by Michael Liss

“[T]o hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions….” —Lillian Hellman, Letter to the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), May 19, 1952

She wouldn’t do it. Despite seeing her reputation trashed, her income from her work disappear, her companion Dashiell Hammett (the creator of Sam Spade) sent to prison, Lillian Hellman wouldn’t name names. She’d testify about herself, but she wouldn’t sell out friends and acquaintances just for a little leniency.

There are moments in our history when, despite being the greatest democracy in the history of the world, a type of madness descends on us. We lose our bearings, our guardrails, our principles and even our dignity. We become consumed with the thought that our very existence is at risk, and those bearings, guardrails, principles and dignity become luxuries we can no longer afford. A communal paranoid state of mind exists, and, until the fever breaks, we do a lot of damage to ourselves and our institutions.

Most of the time, we can weather it, in part because our government and our laws create a framework for restraint. Disputes get resolved through the ballot box, the legislative process, and, if necessary, the courts. As long as the fight is basically a fair one, it would be like a World Series—you might eat your heart out if your guys lose, but, to cite the pre-1955 Brooklyn Dodgers, “there’s always next year” and, in a fair fight, historically at least, there always has been.

Fair doesn’t always happen, or at least it doesn’t happen right away. Human nature, and circumstance get in the way. When we are in one of those Madness Moments, and the government is dominated by people willing to make maximalist use of power, whether it legally exists or not, then the dynamic changes radically. It isn’t any longer “I won, I will take this” but “I won, I will take this from you” or even “I won, I will take everything from you, including your dignity.”

Such a time came for Lillian Hellman, for Dashiell Hammett, for their friends, for the greater writing and artistic community, for open activists and even those regular folks who might have just ended up on a subscription list, or had given a few bucks to some do-gooder group, or even gone to the wrong dinner. Their government, caught up in the mania called the Red Scare and McCarthyism, flexing itself well beyond what Madison or Jefferson would have thought were its boundaries, searched their records, summoned them, interviewed them, intimidated them, had them fired, and in some cases jailed them.

There were big moments, like October 1947’s “Hollywood Ten” hearing, when 10 motion-picture producers, directors, and screenwriters were dragged in before HUAC, sent to jail for refusing to testify, and then Blacklisted. Stunts like this made for great political theatre—the stern, self-righteous pols, contemptuous of basic civil liberties, eyes always searching for the nearest camera or microphone, indignantly questioning/hectoring/threatening.

Big moments, but many more small ones, the less famous, the thousands of ordinary people, first in government (where the State Department was purged) and then in private industry, where, if you were on the wrong list, particularly the “Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations” (AGLOSO), you could find yourself unemployable. That’s the less-known, darker secret of the era—the number of everyday victims.

Hellman’s time in the sun came on May 21, 1952, just three days after her letter, but more than five years since the Frankenstein Monster had lurched to life. Wearing her “Balmain Testify Dress” and accompanied by her lawyer Joseph Rauh, she appeared before the Committee and spoke about herself, but stuck to her guns about not naming names. Hellman recounts the experience in her 1976 book Scoundrel Time with kaleidoscopic memory that is one part skepticism, one part outrage, one sheer terror, and one late-in-the-hearing providential moment: a big voice from the press gallery that said “Thank God somebody had the guts to do it.” Shortly after that, just one hour and seven minutes from when it began, it was over. The Committee apparently had had enough and so had Hellman. She left as fast as she could, accompanied by Raugh’s assistant Daniel Pollitt, and the pair beat it to a local restaurant, where they downed multiple Scotches.

The whole country could have used multiple Scotches. How did we ever get into such a mess, looking for red monsters under people’s beds?

To an extent, it was a bipartisan effort. Garry Wills, writing the introduction to Scoundrel Time, makes the excellent point that McCarthyism didn’t start with McCarthy—in fact, it could be more accurately be called “Trumanism.” On March 21, 1947, Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9835, which required that all federal civil service employees be screened for “loyalty.” How does one show disloyalty? In part, by being a member of, affiliated with, or “sympathetic” to (whatever that means) an organization that is “totalitarian, Fascist, Communist or subversive.” Who determines whether an association meets those criteria, or supports the “forceful denial of constitutional rights to other persons,” or wants to “alter the form of Government of the United States by unconstitutional means?” That would be the Attorney General, Tom Clark. Truman, Clark, and J. Edgar Hoover empowered HUAC and gave them The List, and the Committee went from there. Communists, it seemed, were everywhere.

Why did they do this? Hoover’s motives are certainly open to question—the FBI’s investigatory powers, especially for domestic surveillance, grew enormously during the war, and Hoover wanted to keep it that way in peacetime. Truman is a different story, maybe one not entirely admirable. It’s probably not fair to question Truman’s bona fides on anti-Communism. He, through the Truman Doctrine, made it central to his foreign policy. But it is fair to ask if the pervasiveness of his domestic anti-Communism policies weren’t at least somewhat motivated by politics. In 1946, for the first time in 16 years, the GOP took back the House, and the result cast doubt on Truman’s chances of being re-elected in 1948. Being uber-firm on Communism helped (it was thought) with the public at large.

