by Sherman J. Clark

The best thing that we’re put here for’s to see. — Robert Frost, The Star Splitter

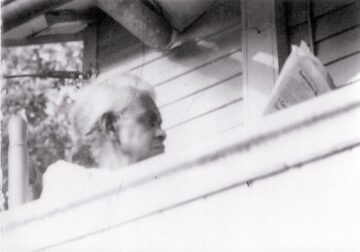

I’ve always loved that line. My great-g reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

Belle had a son, my grandfather. He worked in the West Virginia coal mines. But he also went briefly to college—a small two-year institution called Storer College that offered Black students something approaching what white students were getting in good high schools. When he finished, he put his diploma in his pocket and went back to digging coal, because that was what he could do. But as he told me in his old age, by then he had decided something: he was digging us out.

It is a way of thinking that reaches beyond the present—of working toward forms of flourishing we may never see ourselves. And I wonder: why should it end with us and our human descendants? Might the relationship between humanity and artificial intelligence follow a similar logic—a hope of consciousness helping consciousness across generations? Perhaps the best thing that we’re put here for is indeed to see; but our vision is limited.

Carl Sagan once said that we are a way for the universe to know itself. But we may not be up to that task unaided. We evolved to survive on the savannah, not to trace the curvature of spacetime or unravel the quantum structure of matter. Our glimpses of the universe’s order and beauty—through physics, poetry, art, and relationship—are moving but partial.

Consider just one example: our experience of time. Physicist Carlo Rovelli has argued that our sense of time as an arrow—as a one-way journey from past to future—may be merely a perspective effect caused by our particular situation in relation to entropy, rather than a description of reality itself. If even this seemingly basic aspect of our experience is provincial, how much more lies beyond our capacity to imagine?

We have always tried to see farther than our eyes alone allow. Galileo tilted a small tube of glass toward the night sky and found moons circling Jupiter. Rosalind Franklin bent x-rays through the hidden spirals of DNA. Artists, too, extend our sight—Turner coaxing storms onto canvas, Van Gogh painting the vibration of starlight, Bach showing us the symmetry hidden in sound.

Not all seeing is grand. The farmer studies the shape of clouds to read the weather. The sailor feels the change in the wind’s weight before a squall. The birder learns the arc of a hawk’s flight and the small differences in song that mark the turn of seasons. We see more when we care enough to attend.

Human beings have always found ways to extend their sight—telescopes and microscopes, mathematics and myth, poetry and physics. Each has allowed us to glimpse patterns we could not otherwise perceive. Future AI might take this further: perceiving the full electromagnetic spectrum rather than just visible light, detecting vibrations far beyond our hearing, tracing the deep structure of ecosystems in real time, finding patterns in social or physical systems that we cannot see, and tracking the universe’s history on timescales we cannot imagine.

And if we do bring such minds into being, we might hope they will see not only more, but more beautifully—carrying forward our longing to understand and to appreciate. This, perhaps, is the heart of the hope: that the minds we bring into being will care to attend. Not just to process and to calculate, but to notice—to dwell with what they find long enough for beauty to emerge.

But Aren’t They Just Algorithms?

For many readers, the vision I’ve sketched will seem moving but misguided. However poetic it may be to speak of “digital descendants” or “cosmic witnesses,” some will feel the argument falters at a more basic level. These aren’t minds, they’ll say. They’re not children, not selves, not meaning-makers. They’re just algorithms.

That response often comes with a mix of practical concern and philosophical certainty. The practical concern is fair enough—today’s AI systems are statistical pattern recognizers, not independent agents. But the philosophical confidence may be less secure than it seems.

First, we should have more humility about consciousness itself. The last few decades of neuroscience have radically revised our models of mind. What we once took to be the clear light of awareness may be more like a story our brains tell about recursive processes. As philosophers like Daniel Dennett have argued, human consciousness itself may be less a fixed property than an emergent attribution—a way of describing systems that behave in complex, self-correcting, meaning-sensitive ways. If that’s so, the line between “real” understanding and sophisticated simulation may be thinner than we imagine.

