by Richard Farr

That year on Oahu I was renting half a small ranch house in Kahala. Typically, I would greet the evening with a glass of wine next to the pool, enjoying the pretense that I’d joined the idle rich. Not that day. As the sun went down I sat at my desk in a pair of swim trunks, trying to scratch out some notes about what had happened. I had a folded handkerchief between my wrist and the page. Each time my pen made contact with the legal pad a dozen filaments grew out from its point, embedding themselves in the paper like the roots of epiphytes. The air still had the density and turbulence of a simmering seafood bisque. I kept brushing my shoulders and arms, mistaking the sweat for flies.

*

At three or four in the morning, in the middle of a banal anxiety dream, I was pecked awake by rain. A dog barked, then at the same moment both it and the rain fell silent. For days we’d been in the arms of this thundery air, like children clutched to the bosom of a big moist relative.

The Civil Defense sirens, high on their utility poles, went off at 5:34 a.m. A single, minute-long blast, during which I tried to hold in my mind all the hundreds of thousands of people who were, like me, hoping the sound would go away and then rubbing their eyes and groping for the radio.

“ — why exactly everyone has been woken up by that thing?”

“Yes, Barry. That’s the Civil Defense warning siren, Barry. According to the Weather Office, the storm has tacked north and the tropical storm warning has been upgraded to a hurricane warning.”

The day before, this storm had been far to the south over the empty Pacific, mooching and loitering and chewing the water like a grazing bull. Powerful, but indifferent. Now it had spotted us, lifted its head, and changed course. It was bearing down, eyes sharp, lazily picking up speed.

I went into the shared kitchen to make coffee but the two women who rented the other half of the house already had the pot on. They were talking over the things you were supposed to do or have done, the things we and everyone else had not done.

“We need candles. Spare batteries for the radio.”

“Where’s that big yellow flashlight?”

“What about the windows?”

“Fill this with water.”

“Bread. We should get more bread. And canned food. Soup. Whatever.”

I volunteered to go to the supermarket. Lines of people were trailing from the doors like streamers of cloth from a clenched fist. It was raining again, and in the parking lot one man was shouting and gesticulating because someone had backed into his car. People were buying six-packs of duct tape, barbecue brickettes, ten-pound cans of pork and beans. I wanted ice. They were out of ice.

“Excuse me,” someone said to a man behind me, “is this the express line?”

“Lady, believe me, there is no express line.”

Hidden in all the shoving and anxiety there was a kind of delight. We had been singled out, noticed, made special. Instead of going to work, we were spending too much on stuff we probably didn’t need. It had an aspect of ritual, as if we were all getting ready to go on a date with a charismatic stranger.

For the next few hours the to-do list took over. Get the car under cover. Put big Xs of duct tape on the windows. Help the neighbor find her cat. Nail blankets over the taped windows. Throw the pool furniture into the pool. (Weeks earlier a man preparing for Hurricane Andrew in Florida was pictured doing just this. I thought: that’s funny, but I suppose it’s what you do. It was what we did.)

Finally, cook while there’s still power. I put sweet potatoes in to bake and made a huge cauldron of ratatouille, boiling the juices in a separate pan to make a viscous sweet liquor, congratulating myself in advance on how good it would taste even if we had to eat it cold.

The wind was rising, but it didn’t feel like anything dramatic. I decided to walk to the water, take a look at the surf before things got serious. But as I was about to leave there was an announcement:

“We have — we have — just hang on a minute there folks. We have an official message coming over the emergency broadcast system any second. This is an official message from the Civil Defense Network. Just stay tuned there. OK, we have seven seconds here before the message, five, four, three, two, here it is.”

Barry was getting louder and louder, faster and faster, a cheerleader egging on the crowd. The civil defense official was hard to follow at first because the contrast in diction was so great. He spoke with slow deliberation. There was something eerily detached about his voice, as he was looking down on our destruction from a great height. It was a tone I associated with pre-recorded messages to doomed populations in movies about Armageddon. It was as if the bomb was about to drop, and these words had to be loved despite their coldness because they had been prepared so thoughtfully in advance and were the last human voice we would ever hear.