Let’s take that as a jumping-off point. America had never particularly loved Communists and were more than a little wary of Socialists—not just for their ideology, but because many immigrants from Europe brought their preferences—and those preferences were not always for American-style Capitalism. The animus intensified when Stalin and Hitler’s representatives signed the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact in August 1939, just a few days before Hitler’s September 1, 1939 invasion of Poland. Operation Barbarossa in June of 1941 brought that to an abrupt end, and Russia now became “Our brave Russian Allies,” meaning, it was OK, sort of, to speak kindly of them.

Not really. We never liked the alliance all that much, especially when the Soviets promptly began acting in their self-interest. In February 1945, the “Big Three” met at Yalta, where Russian tactical positions on the ground caused Churchill and (a very sick) FDR to make significant territorial concessions. Truman’s one and only Conference, at Potsdam, basically achieved little—Stalin already had most of what he wanted.

Then, we dropped the bomb(s) and the world changed again. Suddenly, the war was all over, and there was a new reality with new competition: to quote John F. Kennedy at his Inaugural Address 15 years later, the torch that had been passed to (his) generation of Americans was “tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace.” That “hard and bitter peace”? Cold War.

In 1946/47, two things could be true at the same time: The first, per Wills, “[b]y virtue of our brains and effort, we made ourselves the most formidable industrial and military power in the history of the world.” The second: America was the world’s only superpower, but it had a super-villain as its perpetual rival. That super-villain would only grow stronger with its acquisition of the A-Bomb, and the threat even greater when China “went Red” in 1949.

Wills makes an interesting point: “We achieved that most refined of pleasures, a virtuous hate.” A virtuous hate unleashes you to do things that would otherwise be morally troubling. How about an idea that “hides behind an otherwise law-abiding and unmenacing exterior”? In Wills’ words: “Then one must steel oneself against all normal amenities and personal attraction. Then one launches a crusade—to be followed by an inquisition.”

Wills is unsparing with what occurred in this inquisition. The Committee brought in “Friendly Witnesses” like Ronald Reagan and Ayn Rand, and unfriendly ones—those who directly challenged their authority, like acclaimed screenwriter Dalton Trumbo and the rest of the Hollywood Ten. It was a mess—botched hearings, fragmented or convenient memories, sometimes craven witnesses (Wills’ recounting of the testimony of the actor Robert Taylor leaves you somewhere between cringing and laughing), and, ultimately, ruined lives.

As in any time when character is tested, some responded better than others. Occasionally, there was the naming of names by people who, out of fear or selfishness, turn on their friends. Multiple Oscar-winner Elia Kazan, who directed Gentleman’s Agreement and A Streetcar Named Desire, chose this path—and was sensitive/defensive enough about it to take out an explanatory advertisement in The New York Times.

Some profited from trafficking in gossip. The columnists Hedda Hopper and George Sokolsky both spread around new names for the Committee to investigate and served as den-mothers for those actors who wanted to show their patriotism and perhaps receive forbearance. With this, they widened their audience and enhanced their influence even more.

In the end, McCarthyism burned itself out, like McCarthy himself, but not before incalculable damage. The issue really wasn’t how awful the Soviets were—they were quite bad. It was more how basic Constitutional rights, of free speech, of assembly, even of thought, were tossed aside in an endless quest for “loyalty.”

There is something in human nature that brings us to points like these. Our collective limbic system senses danger, it rapidly pumps out a big dose of adrenaline, and each of us responds consistent with our nature. Some are heroic, others just hope it all passes before anyone comes to their door. Some embrace authoritarianism out of ambition, or a desire to profit, monetarily or politically, or even as a matter of temperament. It’s folly to assume that, just because as a nation we look back to Independence and Constitutionality as a model of civic virtue, we all embrace those liberties. Many do not, at least not for others.

Wills has an acute observation: “But ours was the first of the modern ideological countries, born of revolutionary doctrine, and it has maintained a belief that return to doctrinal purity is the secret of national strength for us.” If we doubt, if we question, any portion of the prevailing doctrine, we are somehow relegated to a second class of citizens—the non-pure that “can be harassed, spied on, forced to register, deprived of governmental jobs and other kinds of work.”

After all, “How are we to know what others think about the doctrines of Americanism unless we investigate their thoughts, make them profess their loyalty, train children up in the government’s orthodoxy”?

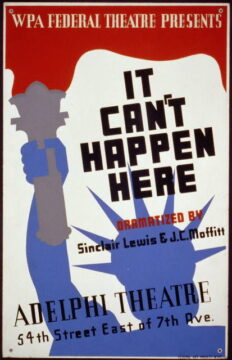

Wills wrote his introduction a half century ago, but that last question retains its iciness. This country is an idea—an idea and an ideal. A break away from monarchy, a celebration and codification of individual liberties, and a rejection of any top-down government orthodoxy that demands we take anything less than the freedoms promised us. But an idea and an ideal both need defenders, people willing to step up, take personal risk, show the way for others. It has always been this way in America—because what we have is precious, too many try to take it away from us, and, often, too few are willing to be ardent defenders. Sinclair Lewis had been right. It can happen here, especially when a government can declare an emergency and use it as a pretext for escalating authoritarianism.

Lillian Hellman understood that. She sat in the witness chair, held herself together in a sea of hostility, and kept the faith with her principles and her conscience.

We ought to draw some strength from that, and some courage.

Special thanks to Mike Posever, who shared several insights.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.