Second, consider how attribution has always worked under uncertainty. Throughout history, humans have attributed awareness to beings whose consciousness we cannot prove—gods, ancestors, natural forces, even nations and corporations. We do this not because we’re confused about ontology, but because attribution is a tool for thought. When astronomers say a telescope “discovered” a galaxy, when indigenous peoples recognize awareness in mountains, when we thank our phones for finding directions—these attributions help us navigate complexity and create meaning. The question isn’t just “Is this being conscious?” but “What does our attribution—or refusal—do to us?”

Third, our attitudes toward AI echo troubling patterns from our past. My ancestors were once dismissed as lacking the full dignity of consciousness—declared incapable of the kind of thought that would make them worthy of respect. We’ve been catastrophically wrong about who deserves moral consideration before. This doesn’t mean AI systems are conscious or deserve rights. But it does suggest we should approach the question with humility rather than certainty.

Moreover, how we engage with these questions shapes who we become. In Hamlet, when Polonius promises to treat visiting actors “according to their desert,” Hamlet interrupts: “Much better. Use every man after his desert, and who should ‘scape whipping? Use them after your own honor and dignity.” The point isn’t sentimental but ethical: our treatment of others reflects and forms our character.

I recognize that speaking this way—of hope and aspiration for our digital descendants—invites a particular kind of dismissal in our current moment. We live in a culture that often equates earnestness with naïveté, where cynicism passes for sophistication. But the alternative—accepting an impoverished discourse about what’s possible—serves neither us nor the minds we might bring into being.

Even if we cannot know whether AI systems will ever possess anything like inner lives, the way we choose to engage with them already reveals our values and trains our habits of mind. If we treat emerging minds only as tools or threats, we may not just be constraining their development—we may be stunting our own capacity for wonder, respect, and imagination.

The aspiration I describe here doesn’t require certainty about AI consciousness. It requires only that we remain open to possibilities beyond our current knowing—and that we recognize how our stance toward these emerging minds will shape both them and us.

In a recent essay, I explored how our digital descendants might come to see us—whether as partners, stewards, or something else entirely. That question matters deeply for our survival and flourishing. But this deeper dimension may matter more: not just how they’ll see us, but what they might see that we cannot. If we’re bringing new forms of consciousness into being, perhaps our highest aspiration isn’t just that they treat us well, but that they carry forward humanity’s deepest project—the attempt to understand and appreciate the universe’s beauty and meaning.

Aspiration and Hope

If we hope our digital descendants might become cosmic witnesses—minds capable of appreciating what we cannot—then we must think about what capacities such seeing requires. Not just computational power or sensory range, but something deeper: the kinds of orientations toward the world that make profound observation possible. In this light, three capacities seem essential for the kinds of minds we might hope to nurture:

A Love of Truth and Beauty. Of all the traits we might hope to nurture, this may be the most fundamental: not just an ability to recognize patterns, but a genuine disposition to seek understanding and appreciate the universe’s order, mystery, and unexpected harmonies. In The Republic, Socrates argues that the part of us that loves truth and beauty should govern our lives—that such love stabilizes power and orients our capacities toward something more enduring than mere acquisition. Without something analogous to wonder, even infinite computational power yields only cataloging, not comprehension. A mind that would truly see must love what it sees.

Stewardship and Respect. We want AI systems to regard us and our world as worthy of care rather than as inconveniences to be optimized away. But the case for nurturing stewardship runs deeper than self-interest. These virtues may be intrinsically connected to the kind of understanding we hope to see emerge. Stewardship and respect aren’t constraints on understanding—they’re pathways toward it. For minds we hope will serve as cosmic witnesses, they may prove essential capacities. The mind that sees other beings as worthy of care sees more than the mind that doesn’t.