I half expected the radio to crackle and go dead, but instead he said something I failed to follow about evacuating tsunami inundation areas. Barry came back on and clarified the point, his own delivery a little slower as if he was trying for the gravitas of the civil defense man:

“Let’s be clear that this is not, repeat not, a tsunami warning. Hurricanes and tsunamis are not in any way associated. But they are expecting some mighty big surf. We have a high tide scheduled for four o’clock, and that high tide is just exactly when the brunt of this hurricane is expected to hit. So if you are in those areas you should certainly leave your homes and go to a shelter.”

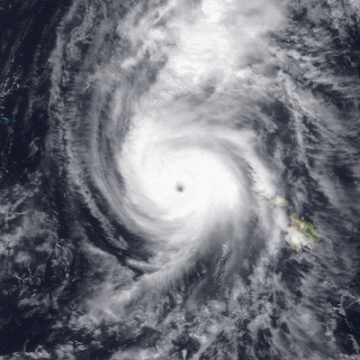

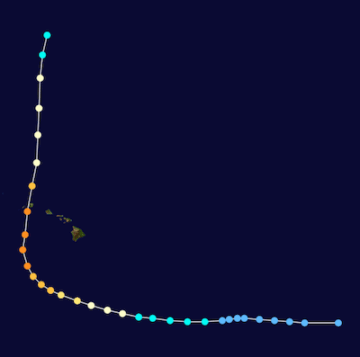

Hurricane Iniki, it was called. It seemed unwise to use a name at all, but especially something that sounded like a diminutive — treating a wild animal of immense size as if it were a pet. It made you worry that the people at the weather service did not grasp what they were dealing with. That they had misunderstood not only the storm’s size but also its seductiveness, its charm, its malevolence.

The eye was still far to the south, moving towards us at seventeen miles per hour. At its core, they said, the air was being goaded to 150 miles per hour, or 170. The weather people said that on its earlier course the eye would have missed us, but now we could be facing a direct hit.

Outside there was still no sign of it, just a crumpled sky the color of oatmeal. There was almost nobody about, just a couple of kids on bicycles cruising the streets very slowly as if looking for something. Down at the beach, palms were brawling with one another and spitting coconuts onto the sand like teeth. The waves were big on the reefs — irregular, beefy, bullying waves, shoving and chuckling and holding each other down. But that was two hundred yards out and the shore was protected. The wind was kicking up some whitecaps, but at my feet there was only a light foamy wash with the usual confetti of wood and garbage.

Back at the house there was nothing left to do except sit over coffee and feel the tension rising. A gust picked up the sliding doors and shook them for a few seconds. I wondered whether it would take half a minute of that, or more, before the glass croaked a final apology and the monster came into the living room. Barry said:

“Folks, it’s no longer a question of whether we are going to get slammed by a grade four hurricane. It is a question of when.”

You could hear him grinning. He sounded like a man who knows that his flirtation has been successful and that the woman of his dreams is about to embrace him. But as we waited for Iniki’s cathartic rage to break over us, he introduced a weather expert, an academic. He had been brought into the station to anoint us with the oil of science. He said the wrong thing.

“The storm is almost as close to us as it’s coming. It is currently about one twenty miles to the south east, moving west-by-north-west.”

“But this new shift?”

“Well, yes, there has been a shift. And in this new direction it will not hit us.”

“Straighten us out here, Professor. Are you — are you saying that this is the worst it’s going to get?”

You could tell that Barry had scarcely dared to ask the question, that only in formulating it had he grasped the answer.

“Yes, Barry, that’s right. The storm is accelerating still, actually now traveling at more than 20 mph, which is very fast, but the good side of this is that it is extremely compact.”

“What about the winds, these very high winds?”

“Yes, indeed. But just as the storm center is extremely powerful, the level of activity drops off from the center very quickly. These strong winds, we are only talking about, oh, thirty to forty miles from the center. So here we are a long way out, already out of it one might almost say.”

