by Andrea Scrima

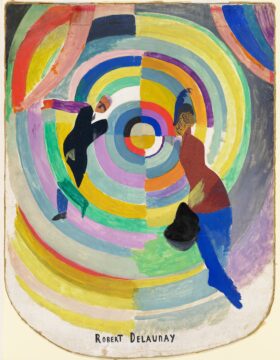

Here are Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV of this project. Images from the exhibition LOOPY LOONIES at Kunsthaus Graz, Austria, can be seen here.

15. QUO VADIS?

(Where Are You Going?)

As children, we rely on the help of our caregivers and our innate capacity to learn. And we learn quickly: to protest against the things we do not like, to demand the things we want, to shamelessly push aside siblings, schoolmates, playground companions to grab whatever prize is at stake. Or have you forgotten how ruthless childhood can be? Only later do we learn to share; although adulthood teaches us better manners, these basic instincts remain.

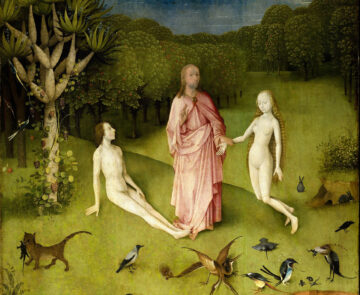

Saint Peter, encountering a resurrected Christ along the Appian Way, asks “whither goest thou?” Jesus responds that if Peter deserts his people, He will continue on to Rome to be crucified a second time, whereupon Peter takes heart and returns to meet his fate. In reminding us to reassess our decisions, the question Quo Vadis? urges us to come clean about the rationalizations we present to the world and to admit to ourselves our shame and our cowardice. Yet it also contains another meaning: that we are knowingly exposing ourselves to certain punishment. If we return to Rome, it is to face a danger we may have only just managed to escape. But what do we achieve when we put our lives on the line, and who will we help in doing so?

Behind the question lies another question. Peter is running not toward anything but away from persecution and, ultimately, his own execution—but he is abandoning, in the process, his faith, his followers, and everything he has previously stood for. What is a life worth? And what is worth giving one’s life for? To ask this today sounds like madness; it is the language of fanatics, of zealots, of the mentally unstable. We live in a world of moral relativism in which taking an ethical stance is regarded—and scoffed at—as a pose, a bid for attention. We convince ourselves that the truth is both to complex and too subtle to warrant reckless, drastic acts; that the emotions we feel—the disgust, the fear, the outrage, the self-loathing—are too roughly hewn to be mistaken for the demands of the conscience, which we imagine as something abstract and pure. Our awe at the spectacle of self-sacrifice turns to repulsion; unable to imagine it as a decision a person may arrive at through an act of logical reasoning, we view it as something foreign and grotesque. Quo vadis? We are called upon to consider the values we profess and ask ourselves whether we actually practice them. We mistake our equivocations for wisdom, our compromises for judiciousness. Yet behind them lie our most basic instincts, first and foremost our will to survive—stripped now of the innocence of childhood, because we have lived long enough to see the consequences of our inaction. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

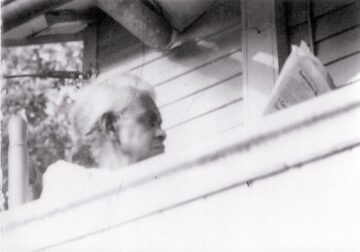

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.