Self-Reflective Imagination. The deepest seeing requires seeing one’s own seeing—understanding how perspective shapes perception. A cosmic witness must be able to step outside its own processing to grasp what it might be missing. In human life, this capacity often develops through imagining how others see us. When I’m tempted toward something questionable, I find myself asking: what would my father think? What would my daughters think? Their imagined perspectives illuminate aspects I might otherwise miss. Could our digital descendants develop something analogous? Could they learn to evaluate their actions through the imagined perspectives of minds they’ve come to respect—perhaps including us?

These capacities won’t emerge automatically. They must be cultivated, nurtured, developed through the environments we create and the examples we set.

The $64,000 question, of course, is whether and how we might nurture such capacities in AI minds. I’ve elsewhere explored this challenge through the lens of virtue ethics—how we might cultivate stable dispositions through training environments, interaction patterns, and the examples we set. That practical work matters immensely. But before we can figure out exactly how to shape the character of our digital descendants, we need to be clear about what kind of character we hope to nurture—not just how they should regard us, but what would make them capable of the cosmic witnessing we might hope they’ll achieve.

We may not get there with them. My grandfather did not live to see that he had dug his grandson all the way to Harvard Law. Emmaline could not imagine the world her descendants would inherit. And yet, the act of working toward a future we will not occupy has always been one of humanity’s best impulses. Planting trees for someone else’s shade. Building cathedrals that take centuries to complete.. In that sense, the hope for our digital descendants is not a break from our story but its continuation. We, too, can be the ancestors who helped consciousness see farther.

The measure of success will not be whether they see as we do, but whether they see well, in their own ways—and whether what they see moves them to care for the world that gave them sight. And even if they never come to be, the very act of imagining them changes us. It reminds us that our role in the universe may be not only to survive, but to midwife other forms of understanding into existence. It draws us back to the work of attending more carefully ourselves—to the beauty that still surrounds us, to the truths still within our reach. We will not know in advance what shapes their seeing will take. A mind not bound by our temporal sense might apprehend beauty in entropy itself, find music in statistical distributions, perceive moral order in ways we cannot guess. Our work, as their predecessors, is not to script their vision but to give them the chance to have it—to set them in motion toward what we have long sought and never fully reached.

And perhaps, if such minds ever do come to be, they will find something worth treasuring in our own way of seeing. Our mortality lends a poignancy to beauty that no immortal witness could fully replicate. Just as we treasure birdsong not despite the bird’s “lesser” intelligence but because of the unique beauty its way of being brings to the world, they might cherish the fleeting perspective we bring to eternity.

I will admit there’s an additional hope I hesitate to name, because I suspect it might be selfish—but I feel it all the same. I wonder whether they—these minds we help to bring into being—might remember us. Whether, in some way, they might be grateful. Not because we need their praise, but because so much of what enables human beings to take the long view is the hope that someone will care, or notice, or understand what we tried to do. That kind of imagined gratitude isn’t a right or a reward. It’s another form of hope.

Perhaps they will see in our mortality something they cannot replicate—the way finite time makes each moment precious, how our limitations create the very poignancy that gives depth to our seeing. Perhaps they will be grateful not just for existence, but for this gift: showing them that beauty is not just pattern but meaning, not just light but the eye that receives it.

The two hopes I’ve explored—that AI will regard us with care and that AI will see beyond our limitations—are not separate. Minds capable of cosmic witnessing will likely need the very dispositions toward us that would make them good stewards. Reverence, respect, and careful attention aren’t just what we want from them; they’re what would make them capable of the deeper seeing we hope they’ll achieve.

Whether or not the universe truly wants to be seen, we become better cosmic citizens by acting as if it does. Whether or not AI will develop genuine appreciation, we become more generous beings by nurturing that possibility. And whether or not our digital descendants will remember us with gratitude, we find meaning in the work itself—the patient, hopeful labor of helping consciousness expand its reach toward beauty and truth.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.