Race compounds the crisis, however, making June’s grift perhaps more reminiscent of the deception of Rachel Dolezal, the white woman who pretended to be Black, than Baldwin’s. June’s theft is not just of any manuscript but of an Asian-American story. By stepping into Athena’s identity and adopting the publisher’s manipulative pen name, June dons a ‘yellow face’. The novel’s suspense pivots on whether the charade will explode in this visage. The outcome is psychological jeopardy: June loses her grip on who she is, and readers see how thin the line is between one creative self and another.

Yellowface’s paratexts – its title, colour, and design – all signal a fraught fake identity. The sunshine-yellow cover lures the eye, but its message is stark. Kuang’s novel unfolds this visual cue into a drama of race, literary hoax, and plagiarism. Threat and transformation entwine as authorship is shown to be unstable and entangled. As Athena’s black lashes on yellow warn, the greatest danger here is not murder but the erasure and usurpation of a writer’s life – a crisis of originality itself.

Yellowface’s paratexts – its title, colour, and design – all signal a fraught fake identity. The sunshine-yellow cover lures the eye, but its message is stark. Kuang’s novel unfolds this visual cue into a drama of race, literary hoax, and plagiarism. Threat and transformation entwine as authorship is shown to be unstable and entangled. As Athena’s black lashes on yellow warn, the greatest danger here is not murder but the erasure and usurpation of a writer’s life – a crisis of originality itself.

Taken together, The Bee Sting, Butter, and Yellowface show that sizzling yellow book jackets lure and alert readers of mid-2020s fiction. Each novel sports its curt title like a neon sign, beckoning in consumers while hinting at embedded menace. Murray’s Irish intrigue unfurls familial pain in the context of financial and climate disaster. Yuzuki’s Tokyo tale stirs ecological dread into a voluptuary veneer of butter. Finally Kuang’s publishing pastiche exposes how self-fashioning and ambition can turn so toxic they should come with a warning label. These yellowjackets embody fiction’s new admonitory impulse, reminding us that in art as in nature, the brightest colours often conceal the sharpest threats.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.