by Christopher Hall

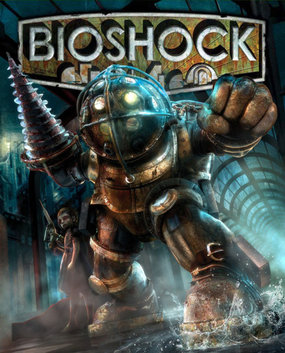

2007’s Bioshock stands as a touchstone for many on the by-now perennial, and admittedly somewhat tiresome, question of whether video games are or could be art. I remember the game for what one remembers most first-person-shooters for – the joy of slaughtering successive waves of digital monsters – but there is one moment in the game that stands out in a different way. (Spoilers ahead.)

As is typical in these sorts of games, you are given tasks, usually by a non-player character (NPC) of some sort, which you must complete in order to progress the game. The NPC – Altas – prefaces all of his requests to the player character (PC) – Jack – with the phrase “Would you kindly.” It turns out that Jack has been conditioned to do whatever he is told when a request is so phrased. In a distinctly postmodern-ish moment, the player is called upon to think of themselves in relation to the PC. They are not compelled in the same way Jack is, but absent quitting the game entirely, they have no other option but to continue. You can either do what you are assigned to do or abandon the system entirely (food for thought there). Add to this the overall setting of Bioshock: a dystopia initially created by an industrialist operating under a libertarian ideology recognisably derived from Ayn Rand. So the ultimate quest for social and economic freedom conceals instead brutal coercion. I am not silly enough to attempt a definition of aesthetic sensation, but the frisson this caused was enough to qualify in my mind.

Is Bioshock art? Could it be art? It is 20 years since Aaron Smuts asked “Are Video Games Art?” in Contemporary Aesthetics (responding to a 2000 article from Jack Kroll who firmly answered “no”), and 16 years since John Lanchester asked roughly a similar question (“Is It Art?”) in the London Review of Books. Smuts noted that there is already a tenuous distinction between art and sports:

Although we may say that a baseball pitcher has a beautiful arm or that a boxer is graceful, when judging sports like baseball, hockey, soccer, football, basketball and boxing, the competitors are not formally evaluated on aesthetic grounds. However, sports such as gymnastics, diving and ice skating are evaluated in large part by aesthetic criteria. One may manage to perform all the moves in a complicated gymnastics routine, but if it is accomplished in a feeble manner one will not get a perfect score….One might argue that such sports are so close to dance that they are plausible candidates to be called art forms.

Even if video games are essentially competitive, Smuts notes, just because that is the case does not render them “inimical” to art. If one enters a poem in a poetry contest and wins, one’s poem does not cease to be art. If Smuts is more or less successful at attacking the arguments against video games as art, Lanchester is less sure about the about their positive artistic qualities:

The medium doesn’t have, and probably never will have, a sense of character to match other forms of narrative; however much it develops, it can’t match the inwardness of the novel or the sweep of film. But it does have two great strengths. The first is visual: the best games are already beautiful, and I can see no reason why the look of video games won’t match or surpass that of cinema. The second is to do with this sense of agency, that the game offers a world in which the player is free to act and to choose. It is this which gives the best games their immense involvingness. You are in the game in a way that is curiously similar to the way you are in a novel you are reading – a way that is subtly unlike the sense of absorption in a spectacle which overtakes the viewer in cinema. The interiority of the novel isn’t there, but the sense of having passed into an imagined world is.

I am not sure I agree that there is anything inherent with this medium that would prevent it from expressing such “inwardness” or “interiority” – but I would admit that, so many years on, we aren’t there yet. Bioshock is compelling, but none of its characters come across as fully realised in the way we would expect from a novel. There is indeed no video game I’m aware of that would really compare with the experience of reading a literary novel, a great film, or even some of the better recent television shows. Lanchester is a little uncharitable when he says that video gamers “want pornography, broadly defined” – the excitement and viscerality of extreme and, it must be said, usually violent experiences. Agency and visual splendor still give way to the pleasures of being able to shoot people and cause mayhem without consequence. Is that visceral nature an essential component to these games, and if it is, is it going to press forward so firmly that any artfulness is shunted to the background?

Another take comes from film critic Roger Ebert. He is responding to a video in which the presenter argues for video games as art, and is firm about the division:

One obvious difference between art and games is that you can win a game. It has rules, points, objectives, and an outcome. Santiago might cite a [sic] immersive game without points or rules, but I would say then it ceases to be a game and becomes a representation of a story, a novel, a play, dance, a film. Those are things you cannot win; you can only experience them.

