by Derek Neal

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

As far as I can tell, most writing about music is built on analogies and cliches. This is understandable; you can’t describe music literally because it wouldn’t give an accurate representation of what it is you’re hearing. What use is it to say that a song is written in the key of A minor, has a tempo of 110 beats per minute, and follows a 4/4 time signature? These facts don’t add up to much. On the other hand, using analogies to describe music is meant, I suppose, not to state the objective facts of a song but to capture the experience of listening to a song and the subjective emotional response created within the listener. Perhaps, in combining technical, factual description of a song with figurative language, a song can be captured via text and the reader can hear the song in their head without ever actually having heard it out loud. This seems to be the goal of most music reviews.

I was put in mind of all this when I read an article in this month’s issue of Harper’s about the transition from the pre-internet world to the digital world of today. The author, Hari Kunzru, was writing about how he would read descriptions of music in magazines and try to imagine what the music sounded like, which does bring up the question: when we can listen to any song instantly, is it even necessary to attempt to put music into words? Perhaps the genre of the music review is simply a historical anomaly that has run its course. This may be true, but the same could be said and has been said for the novel, the essay, and many other forms of traditional composition. And yet here I am, writing these words, so I’ll continue to explore the description of music and attempt to achieve its goal of transmitting sound via written language. Read more »

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed. The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

Early in the story of

Early in the story of

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows.

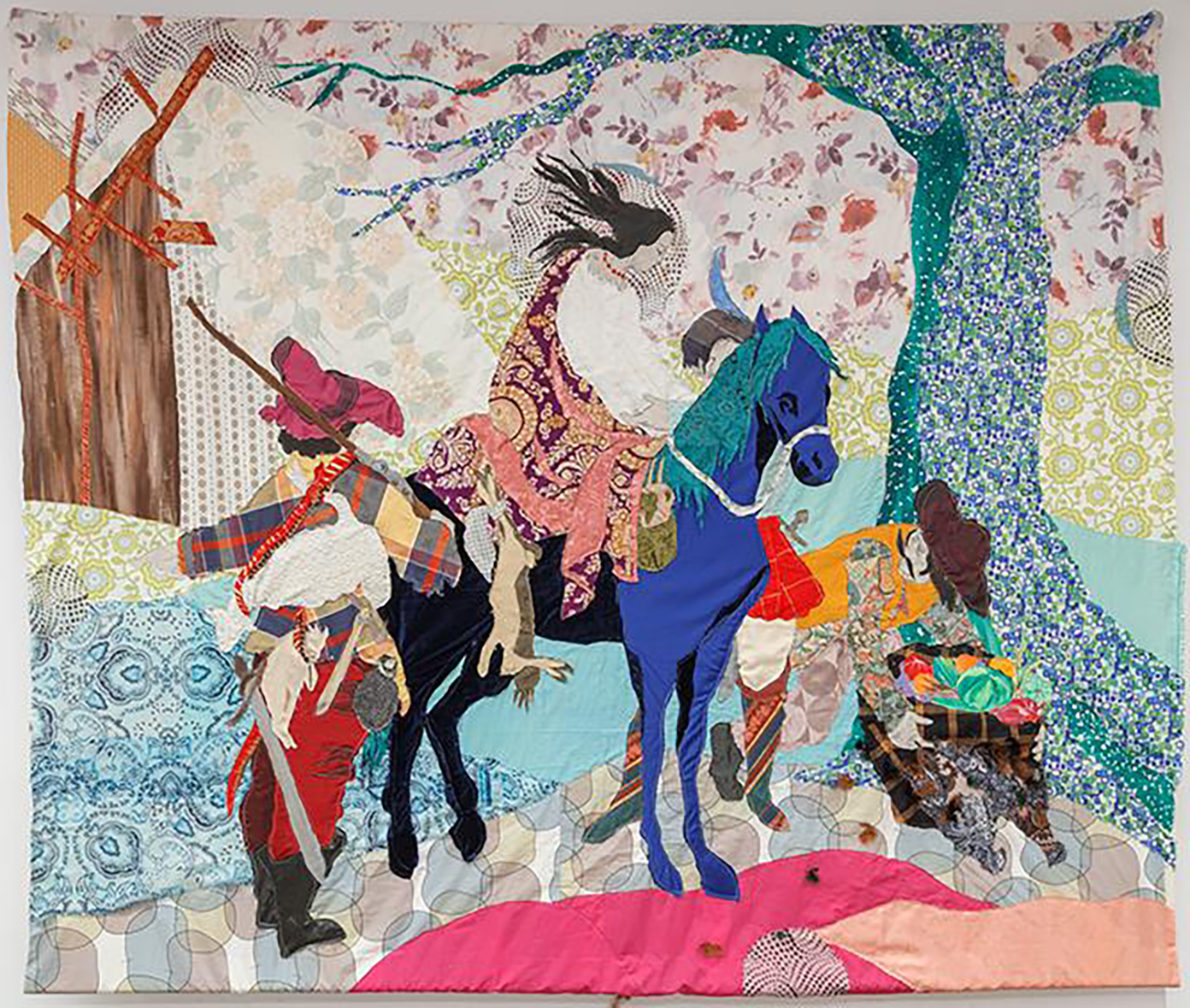

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021 Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.

Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.