by Dwight Furrow

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

But I think this way of representing wine is misleading. Wine is not a stable object to be deciphered but a field of shifting relations into which the taster steps (like Heraclitus’s river.) What if its aesthetic force lies not in measuring a wine against its ideal type but in staging tensions, oscillations, and fleeting harmonies that refuse to hold still?

The claim I will develop is that wine is not a fixed bundle of flavors but a dynamic system, always in motion, whose meaning arises through modulation—the way its elements shift and inflect one another; through differential relations—the contrasts that give each element its character; and through synthetic experience—the way these relations come together as a whole unfolding across time. To taste wine well is not to solve a puzzle, but to follow its movement as it reveals itself. Read more »

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take

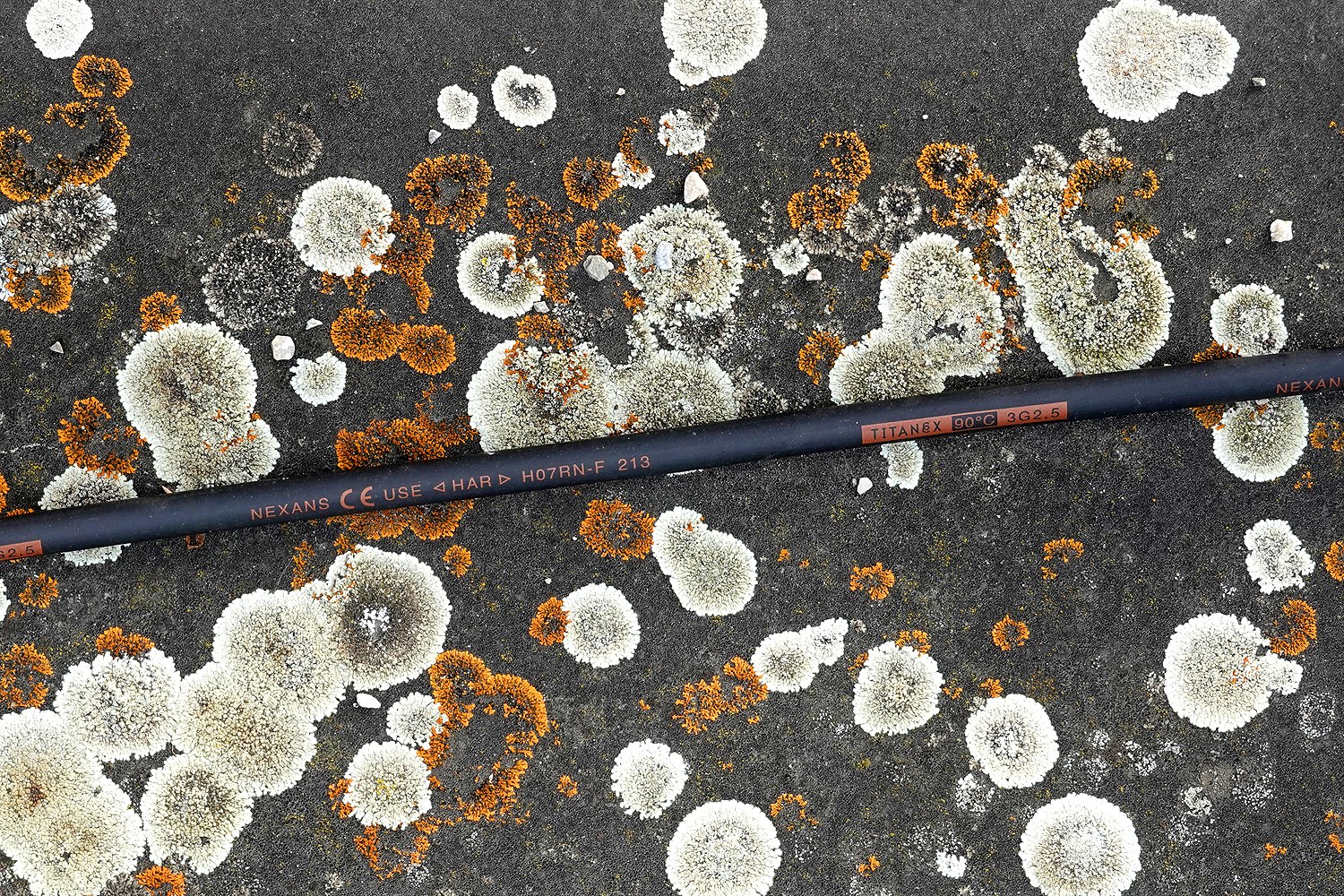

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.