This unsubtle statement is perhaps a better starting point for us, as it is not hard to find that Ebert is almost entirely wrong about the nature of a great many video games; they may involve “winning,” but winning is not necessarily at the core of the experience. The word “game” now becomes a bit of a distracting category error in relation to the discussion. One does not “win” Bioshock – one finishes it, and even if the narrative and characters are a little undercooked, we are “finishing” a “reading” of them in a way that is not terribly different from the way one finishes a novel. Yes, as is typical in such things, there is an “end boss” which you must defeat to complete the game. But the game is also a narrative, and that narrative comes to a conclusion (actually, two possible conclusions, depending on the moral choices one has made over the course of the game). Bioshock and games like it are in fact narratives with an assortment of mini-games within them. Let’s say a novel had a puzzle in the middle of it; if it had a story, and concluded that story one way or the other, would the existence of the game within it invalidate the work as a novel? At every moment we want the distinction between games and art to hold, we find ourselves awash in counterexamples. Even if we risk stretching the definition of “language games” a little too far, the existence of novels like Pale Fire, Hopscotch and Landscape Painted with Tea at least indicates the firm delineation Ebert sees doesn’t actually exist.

Even if it is true enough that a great many video games consist of nothing but “rules,” “points” and “objectives” – I’m not sure why Ebert thinks having an “outcome” is disallowed for art – as long as we are focused on a zero-sum, win-lose outcome as ontologically determinative for video games, we will leave much important out of our definition. Narrative structure in many games is not merely a way to give some rationale to the pervasive violence. 2014’s survival game This War of Mine provides another illustration. Survival games as a genre are not particularly intricate; one is placed in an inhospitable landscape, made to craft the tools needed for one’ survival, and then – this won’t be surprising – encouraged to pummel threatening monsters and, indeed, one’s fellow survivors. The setting for This War of Mine is a city besieged, and the inspiration here clearly comes from the real-life Siege of Sarajevo. Over the course of the game, one must scavenge for meager resources, build one’s ultimately inadequate shelter, avoid confrontations with other survivors and, of course, stay alive. The game ends at an arbitrary point when a ceasefire is declared; if you’re alive, you’ve “won” the game. At this point speaking in terms of “winning” seems cruelly ironic, but of course, there is a cruel logic in the mechanics of game theory when one is put into a situation where one’s survival may inevitably be to the detriment of someone else’s. “Winning” and “losing” achieve a status here which are both inextricable from the nature of games themselves and brutally significant. You don’t win This War of Mine; you finish it, you get to go on.

So, we can finish games; outside of poetry contests and the like, is there any sense to talking about winning and losing in relation to art? We talk casually about “wins” in relation to some difficulty overcome. It may indeed be a “win” to finish a particularly difficult novel or perceive something new about some piece of art – but despite the not-inconsequential matter of the cultural capital so gained, it may be perverse to talk about this in terms of a game won. Yes, getting through Infinite Jest is a victory, but we’re likely not at the point where we can say we’ve “won” the novel by doing so. Let’s take this from a different angle. As noted, not every aspect of art needs to fit tightly under the “art” rubric; there may be any number of moments which taken in isolation would be extraneous to that. Even the most recondite piece of literary art might have someone asking for a cup of tea or where the cat is. A whole-part discussion need not distract us here, and it may that in well-wrought works everything is subsumed into the ontic frame of art. But whatever we think of rule-determined and objective-oriented things like games, there seems little reason to suppose that their mere participation is somehow anathema to the aesthetic. However loosely or tightly we take their definitions, winning and losing are such pervasive human experiences that it’s perhaps a little surprising that anyone thinks games can’t be art merely on that basis.

If there may not be the video game equivalent of Moby-Dick out there waiting to be played, present examples ought not to bar future possibilities, and it may take longer than we anticipate for the real potentialities to emerge. If one could scoff at the potential for television in the era of Hee Haw, things seem less clear, decades on, in the era of The Wire and Breaking Bad. As the considerations on the nature and cultural significance of video games has burgeoned over the last 20 years (and ludology is of course an established discipline) it’s become evident to me that so much here is ripe for aesthetic exploitation. If a real ludo-aesthetics is going to emerge, it will of necessity consider the expanding possibilities for form and content. Branching and emergent narratives and the capacity for audience choice in these are only the beginning. As Smuts and Lanchester intimate, video games are a kinesthetic performance, and while we are used to being an audience for such events if we are watching dance or a play, the idea of audience participation seems an exciting possible frontier. Indeed, if anything distinct emerges about video game art, it will likely be contained in this element of audience participation; “viewer/reader” and “text” may need to undergo revision as distinct entities.

But the basic creative impetus here is more basic: tell a true creator they are barred from creating something in this way or in that medium and they will do everything in their power to prove you wrong. The results may vary, and not every experimentation is a success. The big barrier here may be one familiar to filmmakers; video games are tremendously expensive to make, so the pressure inherent to creation under the aegis of capitalism must be more acutely felt here than where a poet creates a poem. But great films continue to be made, their aesthetic status not in doubt, but more importantly, film as a medium has developed its own modes of intricate expression that simply didn’t exist before, and took time to develop. So one imagines a game: you may play one of two characters, the hunter or the whale. Either way, you are bound to traverse a great watery landscape, both seeking and sought, undertaking the exploration of connection and disjunction between you and your enemy that may or may not lead to disaster, depending on your choices and skill. Win or lose the story, finish the game, we will know in the moment of recognition what we are truly encountering.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.