by TJ Price

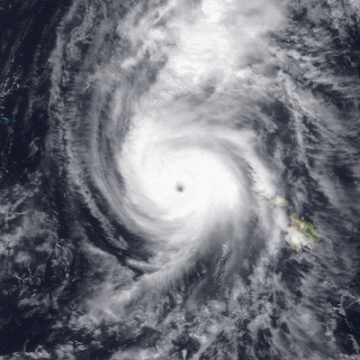

I first found the book in the used section of Longfellow Books, in Portland Maine, in the early years of the new millennium. The title included a sense of implicit dissonance, and there was no way I could resist it. It was a hardback, and the cover featured art of a book, held open to its middle pages, with the silhouette of a man and a woman cut out of it. On the dust jacket, one of the characters was described as “a meteorologist haunted by her failed predictions.”

I walked out of the bookstore into a flush of full sunlight, sat down on a bench, and began to read the novel. When I finished it, a day or so later, I closed the cover and took a breath, my head whirling with what I’d just read. A month or so later, I passed it to a friend who was looking for something good to read, and lost it for a good couple of years, as so often happens with books compulsively shared out of love.

And so: the book makes its way through our world, from reader to reader, providing the base note for a chorus of voices and developing into a rich harmony over time.

1.

I left Portland, Maine in 2017, for New York City. Long, lonely nights spent at the dim bar with too many drinks and a notebook saw me theorizing into a fog of depression: what if I just vanished, and all anyone had to go on were my notebooks? Would they be able to find me?

I’d just started trying to right my sideways-tilted life by choosing to get certified as a surgical technologist in the operating room; this took me away from the people I knew and called friends. I would get up in the pre-dawn to make my way to the hospital on the hill, then stand there gowned and gloved, intensely aware of the aseptic conditions I needed to maintain for the patient’s safety. Suddenly, with actual life and death laying insensate on the table in front of me, other things seemed less important.

When I graduated from the school of surgical technology with honors and prepared to move, I discovered that I was no longer welcome in the same circles I’d moved in for so many years. That was fine: those circles marinated in the poisonous excess of drugs and alcohol, and those friends I thought I had seemed to dissolve around me. Who would go looking for me, then, when I disappeared? I thought to myself. Did I even want them to?

2.

In New York City, I was uncomfortable. I grew up in a small, rural place, where there were acres of woods spreading out like open hands behind my house. I didn’t—and still don’t—think that density of people is meant to live in such a tiny geographical area. It seemed to me that the entire island of Manhattan must be slowly sinking due to the accumulated weight of humanity and what it wrought. I knew no one except for my husband, Matthew, who I married in a quick City Hall ceremony in early November of 2018.

I had disappeared. I changed my name, again. I cut the moorings and drifted out into the lake of the world. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

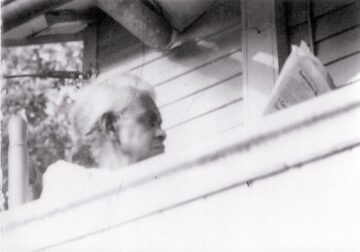

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.