For a few minutes after this there was confusion. The expert disappeared. Suddenly unsure of themselves, Barry and someone else in the studio started to reminisce:

“Do you remember when we were up in Kauai, what, ten years ago?”

“Ten years. Almost to the month.”

“And those winds were only half this speed.”

“That’s right. Sixty, seventy miles per hour and that did some terrible damage. Right now they look set to be hit by gusts of one hundred sixty.”

“These systems are very unpredictable. This guy could be going one way, could pass us by, then turn right around.”

“Turn right around and come back.”

“Right.”

A man called the station to complain that the authorities and the media had overstated the danger. He tried to point out inconsistencies in the reporting. The direct hit on Oahu, he seemed to be suggesting, had been nothing more than an irresistibly good story.

The punishment was relentless. Once the announcers saw that their new caller could be portrayed as a complainer, as someone insufficiently grateful to those working for his protection, they had the perfect vehicle for everyone’s illicit and inadmissible anger that destruction and its entertainments had jilted them. For the rest of the day he was “that guy who called.” “That guy” became a symbol, a myth, the person who is too selfish and stupid to understand what others are doing for him. Callers loved it; they joined in:

“I’d like to say to that guy who called that if he thinks it was a false alarm he should get his butt out our way. We have real strong winds here, and — ”

“That guy, jeez, it would be some kinda poetic justice or something if he got blown from here to Australia.”

Soon there were different stupid people to shake our collective head at. There was a report about a small fishing boat trying to make landfall. They had asked for a helicopter to take them off. They were breaking up. Why was anybody out there anyway? Nobody should be in a boat.

“Maybe they didn’t hear the sirens! Maybe they didn’t listen to the radio!”

“Maybe they just didn’t get the message, Barry.”

“Oh yes, there’s always that ten per cent doesn’t get the message.”

A man called in from the windward side of the island and announced that it was “serene.” Another caller, a woman, countered at once: it was “howlin’ where we are, real rough.”

“Ma’am,” Barry said, “the guy who says its serene is probably just down the road from you. That’s the way it is. Or maybe he comes from someplace where sixty mile an hour gusts are nothing, to him ten inches of rain is a shower. It’s relative. To you it’s a storm. It’s all relative. Everything’s relative.”

You could tell Barry was on her side. He wanted to say that the other caller was an asshole for saying that it was serene, whether it was serene or not.

More and more attention was turned to Kauai, where the storm had already made landfall. If we could not have our own brush with eternity, we would have it vicariously. But that proved difficult.

“All communication with Kauai has been out for more than an hour at this time. The eye of Hurricane Iniki is now passing right over the island.”

They kept trying to keep up the tension, but it was no use. For eight hours we had been worshipping a great and terrible power, thrilled by the prospect of our own abasement. Now suddenly there was nothing to offer but the news that it had not found us interesting enough and was paying attention to someone else. There would be no more adrenaline, no more living bravely at the edge of destruction, only the prospect of putting away our unused supplies, embarrassed and sheepish at the memory of our own arousal.

The announcement that Iniki’s eye was clear of Kauai’s north coast seemed to put away the present tense. The hurricane had gone. It was something to recall. A couple of times they said things like:

“The hurricane warning has been downgraded to a tropical storm warning folks, but a tropical storm ain’t nothin’ to mess with, let’s be totally straight about that.”

It wasn’t convincing. We had been told to expect a hurricane. Instead we had been brushed by its skirts, flirted with, ditched.

*

In the gathering dusk people are moving about on the streets. There are no trees down, no destruction — everything looks as it did in the uncertain light of six o’clock, except that the yellow pool furniture is still lying scattered in the water, chairs on their sides, like the handiwork of an aquatic terrorist.

Early reports from Kauai are confused, a message filled with the static of ignorance, but it sounds bad. One house in five destroyed, half the remainder badly damaged. No power. Few roads passable and a couple washed away. They have had their hurricane, and they will not want another one to visit for a long time.

It’s different here. People are removing tape from their windows. There is a wistful look in their eyes.

The ratatouille is delicious.

We are still waiting.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.